What can we be doing to reduce LDL-C to decrease the risk for cardiovascular disease, particularly in our patients with diabetes? Learn from Margo B. Minissian, PhD, RN, ACNP-BC, NEA-BC, FAAN about the role of high blood sugar in cardiovascular disease, effective strategies for lowering LDL-C, and the importance of early treatment.

Episode Resources

- PCNA Lipid Resources for Providers and Patients

- PCNA Diabetes Resources for Providers and Patients

- 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol

- 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease

- IVUS Regression Trials: REVERSAL (2004), ASTEROID (2006); SATURN (2011); GLAGOV (2016); PRECISE-IVUS (2015); JAPAN-ACS (2009)

- COURAGE trial

- VESALIUS-CV trial

- Pleiotropic effects of statins

Thank you to Amgen for their support of this episode.

I’m Erin Ferranti, Board President for PCNA, and I’d like to welcome you to this episode of the Heart to Heart Nurses Podcast. PCNA is the proud home of cardiovascular nurses and one of the leading figures in the fight against cardiovascular disease. We have the resources you need for your day-to-day practice or to follow your passion to new areas of learning and growth.

Geralyn Warfield

I’d like to welcome our audience today to our wonderful conversation with Margo Minissian about LDL-C and diabetes. So, Margo, could you introduce yourself to our audience, please?

Margo Minissian

Absolutely, Geralyn. And thank you so much for having me on today, your podcast. I just absolutely love PCNA and any opportunity to be able to talk about cardiovascular prevention and in this case for diabetes is very close to my heart.

My name is Margot Minissian. I am a cardiology nurse practitioner, and I am the Executive Director of the Geri & Richard Brawerman Nursing Institute as well as the Simms/Mann Endowed Chair at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

I oversee a couple things. I oversee nursing education, professional practice, innovation, research, and quality for nearly 8,000 nurses at Cedars-Sinai. And I really feel like I have about the best job in the entire world getting to do that.

But my heart, and my research, and my work has focused essentially my entire career on preventing cardiovascular disease. So, that’s why I love this topic and it’s personal to me as well, which makes it, I think, extra special.

Geralyn Warfield

Well, Margo, I’m sure our audience can hear not only your enthusiasm for this topic, but also recognizes your expertise. And we’re so grateful to you for being here today. And I’m hoping we could get started talking a little bit about the pathophysiological role of LDL-C in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, or ASCVD.

