What is AFib?

Globally, atrial fibrillation (AFib) continues to increase in prevalence as the population ages. In the US alone, an estimated 10.5 million individuals are affected—1 in every 22 people.1 The lifetime risk is about 1 in 3 white individuals > age of 45,2 1 in 5 African Americans ≥ age 40,3 and 1 in 10 Chinese individuals ≥ age 40.4

Early detection of AFib and implementation of guideline-directed treatment strategies can reduce the frequency of AFib-related complications. AFib can lead to blood clots, stroke, and heart failure, and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. AFib not only affects individuals, families, and communities, but also is a significant cost to healthcare systems; the mean total healthcare cost for a patient with AFib was an estimated $27,896 more per year than for a patient without AFib.5

What is the AFib Burden?

AFib is increasingly viewed as a public health problem due to its increased incidence, prevalence, and adverse impact on the growing aging population. Past studies of the burden of atrial fibrillation have focused solely on the presence or absence of AFib. This binary approach has limited our understanding of the risks for AFib and its actual impact on patient outcomes.

An ideal approach to defining burden would be enhanced by a comprehensive view of how the type (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent), duration, and role of lifestyle and intensive risk factor modification influence AFib burden.

In spring 2025, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Council on Stroke, in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), identified a standardized, internationally applicable definition of AFib burden:6 the proportion of time spent in AFib expressed as a percentage of the recording time, undertaken during a specified monitoring duration.

Why AFib Burden is Important

Utilizing a burden-based description of AFib related to outcomes and treatment strategies may lead to improved risk prediction through earlier classification of AFib type, and application of related treatments; when AFib burden is reduced, outcomes can be improved.7

- The higher the AFib burden, the higher the risk of stroke—particularly in episodes that last more than 24 hours.

- In heart failure, particularly HFpEF (heart failure with preserved ejection fraction), high AFib burden may contribute to cognitive impairment.

- As AFib burden increases, evidence suggests reduced quality of life.

- Reducing AFib burden may assist in preserving cognitive function.8

Benefits of Using a Unified Definition of AFib Burden

Research indicates that AFib burden has a great impact on quality of life than does the duration and number of AFib episodes, suggesting that AFib burden may be the preferred outcome of rhythm control in trials with relatively healthy AFib populations.

A unified, international definition of AFib burden has the benefit of:6

- Allowing for comparability of clinical study data, to expand evidence and establish actionable thresholds of AFib burden in various clinical conditions

- Supporting risk evaluation and clinical treatment decisions in AFib-related disease

- Continuing to promote the development of clinical trials on the clinical relevance of intermittent AFib

- Informing the development of heart rhythm monitoring, particularly validated technology that meets clinical needs.

Clinial Pearls for Cardiovascular Nurses about AFib Burden

Regardless of their role, cardiovascular nurses are actively engaged in the process of AFib detection and treatment. Understanding the AFib burden in clinical practice as well as in research, and the related actions related to prevention and treatment, can help decrease AFib burden and provide higher quality of life for those at risk for, or with, AFib.

- AFib significantly impacts patient health and quality of life.

- AFib burden can be reduced with effective risk factor management.

- Preventive strategies that address traditional atherosclerotic risk factors, with an emphasis on weight loss/maintaining a healthy weight, can reduce AFib burden.

- Ongoing symptom tracking may aid in the detection of AFib—but is only one part of a comprehensive assessment.

- AFib may be asymptomatic, or symptoms may be mistakenly attributed to other medical conditions.10

- Educating patients about tracking symptoms in between appointments is critical.

- The choice between intermittent, long-term, and continuous electrocardiogram monitoring can make a difference in the sensitivity of AFib detection and calculation of AFib burden.

- Extended, continuous monitoring provides the most accurate assessment of AFib burden.

PCNA has a number of tools for healthcare professionals and patients with AFib.

References

- Noubiap JJ, Tang JJ, Teraoka JT, Dewland TA, Marcus GM. Minimum National Prevalence of Diagnosed Atrial Fibrillation Inferred From California Acute Care Facilities. JACC. 2024;84(16). Heart Rhythm O2. 2022;3(5)577-586. DOI: 10.1016/j.hroo.2022.07.010.

- Magnussen C, Niiranen TJ, Ojeda FM, et al. Sex differences and similarities in atrial fibrillation epidemiology, risk factors, and mortality in community cohorts: results from the BiomarCaRE consortium (biomarker for cardiovascular risk assessment in Europe). Circulation. 2017; 136:1588-1597

- Mou L, Norby FL, Chen LY, et al. Lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation by race and socioeconomic status: ARIC study (atherosclerosis risk in communities). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018; 11, e006350

- Guo Y, Tian Y, Wang H, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation in China: new insights into the global burden of atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2015; 147:109-119

- Deshmukh, A., Iglesias, M., Khanna, R., & Beaulieu, T. (2022). Healthcare utilization and costs associated with a diagnosis of incident atrial fibrillation. Heart rhythm O2, 3(5), 577–586.

