Walking to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease

The Power of Walking: A Simple Step Towards Preventing Cardiovascular Disease

In the quest for a healthy heart, it’s easy to overlook the power of one of the simplest and most accessible forms of physical activity: walking. There is tremendous potential for walking to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD), which remains a leading cause of death worldwide.1,2 Research highlights the benefits of walking in reducing the risk of heart-related ailments.3–5 By incorporating this low-impact activity into our daily routine, we can take significant steps towards maintaining a healthy heart and preventing the onset of CVD.

The Impact of Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease, encompassing conditions such as heart attacks, strokes, and coronary artery disease, is not only a national concern but also a global health concern. According to the World Health Organization,6 CVD is the leading cause of death worldwide. The prevalence of CVD can be attributed to various modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors.

Examples of modifiable risk factors include:7

- High blood pressure

- Elevated cholesterol levels

- Obesity

- Smoking

- Sedentary lifestyle

Examples of non-modifiable risk factors include:8

- Family history of CVD

- Age

- Gender

- Ethnicity

Fortunately, there are health promotion behaviors we can enforce, (e.g., engaging in regular physical activity through walking) to mitigate these risk factors and significantly reduce the incidence of CVD.

The Cardiovascular Benefits of Walking

Brisk walking, a typically moderate-intensity form of physical activity, offers numerous benefits for cardiovascular health. Our heart is a muscle in which the primary function is to circulate blood throughout our body.9,10 Like any other muscle in our body, it is important to maintain the heart’s strength to ensure it functions properly. Increasing our heart rate, through walking, helps to strengthen our heart muscle.11

Additionally, walking can be an effective strategy in lowering blood pressure, reducing LDL cholesterol levels, improving insulin sensitivity, and reducing or maintaining healthy weight, which are all crucial to reduce the risk of heart disease.12,13

Murtagh et al14 carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials to investigate the effect of walking on CVD risk variables. Walking improved various CVD risk variables, according to the study. Blood pressure, weight, body fat, and BMI are among the risk factors indicated. Lipids did not fare well in the study.

Paula et al.15 carried out a 4-week randomized controlled trial to determine how the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and walking impacted patients with type 2 diabetes and uncontrolled high blood pressure. The intervention group was advised to increase their walking to at least 15-20 minutes a day, 5 days a week, and the control group maintained their usual physical activity. Additionally, the intervention group followed the DASH diet while the control group received dietary recommendations. The researchers discovered that participants in the intervention group had lower blood pressure.

Accessibility and Convenience

One of the greatest advantages of walking is its accessibility and convenience. Walking requires no special equipment or expensive gym memberships and can be done almost anywhere and at any time. A brisk walk around the neighborhood, taking the stairs instead of the elevator, or incorporating short walks during work breaks, all provide positive impacts.

With walking, there are no limitations in terms of age or fitness level, making it an ideal choice for individuals of all backgrounds and abilities. In elementary children, a 5-week walking program contributed to a decrease in being sedentary and a decrease in disruptive class behavior.16 A secondary data analysis that focused on older adults and the impact of walking on mental health and health perception, showed higher health perceptions and mental health in older adults who participated in moderate-intensity leisure walking compared with light-intensity leisure walking.17

Tips for Creating a Walking Routine

With any form of physical activity, consistency is important to benefit from an individual’s chosen form of physical activity. According to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans,18 it is recommended that adults do at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity physical activity. Children, starting at age 6, and adolescents, should do at least 60 minutes daily, and older adults or adults with chronic health conditions or disabilities should do at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity physical activity, if able.