Margo Minissian

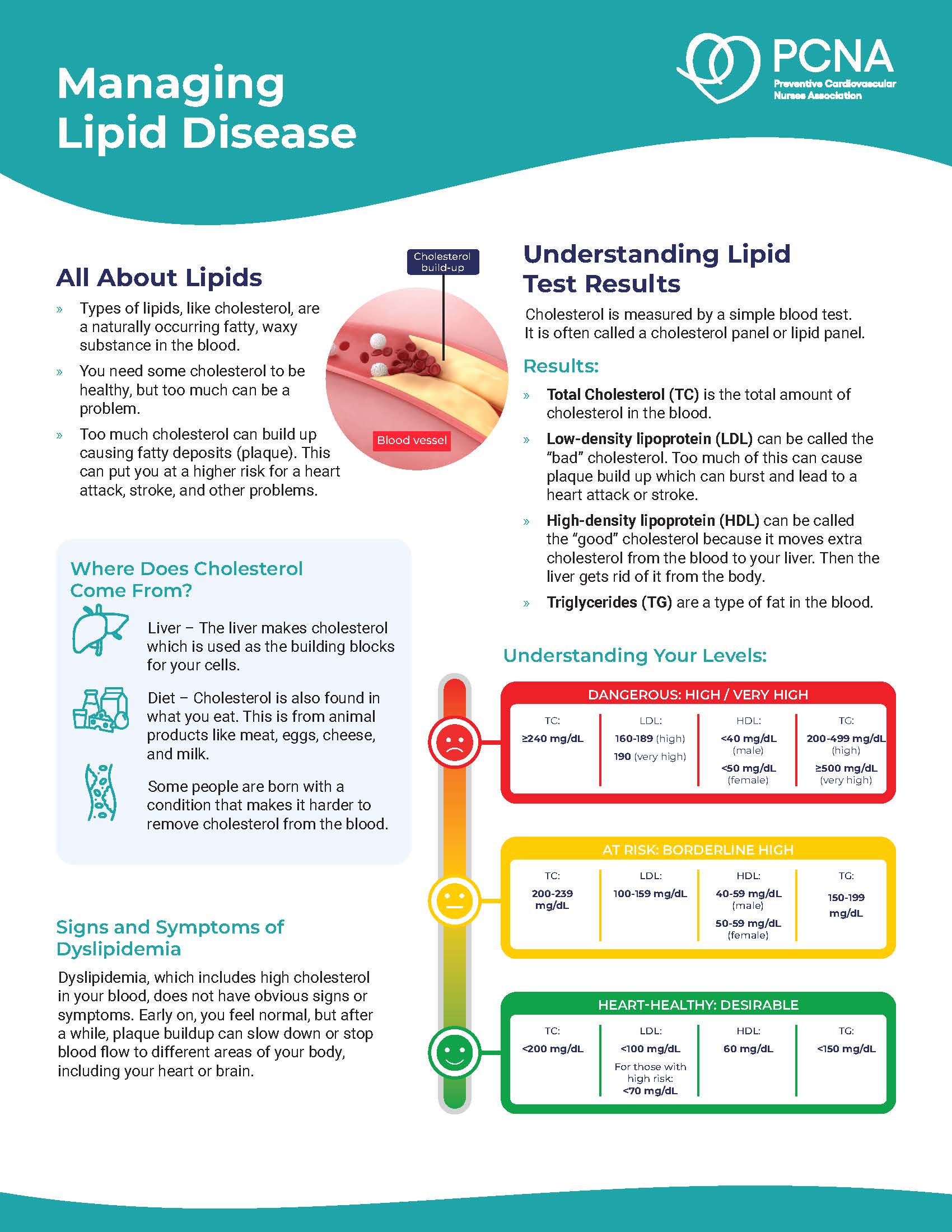

Yes. You know, this is an important and fundamental construct that we actually understand what low density lipoproteins do, and where they should be present—and maybe where they shouldn’t be present.

So, if you look at infancy and when we’re born, and if you look at other mammal species—if you look at a rabbit or a horse or any other vegetarian mammals, they are running their LDLs in the 30s. When we’re born, our LDLs on average are about 32 mg/dL. And so, what happens? Who walks around naturally with an LDL of 32?

There are some cohorts of people that do. There’s a population in Italy, for example, that their LDLs run extremely low, fundamentally. But for the rest of us who have to interact with Western society, in particular, and industrial societies worldwide, our proteins interact and, therefore, trigger our LDL receptors to replicate. And we create more and more of these LDL particles. Simply said, we don’t have enough LDL receptors to clean out the LDL and so then our LDL particles climb up over time. For those of us who have either a genetic mutation, or lifestyle X, Y, and Z reasons, we will see our LDLs climb up.

There are some people that it doesn’t matter how much McDonald’s they eat, they could not get their LDL as high as it’s showing on their lab report. And so those are those genetic mutations. And there are three of them that are commonly known. So, some people just have an LDL receptor mutation. Some people have a PCSK9 inhibition issue. And some other people will have an Lp(a) gene mutation. And so those are the three common ones; there are several.

And so, there are different reasons why people will have very high cholesterol. Our discussion today won’t really include the homozygous familial hyperlipidemics. These are people that, you know, really have a hard time living past the age of 30. Typically, most of us in the clinic space are seeing heterozygous familial hyperlipidemia, and that’s typically what we’re treating or some variant of it.

Geralyn Warfield

So, when you’re speaking with the nurses that you work with and they are dealing with patients who maybe don’t have a great understanding of how these LDL, Lp(a), PCSK9 levels or receptors affect their risk factors for cardiovascular disease, how can we better describe that for patients so they can understand it?

