Health equity issues, including access to medications, significantly impact patients with heart failure. From pharmacy deserts to non-medical switching and beyond, hear strategies to assist patients in getting the medications they need, from nurses Binu Koirala, PhD, MGS, RN, with the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing in Baltimore, and Kim Newlin, MSN, ANP, FPCNA, of Sutter Roseville Medical Center in Northern California.

Earn 0.5 contact hours and .05 pharmacology hours from listening to the podcast episode and completing the course components.

This podcast is supported by independent educational grants from Merck Sharpe and Dohme Co and the Pfizer-Merck Alliance.

Episode Resources

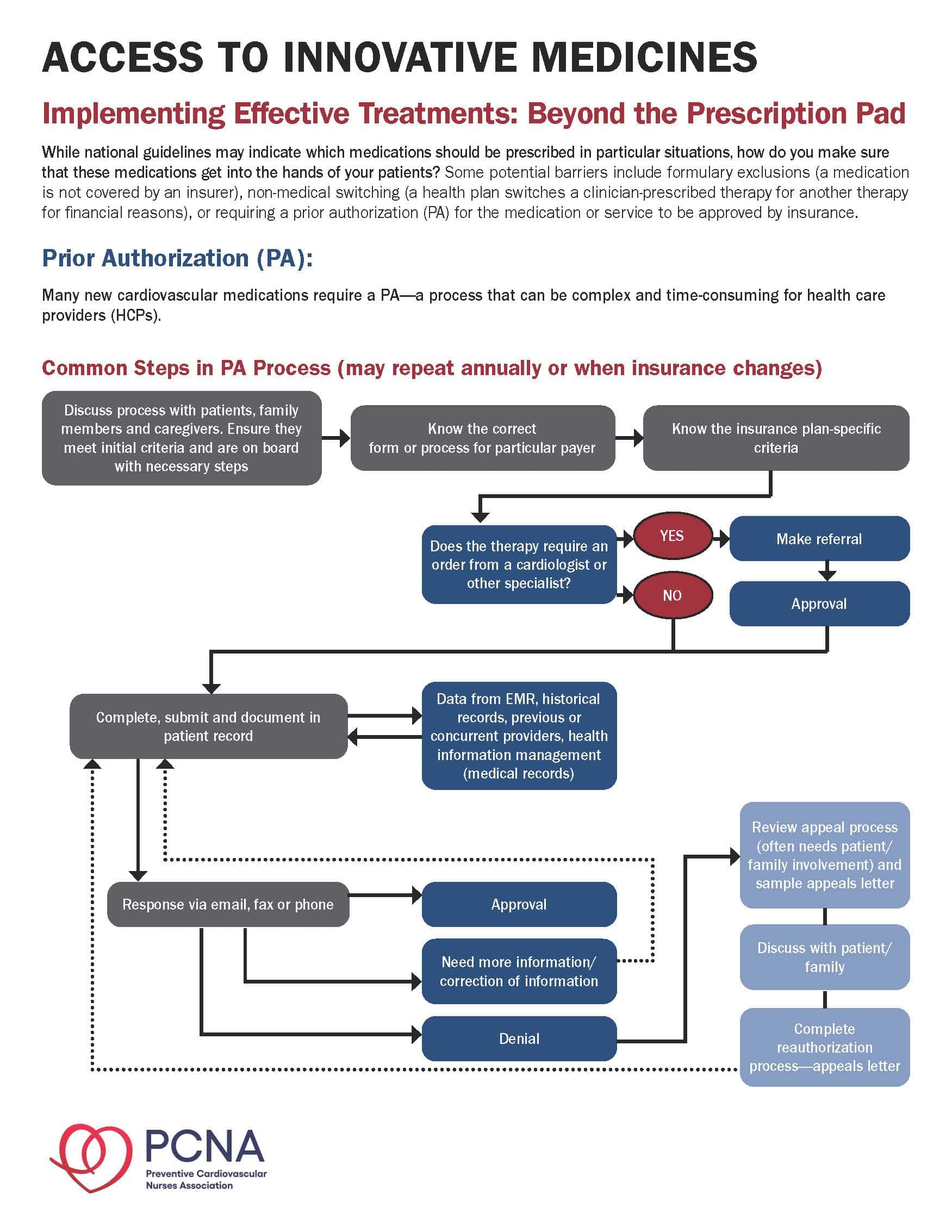

- Provider tools: Access to Innovative Medicines

- Medicare State Pharmaceutical Assistance Program

- Extra Help with Medicare Prescription Drug Care Costs

- CoverMyMeds

- Solving medication access issues from the American College of Cardiology

- Non-Medical Switching of Medications

- CDC on Health Equity

- Understanding Copay Accumulators

- Partnership to Advance Cardiovascular Health (PACH)

Welcome to Heart to Heart Nurses, brought to you by the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. PCNA’s mission is to promote nurses as leaders in cardiovascular disease prevention and management.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Welcome to today’s episode where we will be discussing the intersection of health equity and heart failure. I’m your host, Geralyn Warfield.

