Learn about the diagnosis and treatment of resistant hypertension (also called apparent treatment resistant hypertension) from guest Vivek Bhalla, MD. What is the prevalence of this disease? What does the screening process look like, and what does the research support in terms of guideline-directed medical therapy?

Episode Resources

[00:00:00] Welcome to Heart to Heart Nurses, brought to you by the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. PCNA’s mission is to promote nurses as leaders in cardiovascular disease prevention and management.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We are very excited today to have the opportunity to speak with Vivek Bhalla, who’s going to speak with us about resistant hypertension. We are so grateful to you for being with us today. Why don’t you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Vivek Bhalla (guest): Thank you for having me on the show, Geralyn. My name is Vivek Bhalla. I am an Associate Professor of Medicine and Nephrology at the Stanford University School of Medicine. I have done research in hypertension and in different forms of resistant hypertension.

I also see patients with this condition, and I direct and I founded the Stanford Hypertension Center. And our, [00:01:00] specialty is in seeing patients with resistant hypertension, with secondary forms of hypertension, uncontrolled hypertension, and early onset hypertension.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Well, it sounds like we’ve got a great expert at the table with us today, and I’m wondering if you could just start with the very basics for us and tell us a little bit about resistant hypertension, just overall.

Vivek Bhalla (guest): Sure. So resistant hypertension has a longer name; probably we should use the term “apparent treatment resistant hypertension,” which would refer to patients that have hypertension, in which you’re fairly confident that they’re taking all of their medications, and yet their blood pressure is still resistant to that treatment.

So more formally, the redefinition is that if a patient is taking three or more medications for high blood pressure, one of which is a diuretic of some kind or a water pill, and yet their blood pressure is still above the treatment goal, that treatment goal being greater than 130 over 80 millimeters of mercury, [00:02:00] then that person would be classified as having resistant hypertension.

There’s a second definition, which is that if you’re taking four medications, four classes of anti-hypertensive medications—it doesn’t so much matter which class of medication—or if you’re able to get your blood pressure under control, once you meet the barometer for medications, you fall under the, under the, under the umbrella of resistant hypertension.

Geralyn Warfield (host): So, once you’ve identified these individuals that have resistant hypertension, or the longer name, which you’ve described and I have not written down, can you tell us what we would do with someone with resistant hypertension?

Vivek Bhalla (guest): Sure. I think it’s also important at the outset to describe why we would care, right? Why would we care about resistant hypertension? Why? Is this just an inconvenience where you have to go to the doctor more and take more pills than if you can get away with one or two medications?

Why would we care about having resistant hypertension?

We care [00:03:00] because if you examine individuals that have resistant hypertension, they have higher rates of the things we care about. They have higher rates of stroke. They have higher rates of a heart attack or a myocardial infarction. Higher rates of heart failure. Higher rates of kidney disease. And so, if your blood pressure is uncontrolled, or is resistant to treatment, you’re in a higher cardiovascular risk category. So that’s why we care.

In terms of what to do when you encounter someone with resistant hypertension, I think it’s really important to, to get back to basics, if you will. You want to think about the factors that exacerbate blood pressure, whether you have essential non-treatment resistant hypertension, whether you have resistant hypertension, or whether you’ve identified that a patient has a secondary or oddball or rare cause of hypertension—exacerbating factors are kind of common to all of those.