And I have to tell you, Margo, I have not in recent years heard it explained quite so capably as you’ve just done for our audience. So, thank you for that.

Is that the kind of conversation, for example, that you would encourage your nurses to have with their patients?

Margo Minissian

I do. And all of my patients have heard that soapbox that I just gave you. It was something that I had learned prior to the PCSK9 inhibition drugs coming onto the market.

And so, the big question that we were really pondering on was, is there a ‘too low’ for LDL? And we just couldn’t answer it.

Up until like 10 years ago, we had some IVUS [intravascular ultrasound] trials. They had looked at, they had like, on average, I think they were like the age of like 20 to 40, they were military soldiers who had died in combat, and they had done autopsy on them. And they could see that some of these individuals had fatty streaks or had plaque. And you know, that was like when the beginning of just kind of looking at some of this like, wow, how is it that you have plaque but like their LDLs were quite low? And why would you lay down plaque?

And then, we’ve looked at risk estimation, that’s like the…we’ve been chasing risk calculations for decades and trying to predict, trying to predict.

Well, look at breast cancer. Look at colon cancer. We’ve gotten to a point where for cardiovascular prevention, everyone else is just looking for disease. Would anyone be comfortable saying, “Oh, I did the breast cancer risk score. And mine says that I’m low-intermediate. So, I think I’m okay.” No, you go get a mammogram and you look for disease.

And so that’s really where we’re going is we now have drugs that are capable of getting LDL very low, back to, going back to infancy stages. And we now also have imaging technologies that enable us to cut past the risk score and to quantify and treat disease.

And that’s really where the pivot is happening in science today for cardiovascular medicine, and it’s very exciting.

Geralyn Warfield

Well Margo, I really respect the fact that I think some patients are well aware of their LDL-C levels and may or may not understand what the ranges are, as you described, that lower is better. Whatever that is, lower can be better.

And I think clinicians overall are making that pivot as you’ve just described also, that it can be lower than it is and still be safe because there has been a lot of conversation about how low is too low.

So, for individuals who are working with patients that have, for example, high levels of LDL-C, do you have any clinical pearls in helping them understand what that risk means? I have, for example, seen visuals that include the pictures of individuals and X number of people are a slightly different color or a shade of a color to try and describe that. But what can we do to help people understand that you can make changes today that will affect your risk for the rest of your life?

What kind of clinical pearls could you offer?

Margo Minissian

Absolutely. You know, what we know is the sooner that we treat someone with high cholesterol, that they have a cumulative benefit over time. Meaning if I can convince someone who’s meeting national guideline criteria for treatment as early as possible, this is all about timing, getting someone on the medication as fast as you possibly can, the right patient. That they have a cumulative benefit over time, where we literally watch their hazard curve go in the direction of health as opposed to literally death. And I think that that’s really key.

And then it’s also very important, we also don’t want people taking pills or injectables or anything else for just the sake of doing it. There’s expense, there’s minimal risk, but there is always risk when we put something into our bodies.

And then you want to do this risk-benefit analysis. And I argue, think of the risk of not taking it versus the risk of, “Gosh, I might, you know, I might have a myalgia. I might have, you know, a rash.” And those are things that, you know, we can mitigate. But I think getting down to the risk stratification as quickly as possible, identifying those patients at highest risk.

Today, we are talking about this in the setting of the diabetic patient, which is a cardiovascular risk equivalent. And so, these individuals, in my opinion and several others, should be having an LDL that is 55 or less. And we now have the capability of treating patients easily to those metrics.

Here’s one other thing I will tell patients. When we think about LDLs that are very low, there’s really no good reason to have low density lipoproteins floating around in our periphery, truly. They really don’t have a positive role there.

And our adrenals actually help provide cholesterol to our brain, for example. So it’s not like we need to have this extra floating-around cholesterol so that we can have mental clarity, or that, you know, they’ve looked at it in regards to dementia and Alzheimer’s and all we know is that the lower your LDL—the lousy one, the bad one, the inflammatic one—that we have less strokes, less heart attacks, less bad things happening to people. And I really think that that’s the take home message.