This episode is available for CE contact hours. Please be sure to follow the link in the episode show notes, to complete the post-test and access your CE certificate.

Today, we’re so pleased to be able to be joined by Binu Koirala and Kim Newlin. Binu, could you introduce yourself and then we’ll have Kim do the same?

Binu Koirala (guest): Sure. Hi everyone. Thank you for having us. I’m Binu Koirala. I’m an Assistant Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. My clinical and research [00:01:00] background and focus include cardiovascular disease prevention and management, palliative care, and care of patients living with multiple chronic and complex disease conditions, including heart failure. And I’m really looking forward to our conversation today as it is a really important topic.

Kim Newlin (guest): And this is Kim Newlin. I come to you from the other side of the United States. I am an Adult Nurse Practitioner and Cardiovascular Clinical Nurse Specialist. I’m also a Director of Nursing at Sutter Roseville Medical Center in Northern California.

At the hospital, I have oversight over our cardiac rehab program and I see high-risk heart failure and post-myocardial infarction patients in our heart health clinic after they are discharged from the hospital. It is truly an honor to be here. This is something I work on every day in our transitional clinic, so thank you for having both me and Binu.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Well, we are really grateful to you for sharing your time today. And why don’t we go ahead and dive in. Our [00:02:00] listeners, I’m sure, can likely describe a number of ways that the issue of health equity affects our patients, particularly our patients with heart failure. And just to make sure that we’re all using the same terms in the exact same way, could you please describe for us what we mean by health equity? Kim, could you start?

Kim Newlin (guest): Yes, absolutely. And I think, I think we’re really fortunate nowadays to have this as part, a lot more conversation, it’s embedded in the research we do, and we all have training on this. But I, I think there’s a great definition that I like to use. And it’s one that the CDC gives and I’m just going to read it because I, I probably would butcher it if I didn’t do, if I tried to paraphrase it. But ‘Health equity is achieved when every person has the opportunity to attain his or her full health potential. And no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or other socially determined circumstances.’

You know, it’s really [00:03:00] proven that health inequities are reflected in differences in, in everything that we see. So length of life, quality of life, rates of disease, disability, and death, severity of disease, access to treatment. So again, I think that’s a good overall definition, but I’m going to pass it to Binu, too, who can talk a little bit more about health equity.

Binu Koirala (guest): That’s a great definition, Kim and I, I love that definition too. And when we are talking about health equity and heart failure, I think we also need to talk about social determinants of health and its effect in the prevention and management of heart failure. And through our research work and, like in, it has been extensively documented that Blacks have a higher incidence of heart failure and they disproportionately have worse heart failure-related health outcomes when compared to whites.

So, although [00:04:00] evidence highlights that there is racial and ethnic disparities in heart failure outcomes, often these outcomes among racial and ethnic subgroups are confounded by various underlying social cultural factors such as low education, lower health literacy, lower socioeconomic status, as well as the limited access to quality of care.

So, and in addition to that, like, there are other factors such as inadequate housing, food insecurity that has existed in our community, and living conditions. All these are associated with worse heart failure and chronic disease outcomes. So, what I think is, when we talk about health equity, I think social determinants of health and access to care comes together.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Thank you both for getting us started on the right track as we’re talking about health equity issues with our patients with heart failure. And perhaps [00:05:00] let’s focus just a little bit more on how access to care can impact our patients with heart failure. Binu, could you please start?

Binu Koirala (guest): Sure. So, there are many pieces when we are talking about addressing or managing heart failure, and which depends on the access to healthcare. So, access could mean, like mean many things, from having sufficient health literacy to understand the disease and treatment that is required to help prevent symptoms, exacerbations, and hospitalizations.

Also, access could mean access to finances, to, to pay for medications and visit to the clinic. Specifically, if our patients don’t have access to healthcare insurance, they may not be able to afford their hospital stay. Also, they cannot afford the visits, and the follow-up medications. So, they [00:06:00] may end up using their essential funds that they pay for their regular life—their bills, their healthy food, and transportations.