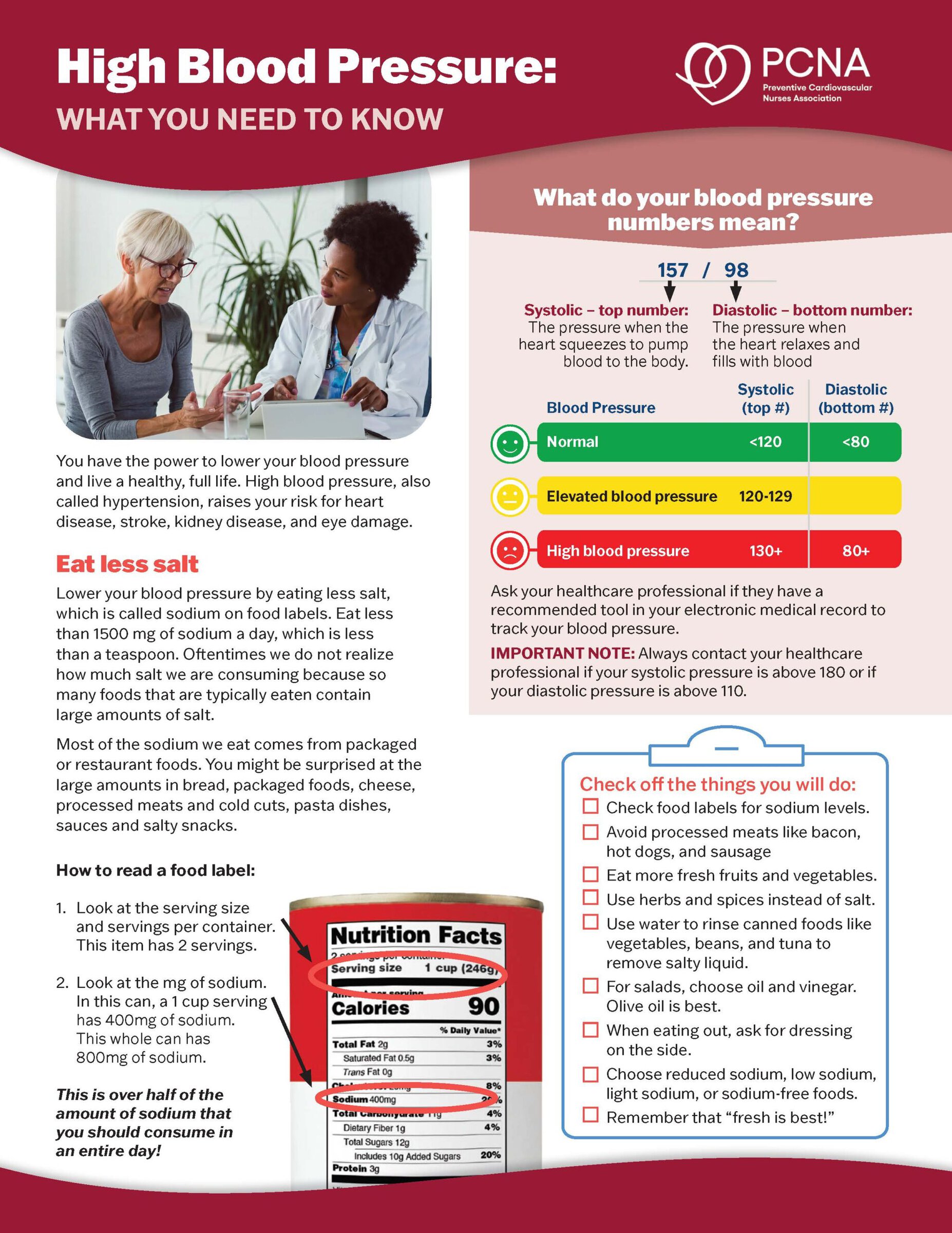

So, what would those be? Well, the high sodium diet [00:04:00] is probably the most common one that we encounter in the population today. A low sodium diet would be anything less than two grams of sodium–or 2300 milligrams more formally—in 24 hours. So that would be counting the number of milligrams of sodium on a package insert and having it fall under that number.

That’s really difficult to do. It’s really difficult to do the math every day, to estimate it just right, to get portion size right so that you can do the calculation. The other way we can measure that is more formally with a 24-hour urine collection, which is both cumbersome and something that’s not very widespread.

Probably the other way to estimate whether someone has a high salt diet is to really ask about processed foods. I typically will say that if a patient is taking processed foods at least once, at least once a day, or several [00:05:00] times a week, that they’re likely to encounter a higher sodium content in the foods because it’s processed.

So, they’re likely to have a higher sodium diet. That is not terribly rigorous, but doing it more rigorously is more difficult with dietary questionnaires, a referral to a dietician, and/or a 24-hour urine collection. So, I generally will ask patients, “Do you eat meat? Do you eat marinades on meat? Do you eat processed food? Do you go out for dinner?” That question was very different during the pandemic, but now, as the pandemic is hopefully slowing down, and before the pandemic would ask about eating out, because that was usually a good proxy for a high sodium diet. So that’s one exacerbating factor.