Geralyn Warfield

We have been talking about LDL and other factors for ASCVD, and we are going to take a quick break.

Geralyn Warfield

I’d like to welcome back our audience to our discussion of LDL-C, particularly when it comes to diabetes and other factors for risk.

And Margo, I’m hoping you could expound just a little bit more on the pieces that you had described a little bit in our time before the break, which was really that diabetes is connected, really significantly, to the development of cardiovascular disease. And could you maybe describe a little bit more about what that looks like?

Margo Minissian

Yeah, absolutely. You know, Geralyn, I’d like to share too, you know, I had said that this is very close to my heart. And the reason why it is, is because my father was a diabetic and he died of heart disease at 46. And so, understanding his phenotype and why he landed where he landed was important to me.

And I think that people can feel falsely reassured that if they are managing their lifestyle, and they’re managing risk factors, that they can kind of evade needing to treat their high risk for cardiovascular disease development.

But the fact of the matter is that they are at a two- to four-fold increased risk of developing heart disease prematurely compared to someone who is not a diabetic. And so, we therefore treat them as a cardiovascular risk equivalent, and that everyone who has diabetes really should be on the highest-tolerated statin dose.

Geralyn Warfield

So, Margo, what could you tell us about the effects of statins, particularly in those patients with diabetes? Is it any different than any of our other cardiovascular patients?

Margo Minissian

Well, it’s interesting because we know that diabetes has a lot more inflammation associated with it. And if you look at all the bad diseases and things that people can get, what’s the common thread through all of it is inflammation.

So, statins are known to have very positive pleiotropic effects that help improve inflammation and the endothelium. And so therefore, they are cardioprotective, and everyone should be on one. You know, I am yet to look at the exception. And, you know, we’re really putting them on their highest tolerated dose.

And I do have creative ways of getting all patients on some form of a statin to help them be able to achieve that.

Geralyn Warfield

Margo, could you please explain for us how insulin resistance and hyperglycemia actually help increase atherogenesis in those LDL particles?

Margo Minissian

Yeah, absolutely. Let’s face it, sugar is sticky. And if you have high glucose levels, over time, these LDL particles, they are sticking together and creating these soft, lipid-rich-core atherosclerotic—it’s like a dam in your blood vessel, if you will, to keep it quite simple.

And so, the statin is sort of like the ‘Liquid Plumr®’ of medications. It’s like good old Drano® for cholesterol. And, you know, that’s a really simplistic way of thinking about it. But that is really essentially what it does is it sucks the inflammation out of that lipid-rich core and helps to stabilize the plaque that is present and helps to prevent plaque from lying down.

Now we know, too, that these high-risk metabolic patients that we see—and you know who they are, they are the apples and the oranges and they’re not the pears. And, you know, so they have this visceral fat that accumulates at their waist. They oftentimes too will have thinner arms and legs. So, they’re lacking lean muscle mass, and they are having more fat around their waistline. That when these patients are placed on a statin, some of them will convert into becoming diabetics.

Now, when we looked at the COURAGE trial, we saw that these patients still were cardio-protective, even though they converted into having diabetes. It’s likely because they were converting into becoming diabetics regardless. But there is a small rate of patients that when they’re put on statins, you might see a bump in the hemoglobin A1C.

When I see that happen, statins are a heterogeneous population of drugs. So, they are sisters that don’t look alike. What does that mean? Many of them have different CYP pathways for cholesterol metabolism. So, if I see someone who has a bump in their hemoglobin A1C, or they’re describing a myalgia or a muscle ache, or a stomach upset on occasion, like maybe like some alopecia, I will switch them to a statin that—and depending on if they need high intensity statin or not—the two high-intensity statins luckily utilize a different CYP pathway.

So, this is a lot of biochem just to simply describe to you, you can switch the drug and oftentimes mitigate the side effect that you were seeing.