So, access is really, really important. And talking about access, like access to healthy food, is also important in heart failure. And we still see many problems with access to transportation, and the issue of food deserts—that is an area where there is limited access to affordable and nutritious food.So, you know, to achieve health equity we also need to impress this on providing, like, addressing the social determinants of health, and not only the medical care. And it’s challenging.

And I just want to highlight one program that aimed at addressing health disparities, by considering access to care and health equity, and which has been implemented by the [00:07:00] Grady Health System in Atlanta.

So this Grady heart failure program is a unique and innovative program, which consists of multidisciplinary team members. And their goal is to promote health equity by improving access and quality of care among the heart failure patients. And, you know, the main components, or the beauty of the program that I really liked about when I knew about this program was they have hospital-based financial assistance.

They also provide a 30-day supply of heart failure medication at the time of hospital discharge. They connect their patients to community resources via dedicated community health workers. They have provision for medically tailored meals post-discharge, as well as they provide ride share support who does not have transportation [00:08:00] means for the follow-up appointments. And, also, they provide mobile health home visits. If patients have mobility problems or caregiver responsibility, and they cannot leave their residence.

So, this is just a one example, and I know Kim is involved in a similar program at her place. Kim, do you mind saying more about that?

Kim Newlin (guest): Oh, not, not at all. And I, I don’t even know if I could say I’m in the same league as Grady. And I, I think this is such an important program, and I love learning about new programs, because it really challenges me to look at how I’m really ensuring that I’m addressing some of these barriers.

So just so you guys know, there’s actually a toolkit that Grady created in partnership with the CDC around their model, which gives a lot of really good information. So, the, I’ve run at this clinic since 2011 and we actually closed down during COVID. [00:09:00] which was not ideal. But we have had graduate students come through and worked on projects, addressing health literacy, transportation, dental care, food deserts, just on such a small scale compared to what Grady did. But I think, again, reading about it and hearing about it, it’s one of those programs that really pushes you to do better.

And now with reopening the clinic again, we actually have some, some support tools within Epic now that address social determinants of health. So, our, our electronic health record allows us to actually pull those into our record and really look at those, and, and see how we’re doing or how we’re not doing in addressing some of these things that really impact our patient’s ability to get the care that they need.

Another way that access or another program that access can be addressed by is through telehealth. Okay. So, during the last couple of years with the COVID pandemic, we have really [00:10:00] been fortunate, actually, to push forward the telehealth agenda. So, both virtual visits and telephone visits to allow us to really access patients who are either in rural settings, or it’s just difficult for them to get into the clinic for visits.

So, we know that using telehealth interventions can increase convenience of care which is, is pretty obvious. It’s, increases the efficiency—so both cost and volume. So, the number of patients you can see if you’re not having to room them and, and have them come in and out of the room and clean the room, it allows for more continuity of care. So, whether it’s used as a supplement to inpatient visits with our heart failure patients who need often touchpoints more frequently, that can be provided and often by the same clinician. And just the experience of receiving that care.

So for providers, we know that telehealth enables them to offer both [00:11:00] timely healthcare services to hard to reach areas. And as long as we’re making sure we address those technology issues that patients may be experiencing.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Thank you both so very much. Binu, you had described a little bit about food deserts and folks not having access to healthy foods near their home or their place of residence. And I’m wondering how that might apply to pharmacy deserts. Kim, maybe you could address that for us.

Kim Newlin (guest): Yeah, absolutely. So, like you said, pharmacy deserts are, are similar to food deserts and thank you, Binu, for bringing up that important concept. So, the definition of a, of a pharmacy desert is where a low-income neighborhood has either an average distance to the nearest pharmacy that’s greater than a mile, or whose average distance to the nearest pharmacy was greater than half a mile but at least a hundred households had to, had no vehicle [00:12:00] access. So, kind of two different definitions, but same concept, right? Where you don’t have a pharmacy nearby to pick up these needed medications or get other treatment that pharmacies are, are now providing.

So, there’s some actually good research and we’ll make sure that these, these references are put into the notes here for this podcast. But once, some studies have shown that one in three neighborhoods throughout the 30 largest cities in the U.S. actually are pharmacy deserts. And this, again, during COVID was really highlighted where the few pharmacies that often served segregated Black and Latinx neighborhoods were less likely to offer very important immunizations, didn’t have 24-hour availability for people working different shifts or just needing flexibility. Drive-through services were often not provided either, so people had to get out of their cars and go in which many people were afraid to do, and, therefore, were [00:13:00] not, were not going to pharmacies if they didn’t have that drive-through service.