Another exacerbating factor that is probably common to many cardiovascular risks, resistant hypertension is no exception, is obesity. So, an elevated body mass index, sedentary lifestyle would be another.

Probably the [00:06:00] factor that is particularly relevant to resistant hypertension is obstructive sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea is quite underappreciated in the general population, but it’s something that we screen for in all patients with resistant hypertension, because when you study this, it turns out that at least three in four patients with resistant hypertension have some form of obstructive sleep apnea.

And if you identify it, and you treat that with some sort of device, you can actually reduce the blood pressure substantially. When I say substantially, I mean 10, 15 millimeters of mercury. That’s a big drop in blood pressure. And so, one wouldn’t want to let something like obstructive sleep apnea go unchecked. And sometimes resistant hypertension is our lucky clue. So that’s one of the reasons we screen for it.

The other thing that we think about in patients with resistant hypertension, is looking for secondary causes of high blood pressure. Because if you have resistant hypertension, it’s much more likely that you [00:07:00] have a second cause of hypertension rather than having essential or idiopathic hypertension.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We are talking today about resistant hypertension and we’ll be right back.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Today we have the great opportunity to talk with Vivek Bhalla about resistant hypertension. And my next question for you is about screening, and it’s particularly about screening for PA and how that fits into this picture. Could you discuss that a little bit for us please?

Vivek Bhalla (guest): Sure. So, in patients with resistant hypertension, this apparent treatment resistant hypertension, and you’re kind of checking your boxes about all the exacerbating factors that they have. It’s really important to consider as part of one’s diagnostic evaluation to consider secondary causes of hypertension.

Of those secondary causes, the most common one is PA, or primary aldosteronism, and that’s super important to screen for. One, because it’s the most common and this is the population in which you’re likely to find it. [00:08:00] And, two, you know, kind of gets at the ‘why do we care?’ question. Why would one want to know if somebody has primary aldosteronism or PA?

Well, even as a subset of resistant hypertension, or just in general, if you compare patients with PA to patients with essential hypertension, the patients with PA have a higher rate of the things we care about: stroke, heart attack or myocardial infarction, heart failure, kidney disease.

So letting aldosterone, which is the circulating hormone NPA, letting that go unchecked and untreated, can lead to these higher risks, even when you account for the blood pressure. So, let’s say you have two patients and one has essential hypertension, and they’re on two or three medications for blood pressure, and their blood pressure is 140/90.

You can treat that and address secondary causes, maybe add medications. But [00:09:00] if that same patient is on two or three medications and has primary aldosteronism as a exacerbating factor or as a, as a sole cause of that high blood pressure, that person’s at a higher cardiovascular risk. And this has been found in any number of studies.

And so that’s why we care. That’s the reason we would want a screen. And to screen for this condition, it’s actually not hard. It’s really easy. It’s a blood test. It’s a morning blood test. You get a plasma aldosterone level and a plasma-renin activity. It’s available at most labs. Oftentimes they will send it to a few select commercial labs, but the results come back in about four to five days.

And so, it’s a very tractable thing to screen for. It’s certainly easier to screen for this than it is to screen for other common diseases that we screen for all the time.

So, as a society, we screen for things like breast cancer. We screen for colon cancer. [00:10:00] If you take breast cancer as an example, and you look at, you look at the death rate of breast cancer worldwide deaths are somewhere between 680,000, 690,000 a year.

And you look at the screening rate for breast cancer, as a society, we’re doing a pretty good job. In the United States, our screening rates for breast cancer with a mammogram are about 75, 76% according to the Centers for Disease Control. That’s a pretty good number. That means it’s not as high as we would want it to be, but we are doing a pretty good job with implementation of that screening guideline.

If you look at resistant hypertension and say that that population needs to be screened for PA according to multiple international societies, the death rate, worldwide, for resistant hypertension is, it’s conservatively, certainly no lower than breast cancer. It’s probably much higher than that, around the world in any United States.