- Doehner W, Boriani G, Potpara T, et al. Atrial fibrillation burden in clinical practice, research, and technology development: a clinical consensus statement of the European Society of Cardiology Council on Stroke and the European Heart Rhythm Association. EP Europace. 2025;27(3). DOI: 10.1093/europace/euaf019.

- Becher N, Metzner A, Toennis T, Kirchhof P, Schnabel RB. Atrial fibrillation burden: a new outcome predictor and therapeutic target. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(31):2824-2838. Doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae373.

- Tang SC, Liu YB, Lin LY, et al. Association between atrial fibrillation burden and cognitive function in patients with atrial fibrillation. Intl Journal Cardiology. 2023;377:P73-7

- Jansson V, Bergeldt L, Schwieler J, et al. Atrial fibrillation burden, episode duration and frequency in relation to quality of life in patients with implantable cardiac monitor. IJC Heart & Vasculature. 2021;34. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2021.100791.

- Thrysoee L, Stromberg A, Brandes A, Hendriks JM. Management of newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation in an outpatient clinic setting-patient’s perspectives and experiences. J C8. Doi: lin Nurs 2018;27:601–11.

Published on

October 3, 2025

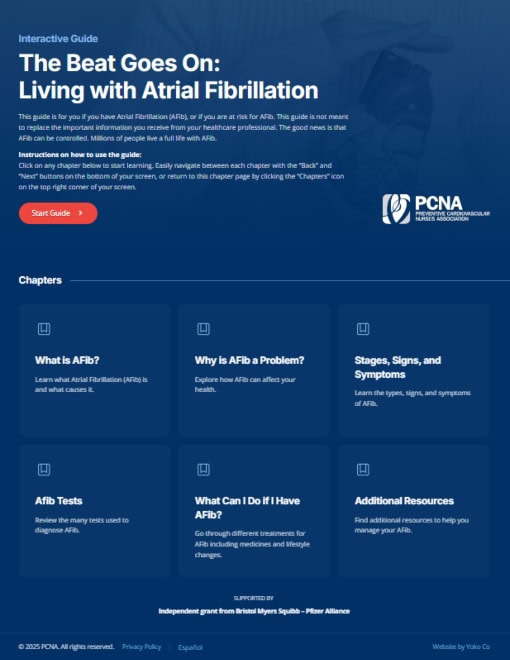

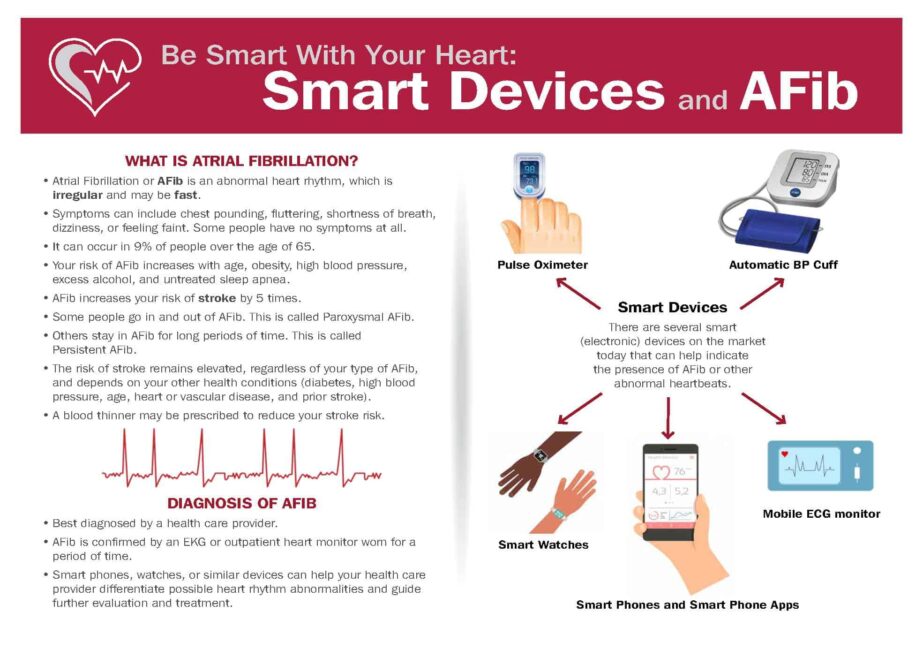

Related Resources

Online Interactive Guides

The Beat Goes On: Living with Atrial Fibrillation Online Interactive Patient Guide

July 30, 2025

Patient Education Handouts

Be Smart With Your Heart: Smart Devices and Atrial Fibrillation

February 09, 2026