What we also saw is that these areas were more likely to close permanently. And when you have pharmacies close, you have lower adherence to medications, prevent heart attacks and strokes. And it also more likely aggravated disparities in the COVID-19 testing and vaccinations. So, you know, some important information or just kind of ideas around how we can make sure that these pharmacies can stay open, is really trying to address that root cause, right? So often it’s low reimbursement rates. So those independent pharmacies or those pharmacies that are willing and able to stay open in these, these lower socioeconomic neighborhoods, they need to be reimbursed by Medicare and that Medicare reimbursement can really help them stay open and, and help address medication, access [00:14:00] issues, vaccinations, and other healthcare that’s now being provided in, in many pharmacies.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Binu and Kim, you have given us so much to think about already. Things that are affecting our heart failure patients beyond what we’re considering when it comes to treatments and therapies, but just access to so many different things and how health equity can have a significant impact on these patients.

We’re going to take a quick break and we’ll be right back.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We are back speaking with Kim Newlin and Binu Koirala about the intersection of health equity and heart failure. And I’d like us to address another series of issues that affects our patients. And that i, the issue of access when it comes to non-medical switching and payment accumulators. I’m wondering if you could take turns describing that for us. Maybe Kim, you could start?

Kim Newlin (guest): Absolutely. Absolutely. So, this term non-medical switching, I would say, I probably learned about it [00:15:00] maybe four, four or five years ago. And I, it was, it was something that was very shocking to me. I think I didn’t totally understand conceptually what it meant.

But what it means, or what it refers to, is when a person who may be on a stable medication, let’s say an ACE inhibitor like lisinopril, is switched for non-medical reasons. So, they’re switched to another ACE inhibitor, like Prinivil, or an APRI, right? So, something that is maybe just new to the patient. And it’s not because of an allergy or it’s not because of any other reason, but maybe because the patient’s insurance plan doesn’t cover it or there’s a less expensive, but technically therapeutically, therapeutically equivalent drug.

So, I actually remember when this happened to one of my first patients and they had been on a certain ACE inhibitor for years and years, and they got [00:16:00] switched and they were not informed, and they went and picked it up and it was a different color and a different shape. And they went to take it and they actually had a pretty significant allergic reaction. And it was probably something in the compounding of that medication. But again, that patient had been really stable and then became extremely gun shy about taking this medication because of those adverse reactions that they had.

So, again, there’s, we’ll put this in the notes, but there was a, a great analysis done in 2016 with looking at about 30 scientific studies that looked at non-medical switching and over 250,000 patients. And what they identified was that non-medical switching ended up leading to either negative clinical or economic outcomes, or maybe neutral clinical or economic outcomes, but no, with no positive outcomes. So, what they were intending to do was at least have an economic benefit, but that actually wasn’t even [00:17:00] realized in this analysis.

And this was really true for patients with chronic diseases who are medically stable before the medication switch occurred, and those who then stop taking medications because of this switching, ultimately end, ended up having either disease progression, they had more hospital visits, more doctor visits, more emergency room visits—so, everything we’re trying to do with preventive care is prevent all of those. And then, ultimately, leading to higher healthcare system costs. So, through this attempt to reduce costs for, possibly the health plan, what we’re seeing is more expensive total cost of care, which is not the goal of, of the U.S. healthcare system at this point.

Geralyn Warfield (host): That’s incredible information, Kim, and lots of food for thought there. Binu, I’m hoping you can help expand our knowledge just a little bit more and talk about copay accumulators.

Binu Koirala (guest): [00:18:00] Sure. And Kim, like when I heard this term ‘copay accumulators,’ I had the same situation. Like it took me some time to read about it and know more about it, like how it works and what’s the right mechanism, and how it affects our patients as well as the providers.

So, to start with, copay accumulators, also known as an accumulator adjustment program, is a strategy used by insurance companies, and the pharmacy benefit managers, that restrict the use of manufacturer copay assistance coupons from counting towards the deductible, and the maximum out-of-pocket spending.

So how it works is, so for many chronic conditions, we have to treat patients with drugs that are made from living cells or which are like really costly. And as drug manufacturers, they attempt to [00:19:00] create programs, or offer copay assistance, to subsidize the out-of-pocket cost for the patients. And the insurance companies and the pharmacy benefit managers reduce the value of these programs by adjusting such funds while also requiring patients to pay their deductibles and co-insurance up to their out-of-pockets to obtain their medications before the actual plan benefits kick in.