But our screening rates are [00:11:00] horrifically low. They are two to 3%. That’s if you look at resistant hypertensive patients in the United States, if you look at a single center, if you look at Canada. 2% is horrifically low. Compare that to 75% for breast cancer. We need to be screening for this condition far more than we are as a society, and we’re not doing a good enough job now. That’s the reason we need to screen for PA.

Geralyn Warfield (host): So, I hear that your call to action for us is to be very attentive to what the symptomology might be, to be cognizant of what we should be looking for, and that the screening is very, very important.

So, let’s imagine that our listeners now have someone that they have in practice that they’ve identified as having had, or having, I’m sorry, resistant hypertension. What are the next steps?

Vivek Bhalla (guest): So, the next steps are to consider the secondary causes among which the most common one to screen for is primary aldosteronism. [00:12:00]

Probably one of, the myths that we should debunk right here and now is that, when you look at who gets screened, if you have high blood pressure in a patient in clinic, and they have a low potassium, and they have an adrenal nodule on a CAT scan that they got for a traffic accident a few months ago—and I’m just making up this case as we go—but if you have that scenario clinically, that person is more likely to get screened.

Because when we’re in training, we learn about what primary aldosteronism is, what Conn’s syndrome is, and this, this rings a bell. This sounds like a classic case of PA.

But you don’t need to have an adrenal nodule to have PA. You don’t need to have a low potassium to have a PA. In fact, two thirds of patients, the majority of patients with PA, they don’t have a low potassium. So, all you need is that resistant hypertension.

And that’s why the American Heart Association, the [00:13:00] Endocrine Society, many other societies recommend resistant hypertension=screen for PA. Get a blood test.

One of the other, I think, impediments to getting screening is that, is there some preparation that needs to be done? Do you need to take patients off their medications? That’s a really good question, right, because what would that mean for a provider? You would have to stop medications in a patient with resistant hypertension.

Well, we all know what’s going to happen when you do that? The blood pressure is going to go up, potentially. It’s going to cause anxiety for the patient. It could be potentially dangerous. You might have to do more visits or be more attentive to that particular patient. You could see how implementing screening guidelines might be difficult in that scenario.

And that is why most guidelines that recommend screening, they don’t recommend that you stop medicine. They recommend that you screen for this condition [00:14:00] with a simple blood test on the medications that they are right now.

How to interpret that test is going to be a little bit different if you’re on certain medications, certainly, but probably the only medications that a patient needs to be off of are mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, or other potassium sparing diuretics, such as amiloride, or triamterene.

We know from studies that the medications I just mentioned are not prescribed for the majority of patients with resistant hypertension. And so, in most patients with resistant hypertension, odds are you can implement screening pretty quickly with getting a blood test.

Geralyn Warfield (host): So, in general, how would we go about treating a patient with resistant hypertension?

Vivek Bhalla (guest): So, that’s also a good question. So, sometimes when we screen for something like PA, we think about, well, why don’t we just treat them, [00:15:00] right? Why don’t we just treat them with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist? Maybe my patient doesn’t want to go through all the, jump through all these hoops to get a diagnosis of PA and, and, go down that diagnostic tree. Why don’t we just use a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist?

And that brings up another issue, which is, what is the way that you’re supposed to treat someone with resistant hypertension who either screens negative for PA, or doesn’t get screened at all? And there have been some small observational studies that have suggested mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists would be a good next drug for most patients with resistant hypertension.

But, fortunately, there has been a rigorous randomized controlled trial in the last few years, that actually proved that, also. So, that was called a PATHWAY-2 trial that came out of Europe. It was a randomized double-blind, [00:16:00] placebo-controlled, crossover trial where patients got either a placebo drug, or spironolactone, or bisoprolol, or doxaxosin.

So here we were putting patients with a clinical diagnosis of resistant hypertension, and really rigorously testing, ‘What’s the next best drug? Is it a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist? Is it a beta blocker? Is it an alpha-1 antagonist?’

Spironolactone was significantly better than placebo, and significantly better than either bisoprolol or doxaxosin in this trial.