And so, we know that some people are just poor CYP3A4 pathway metabolizers, or they’re a cardiac patient and they’re on Plavix® and amlodipine and other medications that are all using the 3A4 pathway. And so, some of this is just avoiding drug-drug interactions, or some of it is trying to figure out which CYP pathway is a good, that they happen to be a good metabolizer.

And then, if you find like you’re scratching your head and they’re having tons of side effects, and you’ve tried three or four statins, that’s actually when I reach out to pitavastatin, because it actually doesn’t use a CYP pathway to metabolize. And it’s about as effective as atorvastatin, and it’s in 1-4 milligrams. So, you can use very little of it and get a really good effect. You get all the positive pleiotropic effects and you get very little of the side effects. So, you know, I always like to mention it because it’s now off-patent and, you know, we just have a great arsenal of medications.

And we also know that when we’re in need of adding on additional therapies for that LDL-lowering that they have a synergistic effect—statins do with, say, a PCSK9 inhibitor. The PCSK9 inhibitor works better with even just the littlest dose of statin on board. Even with alternate day dosing, it does better.

Geralyn Warfield

So, Margo, I have one final question for you. We have covered a lot of ground today in our conversation, but what do you think is your one key takeaway for our audience from our conversation.

Margo Minissian

If you’re a clinician and we know that you’re strapped for time, and we know that you’re strapped for resources, you really want to be able to dive in, and dive in quick, and figure out if that patient has plaque or not.

So coronary calcium scoring—and if anyone is even remotely having any symptom above their waist, please think about using advanced imaging, such as a CT scan with Heartflow or something of that nature that can plaque quantify. Plaque quantification is such a cool technology that is emerging and it is available at most major medical centers. And then that way you can just dive in and get that patient on the right therapy right away instead of things that would take us six months to a year to discern.

That could be a year that somebody was already on treatment with an LDL down to 44, for example. And that’s really where the money is. If we and our patients want to be happy and healthy and dancing into our 90s, that’s the way to get there.

Geralyn Warfield

Margo, thank you so very much for sharing your expertise and your enthusiasm with our audience today. We look forward to all being able to dance into our 90s thanks to your great suggestions for ourselves and for the patients with whom we work.

I’d like to thank Amgen for their support of this particular podcast series.

And I know that Margo mentioned a few resources, a few trials and other things. We will make sure to put all that information in the show notes so you can always look for information there. And also, listen to the other related podcasts in this series.

This is your host, Geralyn Warfield, and we will see you next time.

Thank you for listening to Heart to Heart Nurses. We invite you to visit pcna.net for clinical resources, continuing education, and much more.

Topics

- Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD)

- Diabetes

- Lipid Management

- Risk Assessment and Management

Published on

February 3, 2026

Listen on:

PhDc, ACNP-BC, CLS-BC, CNS, AACC, FAHA

Related Resources

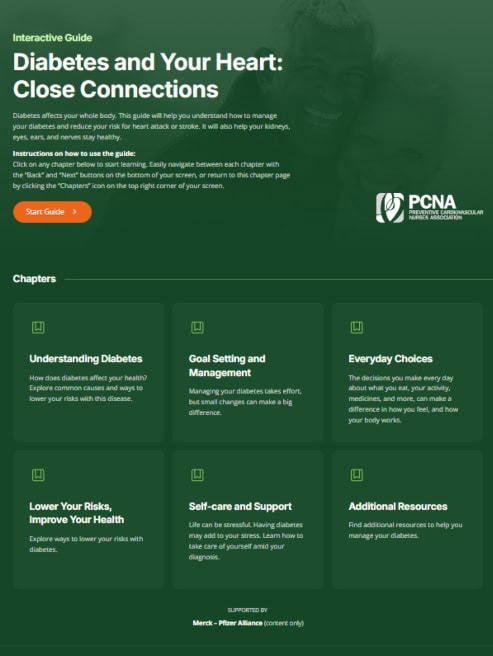

Online Interactive Guides

Diabetes and Your Heart: Close Connections Online Interactive Patient Tool

June 12, 2025