So with this, we have seen, many patients have caused challenges when they are living with chronic conditions and they are more likely to fall under financial hardship and which, in turn, can lead to like increase our likelihood of treatment nonadherence and can also lead to an advanced disease state.

So, what is the implication for the providers? So, I believe this adds the [00:20:00] responsibility for the providers or clinicians office to make sure that they investigate patients plan thoroughly when, when they do the benefit investigation process, and to help identify the plans that include an accumulator adjustment program, anticipate and prepare for an increase of copay accumulator plans, and also provide education to the patients and counsel their patients on their benefits for a specialty drug and how their financial obligation can be impacted during their therapy journey.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We certainly have covered a lot of ground today, and I’m hoping you might have some suggestions of resources for our listeners who are interested in learning more about any of these topics. I’m not sure who would like to start, but please share whatever resources you might have so that our clinicians will have that information available for themselves and their patients.

Kim Newlin (guest): [00:21:00] Yeah, this is, this is Kim. I’m, I’m happy to start here. And I think both Binu and I have expressed some of our kind of surprise in learning some of these things. And, and many of you who are listening have probably experienced it, in a way where a patient comes back to you and can’t understand why in February they’re paying a certain amount, but in November they were paying something different.

And it’s when either their pharmacy benefit manager switches or, you know, something happens with their insurance and the contracting. So it’s, it is a whole field. It could probably be a whole major or subspecialty of nursing to learn. And I think a lot of us are impacted and are having to deal with this on a daily basis.

You know, I’ve had friends say, gosh, I didn’t go into nursing to be the prior authorization queen, but I think I, I do have a couple of places that I go. One is when I’m prescribing a new medication that is, where there’s not a [00:22:00] generic form, I really try to make sure I’m looking on the website for any pharmaceutical company to see what’s out there.

So yes, there are copay cards which with those copay accumulators has the, the landscape’s changed a bit, but still those, a lot of those pharmaceutical companies have patient assistance programs, which will help. And they have experts who can really help those patients navigate cost and help them understand, with their current insurance, what the cost is going to be. So, they go in informed.

I also have found that there are some programs such as CoverMyMeds; Extra Help, which is part of the Social Security Administration, which can help also get patients coverage; and we, you know, we try to put together a binder to have that information because it, it does take a fair amount of time, and things change as well.

I’m also going to refer you guys to two websites that I strongly recommend you visit. One is [00:23:00] actually the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association site, for Access to Innovative Medicine provider tools. So, this site actually has six great tools for navigating prior authorizations, helping patients get the medications they need and, and real-life tips from nurses. So, if you feel like your hands are tied, or you’re not getting what you need, or you’re not even sure where to start, you can find a lot of great informational nuggets here.

The other site I recommend you go to is, if you’re interested in helping out on a larger scale, the Partnership for Advancing Cardiovascular Health website, or PACH. And this, this group’s mission is to work on advancing public policies and practices to help reduce barriers and improve kind of access to these innovative medications. So, they talk about this non-medical switching, and they talk about just the, the steps for prior authorization. So, they work at a state level and a national level to [00:24:00] help, help provide education about what’s happening, what are pharmacy benefit managers. That could be its own whole podcast, I’m sure.

But those two sites are, are super valuable and I find myself going to those just to learn myself and then also see what else is being done again, locally and at a national level.

Binu Koirala (guest): Great resources, Kim, and to our listeners, we will make sure to add these resources and others in the episode show notes, so you can refer to them any time you want.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Thank you so much, Binu, thank you so much, Kim, for sharing your expertise for sharing resources, for sharing the journey that our patients with heart failure are on that go beyond clinic visits and, you know, just listening to what the medications are supposed to do to so many other factors that affect their health. Health equity and heart failure, like all clinicians recognize, are closely intertwined, and we hope that our listeners have [00:25:00] come away with some great nuggets of information that they can apply right away.

This podcast is supported by independent educational grants from Merck Sharpe Dohme Corporation, and the Pfizer-Merck Alliance.

And this episode, as I said before, is available for CE contact hours. Make sure that you follow the link in the episode show notes, to complete the post-test and access your CE certificate. This is your host Geralyn Warfield, and we will see you next time.

Thank you for listening to Heart to Heart Nurses. We invite you to visit pcna.net for clinical resources, continuing education, and much more.

Topics

- Health Equity

- Heart Failure

Published on

September 20, 2022

Listen on:

PhD, MGS, RN

ANP-C, CNS, RN, FPCNA

Related Resources