So, this trial was about 230 patients, was the largest trial of resistant hypertension, and was done very recently, and really proved that the next best drug for resistant hypertension was a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist. So, whether we, you know, whether we go down the route of screening or not, this is the next best drug. [00:17:00]

That then circles back to the question, why bother screening at all? Because if you have someone with resistant hypertension, and I just got through saying, “Well, there’s this really important disease called primary aldosteronism, and you need to, you need to screen for it, right? We’re not screening at all. It’s a public health hazard. We need to be screening more patients.”

And at the same time I turn around and say, “Well, no. The treatment that you would use regardless of whether you screened, is the definitive targeted therapy that is used for primary aldosteronism.”

It begs the obvious question, why would one screen?

And so you could say, well, is there any data that screening plus a…and then going down the route of potential surgery, which is, you know, the end result of screening, which would be a unilateral adrenalectomy. Is that any better than just going straight to empiric therapy?

And the answer is probably, the, the answer is [00:18:00] there’s no randomized control trial. That would be really hard to do. You’d be taking a drug that’s cheap and not really being touted by any particular drug manufacturer. You’d be doing a sham surgery plus drug in one arm, and you’d be doing a real unilateral adrenalectomy plus placebo in the other arm, and then looking to see who does better over time with less cardiovascular outcomes.

I don’t believe that that trial’s ever gone actually, practically, happen. So, we’re not going to get a randomized control trial to answer this question.

But there have been other studies that have been done, including a trial that I don’t think, or a study that I don’t think, gets enough press. There was a paper in 2015 by Lubits, et al, that was a cost effectiveness analysis of patients with resistant hypertension. And asked this question, “Should you screen and do a CAT scan? Should you screen and do an adrenal vein sampling? Should you screen and do all that stuff and then do surgery? Or should you just treat?”

[00:19:00] And the answer was, you should screen and do all that stuff because the proportion of patients that you find, and do more testing, and do surgery: when you take into account, cost of and, patient-related health metrics, and quality of life, the screening versus treatment alone won out in terms of a rather acceptable quality per adjusted life year rate going forward than just treating empirically.

Also, international guidelines, for that and other reasons, endorse for screening and going down the right of a diagnostic tree other than just empirically treating. So that’s why, probably, the best evidence of why we would recommend screening, and considering PA, and attendant tests after that.

And we have to [00:20:00] also remember that primary care providers don’t need to be responsible for all of those things. I think the most important thing is getting patients through that first step and getting the screening done.

And if, if that test is negative, and you want to, you want to treat patients empirically, mineralocorticoid, receptor antagonists are the next best step anyway.

When it turns out, when we looked at who was getting screened, people who were taking mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists eventually were, were much more likely to have been screened.

So, I don’t think providers in this day and age, are empirically treating in lieu of screening. I just think we’re not thinking of the diagnosis. So, I think we need to be aware of this diagnosis. We need to accept it for what it is, which is, it’s super common and super dangerous with higher cardiovascular risk And we need to think about it whenever we have a patient with resistant hypertension.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Do you have [00:21:00] any resources that you would recommend to audience members who want to learn more?

Vivek Bhalla (guest): Sure. So probably one of the best resources is the scientific statement on resistant hypertension by the American Heart Association. Robert Carey is the primary author on that, I believe that was published in 2018.

There’s also a primary aldosteronism foundation that was started recently. It’s a patient-centered organization for this condition. I would also endorse that.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Is there anything else that you would like to add that we’ve neglected to ask you?

Vivek Bhalla (guest): Not at all. I just wanted to thank you for the opportunity to address this condition, which is near and dear to my heart. And just remember that you can always reach out to us at Stanford and the Stanford Hypertension Center if you have further questions.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Wonderful. Thanks for providing not only great information, but great resources for us to be able to learn more, even after this podcast is done.

We have been on with Dr. Vivek Bhalla, talking about [00:22:00] resistant hypertension. This is your host, Geralyn Warfield, and we will see you next time.

Thank you for listening to Heart to Heart Nurses. We invite you to visit pcna.net for clinical resources, continuing education, and much more.

Topics

- Hypertension

Published on

April 4, 2023

Listen on:

MD

Related Resources