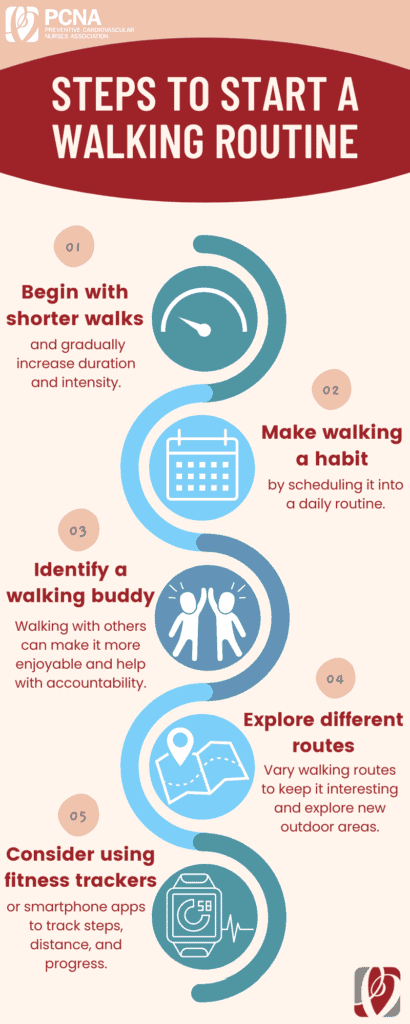

There are several strategies an individual can utilize to start a walking routine and build their routine to meet the recommended amount of physical activity.

Clinical Implications for Nurses

Nurses of varying professional roles are equipped to provide the foundation for engagement in physical activity. Nurse practitioners have the capacity to prescribe walking as part of a patient’s treatment regimen. The nurse practitioner must consider, however, the walking environment of the patient as their environment can impact their engagement in physical activity. Nurses are equipped to educate patients and reinforce the importance of physical activity. There is also an opportunity for collaboration among nurse researchers, other healthcare professionals, community stakeholders, and community members to conduct research on walking interventions to prevent CVD.

Related Resources

- Heart Healthy Toolbox – Lifestyle and behavior change tools, including motivational interviewing and exercise tools

- Ideal Exercise Prescription for Cardiovascular Health

- Physical Activity, Exercise Training and Heart Failure: Does Intensity Matter?

References

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145(8):e153-e639. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052

- Shiels MS, Haque AT, Berrington de González A, Freedman ND. Leading causes of death in the US during the COVID-19 Pandemic, March 2020 to October 2021. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(8):883-886. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.2476

- Saint-Maurice PF, Troiano RP, Bassett DR Jr, et al. Association of daily step count and step intensity with mortality among US adults. JAMA. 2020;323(12):1151-1160. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1382

- Omura JD. Walking as an opportunity for cardiovascular disease prevention. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16. doi:10.5888/pcd16.180690

- Duran AT, Friel CP, Serafini MA, Ensari I, Cheung YK, Diaz KM. Breaking Up prolonged sitting to improve cardiometabolic risk: Dose–response analysis of a randomized crossover trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2023;55(5):847. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000003109

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases. Accessed July 5, 2023.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Heart-healthy living – understand your risk for heart disease. Published March 24, 2022. Accessed July 5, 2023.

- Brown JC, Gerhardt TE, Kwon E. Risk Factors for Coronary Artery Disease. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Accessed July 14, 2023.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. Anatomy and function of the heart’s electrical system. Published August 8, 2021. Accessed July 14, 2023.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. How the heart works – the heart. Published March 24, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2023.

- John Hopkins Medicine. 3 kinds of exercise that boost heart health. Published November 3, 2021. Accessed July 14, 2023.

- Harvard T.N. Chan. Walking for exercise. Published December 9, 2020. Accessed July 25, 2023.

- American Heart Association. Walking your way to better health? Remember the acronym FIT. www.heart.org. Accessed July 25, 2023.

- Murtagh EM, Nichols L, Mohammed MA, Holder R, Nevill AM, Murphy MH. The effect of walking on risk factors for cardiovascular disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised control trials. Prev Med. 2015;72:34-43. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.041

- Paula TP, Viana LV, Neto ATZ, Leitão CB, Gross JL, Azevedo MJ. Effects of the DASH diet and walking on blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes and uncontrolled hypertension: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Hypertens. 2015;17(11):895-901. doi:10.1111/jch.12597

- Jenny S, Almond E, Chung J, Rademaker S. Sport management majors’ perceived motivators and barriers to participation in a college-sponsored international experience. Phys Educ. 2019;76:547-567. doi:10.18666/TPE-2019-V76-I2-8255

- Han A, Kim J, Kim J. A study of leisure walking intensity levels on mental health and health perception of older adults. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2021;7:2333721421999316. doi:10.1177/2333721421999316

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition.