Over 1 billion people worldwide are affected by the chronic condition of obesity, which has implications for their heart, kidneys, and other body systems. Guests Anita Rich, DNP, RN, CHFN, CDCES, FAAN, and Jane DeMeis, describe impacts on the body, treatment options, and one patient’s journey.

Episode Resources

- PCNA CKM tools and resources

- 2025 ACC Expert Consensus Statement on Medical Weight Mgmt for Optimization of CV Health

- Adiponectin, Leptin, and CV Disorders

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Adult Obesity in the US

- Cardiometabolic Syndrome: A Global Health Issue

- Taking Aim At Belly Fat

- Gender Disparities in People Living with Obesity

- Systematic review and meta-analysis suggests obesity predicts onset of CKD

- AHA Weight-Loss Strategies for Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension

- Renal Fat Accumulation Assessed by MRI or CT and Metabolic Disorders

Thank you to Novo Nordisk for their support of this episode.

[00:00:00] I’m Erin Ferranti, board president for PCNA, and I’d like to welcome you to this episode of the Heart to Heart Nurses Podcast. PCNA is the proud home of cardiovascular nurses and one of the leading figures in the fight against cardiovascular disease. We have the resources you need for your day-to-day practice or to follow your passion to new areas of learning and growth.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (00:19)

I’d like to welcome our audience to today’s episode where we are going to talk about Cardio-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome or CKM syndrome. I have two wonderful guests with me today and I’m going to let them introduce themselves to you. Anita, could you start off, please?

Anita Rich (guest): (00:34)

Sure, I am Anita Rich. I am a nurse of 44 years. I’m also a senior clinical instructor at the Emory University School of Nursing.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (00:44)

And Jane, how about you?

Jane DeMeis (guest): (00:46)

Yes. Hi, I am a patient. I have CKD. I’ve had it for almost 20 years now. Currently I am on dialysis. Actually, I thought I was going to have to tell you all I couldn’t do this podcast because I got the call Monday night [for a kidney transplant].

Geralyn Warfield (host):

Oh, my gosh.

Jane DeMeis (guest):

I was so excited. We went to the hospital and everything and the kidney was not good.

Anita Rich (guest):

I’m sorry.

Jane DeMeis (guest):

Very disappointing, but we muster on because we don’t have a choice.

Anita Rich (guest): (01:15)

I’m sorry. Yes.

Jane DeMeis (guest): (01:17)

So yeah.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (01:18)

Well, thank you so very much to both of you for being with us today. And I know our audience has a great deal to learn from you all, and from both of your perspectives, from the healthcare provider perspective or healthcare professional perspective, and the patient perspective. So, thank you very much for being willing to be here today.

This, just for our audience to know, is the 3rd of a 3-part mini-series on this particular topic. So, if you have some questions about this, you can refer to the show notes and we’ll talk about that again in a little while, or you can actually listen or watch some of those other episodes. So, we’ll talk about that a little bit more later.

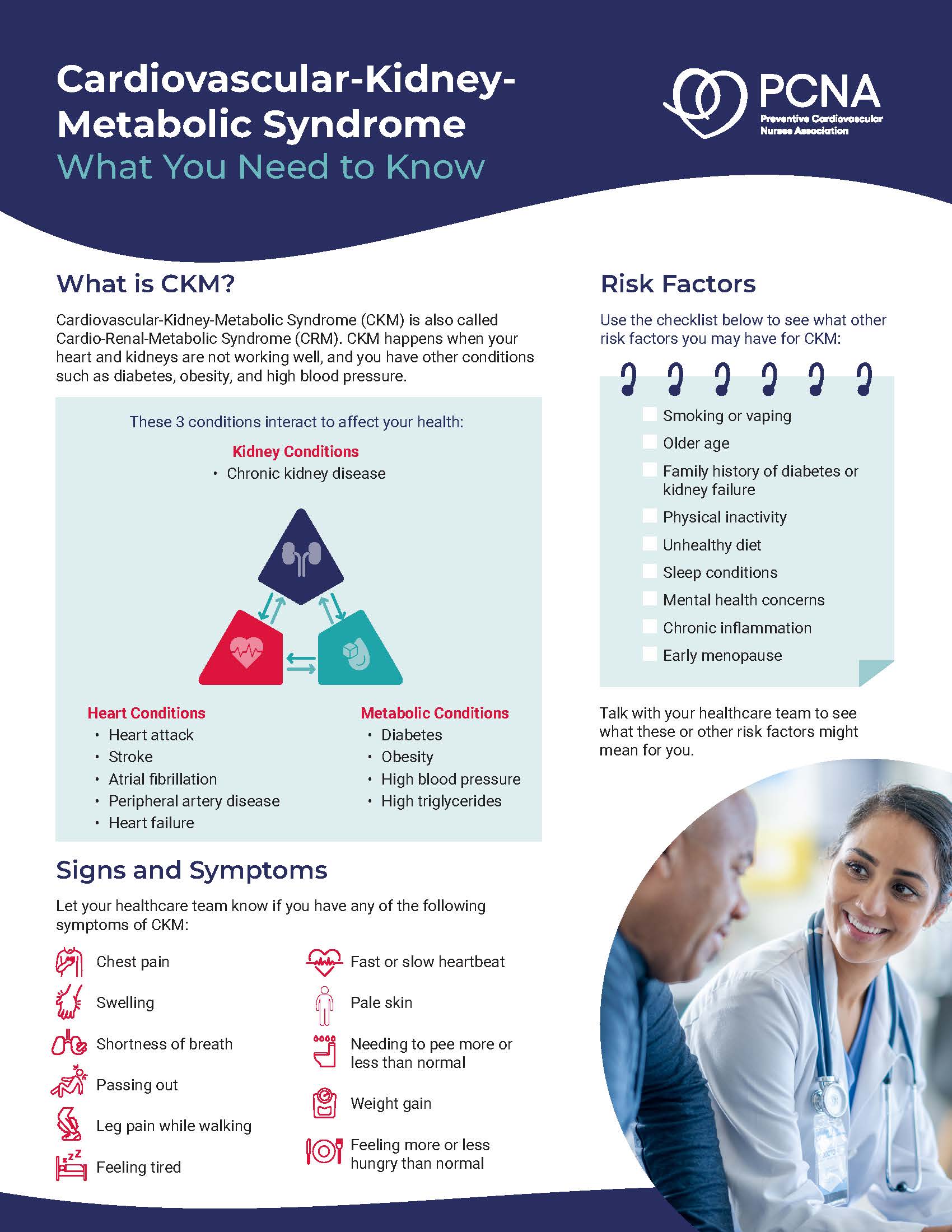

But first of all, our previous episodes have talked a little bit about CKM syndrome or CRM syndrome. And we’ve talked about all the contributing factors when it comes to heart and kidney. But Anita, this particular topic today that we’re going to focus on has to do with the obesity arm of this many-faceted syndrome. And could you talk a little bit about how obesity contributes to the development of these diseases?

Anita Rich (guest): (02:19)

Yes. And again, thank you for inviting us.

I would like to connect the dots a bit, if I may, regarding obesity and how it relates to cardiac and renal or kidney disease.

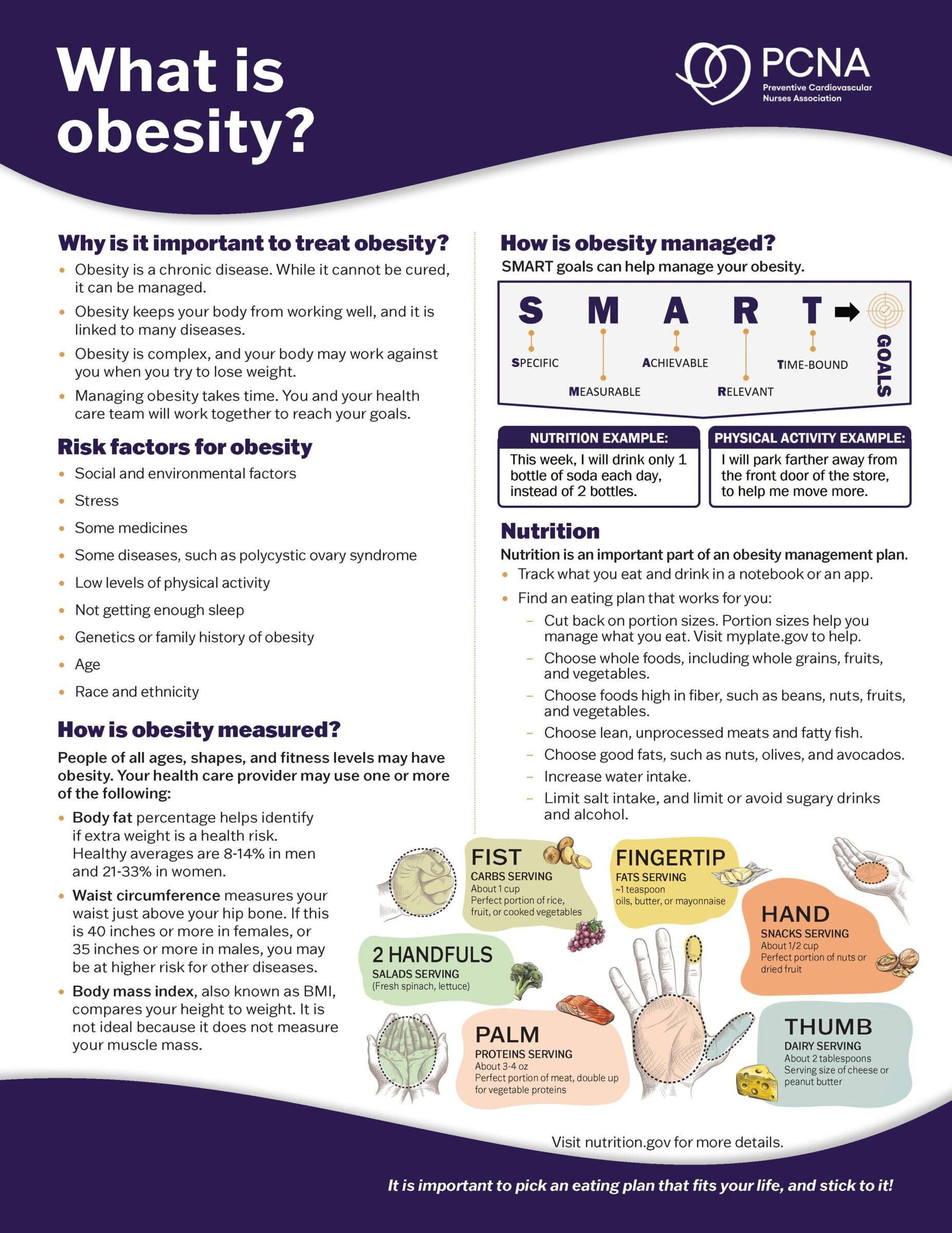

So, I’d like to start with defining and talking a little bit about obesity itself. And we define that as someone that has a body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2. Severe obesity is defined by a BMI ≥ 40.

But we also need to keep in mind that a BMI is really a good estimate for most people, but it can also underestimate body fat for older adults or people that have low muscle mass. And it can overestimate body fat for the people that are especially muscular.

And obesity is a chronic illness. It’s considered a global pandemic, another opportunity to use the word pandemic, in its proportions.

It affects over a billion, that’s with a B, adults worldwide and over 100 million adults in the United States. So, more than 40% of the adults in the United States have obesity, and over 22 million adults or about 9.4% have severe obesity. But in the last 30 years, the rates have doubled in adults, but sadly, in children and adolescents, those rates have actually quadrupled internationally.

Also, obesity also disproportionately impacts racial and ethnic minority groups. According to the CDC, the prevalence of obesity in adults is 41.7% for the Black population, 38.4% for the American Indian or Native Alaskan, 36% for the Hispanic population and 31% for the white population. It is interesting to note that for the Asian population, it’s only about 11.7%.

We also see that there’s greater gender inequities in obesity. And we call this uncharted territory because we’re learning that females have twice the risk of overweight or having obesity, and they are at much higher risk for developing the comorbidities related to that.

And sadly, they have twice the mortality rate of overweight men.

But I think it’s important to understand what’s the big deal about obesity. And it’s not just that someone’s BMI is higher. It’s the harm that is in the adipose tissue or the fat tissue itself. Adipose tissue is a very, very potent organ of the endocrine system. And we don’t think of it that way like we think of a pancreas, but it is.

And it wasn’t until the mid-1990s, when the hormones leptin and adiponectin were discovered. And we learned that adipose tissue has a high level of that, of the leptin, and low levels of the adiponectin. And so, we began to recognize how important those were as biomarkers in predicting outcomes for cardiovascular diseases.

And again, it’s not just the adipose tissue or the fat that’s the problem. It’s location, location, location. So, where that adipose tissue is located throughout the body. So, some is in really close proximity to organs and can cause damage to those organs like the adipose tissue that’s around the heart and also the retroperitoneal fat or the fat that’s behind in the belly that can encapsulate the kidney and actually invade the kidney itself.

And so, for this reason, we don’t just look at the BMI. We also look at where that fat is. And we can define it by other measurements as well, specifically waist circumference. So, we would see women with a ≥ 35” waist, or men with a ≥ 40” waist.

And again, it’s not just the location, but it’s also the composition on a cellular level in this adipose tissue that’s different and it has different functions. About 90% of our adipose tissue is below the skin, the subcutaneous fat. But 10% of it, typically, is the visceral fat or that fat that is really, it’s behind the abdominal muscle wall itself and it fills the space in the abdomen between the organs.

So that is the most dangerous. And that’s what we blame the chronic conditions on, including the cardiovascular and renal kidney condition diseases.

The large studies show, again, that women with the larger waist have more than double the risk of developing heart disease, even after you adjust for other risk factors such as hypertension, high lipids, and smoking. And even in healthy, non-smoking women, for every 2” of additional waist size, the risk of these diseases, the cardiovascular diseases, go up 10%. So, you can do the math for every 2”. I prefer, personally, not to do the math. It’s kind of scary.

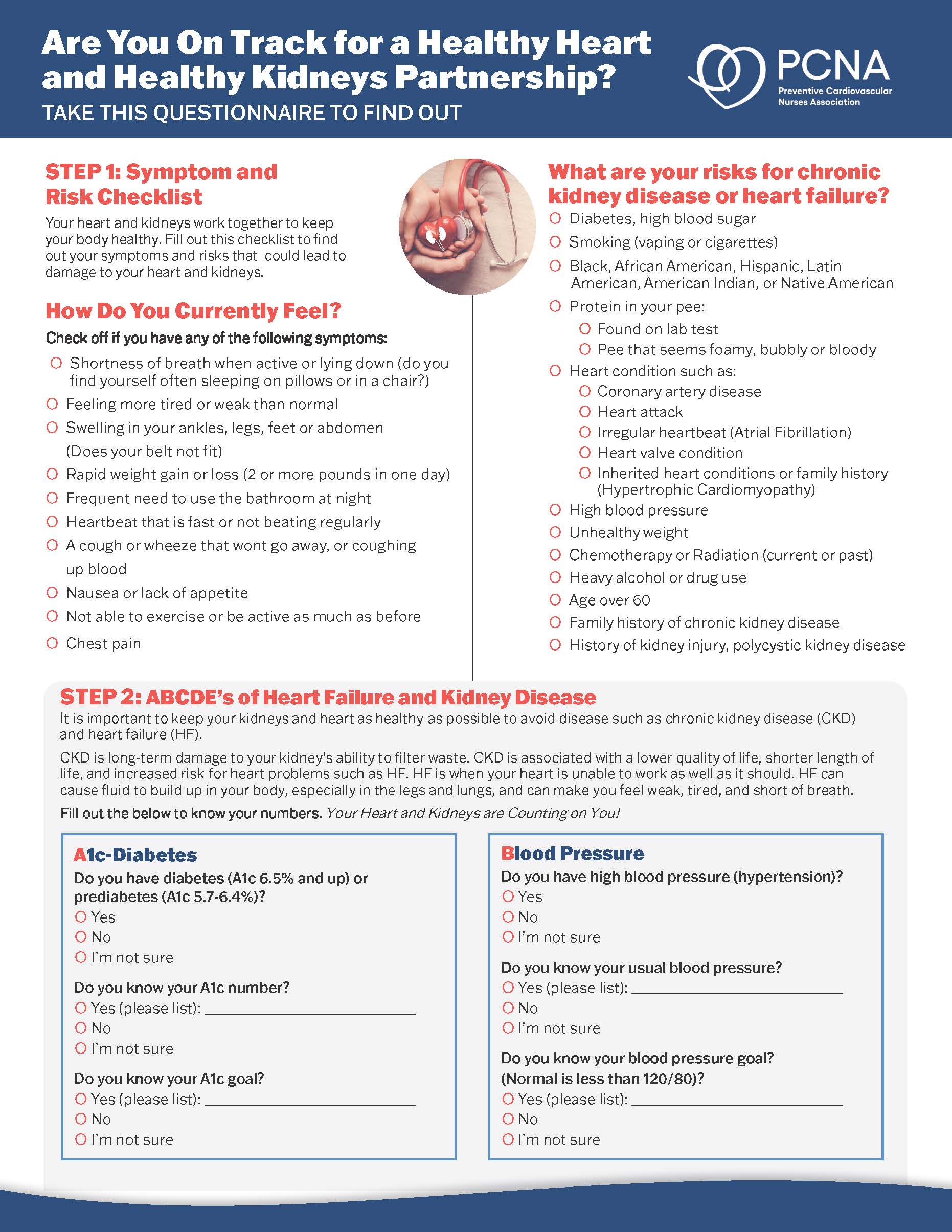

But we also know that that higher volume of that visceral kind of fat has again, not just the risk factors for heart disease, but high blood pressure, blood sugar levels, triglyceride levels, and that metabolic syndrome that we’re talking to.

So, we can talk about obesity and how it affects hypertension. There are several factors that relate to that. In the brain, there’s higher activity because of that increased leptin that I mentioned before, and an increase in the chemoreceptor activations in the heart. There’s a decrease in what we call the natriuretic peptides in the adrenal glands.

So, we can see that that hypertension and other problems with obesity really can affect so many of the organs in so many different ways.

I do want to mention specifically the kidneys. And that is, in the kidneys in patients with obesity, there’s a higher reabsorption of salt. And so that can increase the renin secretion, which leads to further hypertension that just makes this a cyclical thing. And also in the kidney, we see sometimes where it’s called a fatty kidney where it’s defined by so much more fat that has accumulated, that visceral fat has accumulated in the kidneys itself to the point that the tissues are affected and the function of the kidney is impaired by that.

And part of that is the physical pressure on that, on the vascular and the structural components of the kidney that can really lead to changes in how that, how it works. So that’s obesity and kidney diseases.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (09:39)

Anita, thank you so much for taking the time to level set for us information about obesity and how it really impacts all of our body’s symptoms, all of our body’s systems, I should say.

And I know that the treatment of obesity has changed dramatically over time, but would you be able to address for us maybe starting off with lifestyle modifications and how that actually can impact obesity?

Anita Rich (guest): (10:02)

Absolutely. Lifestyle modifications are certainly important in dealing with obesity, especially with the visceral fat that we’ve mentioned. The steps are the same steps that we hear so many times:

Exercise at least 30 minutes a day at a moderate level of intensity and include strength training.

Also, eating a balanced diet to avoid sweetened foods and beverages.

Don’t smoke because this increases your risk of storing that visceral abdominal fat.

Get enough sleep. So, ideally, over five hours of sleep because we’re learning that less sleep, your body significantly accumulates this visceral fat at a higher rate.

And for those that are considering some sort of quick fix like liposuction, that does not address the visceral fat that is really what’s doing the damage.

And so, unfortunately, based on the JACC guidelines, they are noting that all this work, all this lifestyle modification does not really add up to a lot of success. It shows about 5% improvement in triglycerides, blood sugars, fasting blood sugars, blood pressure, incidence of diabetes.

So, what else can we do? And when should that be initiated?

According to the 2025 ACC Concise Clinical Guidance on Medical Weight Management and Optimization of Cardiac Health—how’s that for a long title?—patients should not be started on the “Try, see how you do and come back.”

Similarly to if someone is initially diagnosed with diabetes, we don’t send people home anymore and say, “Try these lifestyle modifications and then we’ll come back and see how you’re doing.” They start medications right away for that, per those guidelines.

So, we do talk about, and we do say, yes, all those lifestyle modifications are very important and they should always be recommended but also in conjunction with these medications that are called nutrient-stimulated hormone therapies or NuSH.

And NuSH therapy helps to address the disease mechanism of obesity. And it targets those hormonal pathways that control appetite, hunger, satiety. And the newest generation of these medications are now being considered even more for cardiovascular disease and kidney disease.

So, I’ll just speak a little bit more specifically to them. There are two main types of medications. These are called glucagon-like peptide-1, or commonly referred to as GLP-1s.

And then the other one is called the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide or GIP.

Thank goodness for acronyms and abbreviations. So exactly how do these work?

So, the GLP-1 receptor agonists have a single action where they work. These are called: liraglutide is one of them, and also semaglutide. And so how these work, the mechanism of action—and remember that an agonist drug binds to that cell’s receptor and activates it like a key in a lock, like insulin in a lock, if you will, a neurotransmitter that produces that response.

So, it regulates blood glucose by stimulating insulin secretion in response to glucose levels. It slows the speed at which the stomach empties and so you feel fuller longer so that increases your satiety.

The other one is a dual action and that’s the GLP-1 in addition to the GIP and that’s called tirzepatide. And that mechanism of action is what we mentioned before. It also stimulates the glucose-dependent insulin to be secreted in response to food. It also regulates the energy balance, signaling the brain to suppress the appetite, and it modifies the lipid metabolism that is occurring in the adipose tissue.

These are the recommendations. And of course, are financial, significant financial considerations with these medications at this time. And there certainly needs to be a lot of interdisciplinary team approach, and considerations and clear communication with the patient and their desires and also discussion of side effects as well, which there are some.

The GLP-1, the liraglutide, has been shown to reduce weight by about 8%. The semaglutide by about

15%. The tirzepatide has been shown to reduce weight by 21%, sometimes even higher.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (15:22)

Thank you so much, Anita, for giving us that amazing rundown of obesity, how it’s diagnosed, what we could do to treat that, and for letting us know that there are some options out there for our patients who are facing this.

We are going to, as I said earlier, put information into the show notes. So, if you have questions about any of the things that have been discussed thus far, look in the show notes and we’ll have some resources there so you don’t have to have this all memorized by the time we’re done with this particular episode.

With that, we’re going to take a quick break and we will be right back.

Geralyn Warfield (host):

We are back to continue our conversation about CKM syndrome and what it looks like in actuality.

Anita covered a lot of great information and guidelines-based kind of conversation for us earlier, but we’re going to turn now to our patient expert here and learn a little bit more about what her journey has been like. So, Jane, could you tell us a little bit more about what your journey has been like?

Jane DeMeis (guest): (16:18)

Okay, first of all, I am a person of size. I’ve always been a person of size. I was born a person of size. And it never, never bothered me at all. It wasn’t a problem to me to be larger than most of my friends, It never bothered me that much.

But as I got older and I was actually teaching at the time and I kind of danced in my classroom and get around, I was also playing tennis almost five days a week.

And I started to have really bad pain in my joints and my knees and my feet and stuff. So, I went to the doctor and I said, “I’m starting to get this pain. I don’t know what it’s from.”

And she looked at me and said, “Truthfully, I’m telling you the truth on this, Jane, you’re fat. Lose weight. You won’t have this problem.”

And I was like, “Okay.”

She says, “In the meantime to adjust to the pain, take 1800 milligrams of ibuprofen daily.”

You should be making a face.

So, this went on for three years as much as I tried to lose weight naturally. I mean I was swimming, I was hiking, I was biking, I was at a swimming pool in my backyard for crying out loud, playing tennis. It was not like I was sitting on the couch eating bonbons. And I just was not losing the weight and the joints were getting worse and worse.

And finally, they diagnosed me. She had blood work done. She didn’t…my rheumatologist had blood work done, and the kidneys had crashed. So that was the beginning of my kidney journey.

Now they rebounded to a GFR 41, which is not great, but it’s livable. It sort of hovered there for quite some time. In the meantime, because of some of the drugs that I was put on, including steroids, my weight increased almost to 300 pounds.

So, I was dealing with that and all of this going on and it was just very frightening.

And I do want to encourage our listening audience that we don’t choose to be obese. Matter of fact, I hate that word. I’d rather be called a person of size. I’d rather be called fat than obese because the connotation of that is you cause that.

And I encourage anybody who is a clinician to keep that in your head. We don’t cause this. Some of us don’t have good diets but some of us have phenomenal diets, like me.

So, I progressed. And then, eventually, in 2018, I retired from my job. I was the Director of Education for a visiting nurse service here. And I decided I got to take care of me instead of patients and families.

And the doctor told me, “You’re going to be on dialysis in six months.”

And I looked at them and I said, “No, I’m not. No, I’m not.”

And I really say the reason why I’m successful is I saw a renal dietitian, not a CDC, a renal dietitian who put me on a diet that I could live with. And I did. And I lost significant weight. I lost about 50 pounds. Couple of years, took time to do it.

CKD. Kept crashing. As we all know, it can be very progressive. And so, eventually what happened was I started to gain the weight. I mean, when people are, yo-yo dieters, that you lose the weight, you gain the weight.

And so, I did end up on dialysis. And now dialysis is a lot of fun because it takes a lot of courage. I do it myself at home. So, there’s a lot of stress with it, and stress is a real trigger for people who are trying to fight their weight.

So, I went for evaluation actually almost five years ago for getting a transplant, which is again the ultimate goal of anybody who’s on dialysis. And they looked at me and again they did the squishy squishy of the belly and said, “You’re kind of heavy,” and stuff.

Continued to get my weight back down and it got to a point which is what happens when you’ve been dieting almost your whole life, going up and down: you get to a point and you plateau.

So, they recommended that I actually do bariatric surgery Which I was not really excited about doing. So, I did do it. I lost another 25 pounds, but the point was—and it was fascinating to hear you talk about the distribution of the tissues—a lot of it was on my abdomen. And that was what they were concerned with.

So, through exercise and proper eating, and when I tell you I’ve been on a diet for eight years, I really have been on diet for eight years, I actually log my food every day. I did lose the 25 pounds, which was not really a great amount of weight.

But the thing is, I lost the belly fat. I also lost my boobs, but it’s part of it, you know? And so, when I went in for an evaluation back in April, the guy did the squishy squishy and he goes, “You’re good to go.” So that was really, really exciting.

Yeah, so I am on the transplant list and actually had the call. So that was exciting until they said the kidney was no good, not mine, the one that they were going to give me.

It is important as a kidney patient to understand you did not cause this. Don’t ever let a clinician make you feel guilty. You’ve got enough to deal with.

Learn that there are ways that you can change. I was on a weight loss drug for a while. At one point, my diabetes was out of control. Long ago, it was in reaction to everything that was going on. It came down but it didn’t come all the way down.

So, they put me on a weight loss drug that also helps diabetes. And then I got rid of the diabetes. I don’t have diabetes. I haven’t had diabetes for four years. My A1C is between 5.2 and 5.4. Again, that has a lot to do with diet. Now, do I treat myself? Absolutely. Life’s too short. But in the same vein, what is your goal? What is it you want to do?

You can’t cure kidney disease. You can stop it. I stopped it for six years. Remember the doctor said you were going to be on dialysis in six months. It was six years before I went on, and that was my choice because I wanted to protect my kidney and my body and my heart; they’re all connected. So, I went on dialysis hoping that that would, you know, keep me safe. So that’s my story.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (23:37)

Jane, I am so grateful to you for your honest assessment of how you were feeling, how you were treated, whether or not the treatment worked or not.

I think if we had been having this conversation 30 years ago, there probably would have been even more blame felt by you as a patient that, you know, why aren’t you just controlling your eating? But we have come a very long way in a very short amount of time in terms of understanding what the mechanisms of obesity are and that it is not a shortcoming of the patient by any standard that this happens.

But that combination that Anita described of lifestyle, honestly, tenacity, and that having the wherewithal to know what you want as a patient and describing that and working with your healthcare team is so important so that you’re all going towards the same goal.

And I think you are a true testament to that shared decision-making and what’s important to you and making sure that you are getting the treatment that you need at the time when it makes the most sense for you. So, I am so incredibly grateful to you for sharing that story with us.

Jane DeMeis (guest): (24:43)

Sure. I’ve always used the sentence that “I am the captain of my ship.” Everybody else rows, but I’m the captain.

Anita Rich (guest): (24:52)

I like that a lot. And as you were talking, I was thinking about what I try to do when I talk to nurses about talking to patients. And I appreciate your sharing with me about even just the use of the word obesity. So, thinking of the words that don’t have that label or have that connotation in any way. And I want the nurses that I talk to—and myself included—to always, first of all, just be kind, be nice.

Think about how you’re talking to someone. Because as soon as that physician said to you, you know, what they said to you, you shut down. And I’ve seen that. And so, if we want to have good relationships with our patients, and our friends and family, I think it’s so important that we just start out really kind and very thoughtful, but especially knowledgeable.

You know, nurses are the most trusted profession and for a reason.

And I’m pretty proud of that. But I think that if in order for people to trust us, we have to be really knowledgeable. We need to be up-to-date on this information. We need to be up-to-date on the guidelines. What are the medications that are available? We need to know what those are. So, I’m so happy to be a part of this podcast.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (26:23)

I have one more question for each of you before we wrap everything up today and Jane, I’m going to start with you.

What one thing do you wish people knew or understood about this particular complicated disease pattern of CKM syndrome? What would you want people to know?

Jane DeMeis (guest): (26:43)

Everything is connected. You don’t have a kidney that’s separate. You don’t have a heart separate. They’re all very, very much connected. And when you’re having an issue with one organ system, I’ll call it that, it impacts the whole body completely. So, if you don’t want to have a heart attack and you’re just like, “Well, I have a little kidney issue.” They’re connected. You really have to be careful.

And as we’re learning in this podcast, weight also has an impact. And it’s not just, you know, get on the scale and how much do you weigh? It’s like, where is the weight and where is the fat and what can you do to lose it?

And if you can’t lose it on your own, then to be able to reach out for help from your healthcare team to support your efforts without making you feel guilty about it.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (27:35)

Anita, what one key takeaway would you have for our audience?

Anita Rich (guest): (27:39)

As the audience is mostly nurses, I think it’s really important to keep in mind what Jane had to say. Her perspective is brilliant, and very insightful.

And I think, as I said before, for nurses to know we need to be knowledgeable about this. We can’t be thinking of things as we learned it in school. And for me, that was a long time ago. And so, we need to move up, update ourselves, with that kind of knowledge.

And I think, too, especially we nurses are everywhere. So, everywhere that nurse has impact with a patient, comes in contact with a patient—and I would say even prioritize primary care, where you’re just beginning to do screenings and blood sugars and blood pressures and that sort of thing, I think a good takeaway and again from what Jane said from the beginning of her story, is to really keep this in mind, be up-to-date with your information. And also, where we can intervene as early as possible with patients.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (28:47)

Again, I am so eternally grateful to you both for being here with us on today’s episode and sharing your stories and sharing the information about CKM so that we can all be a little bit more knowledgeable, be a little bit more compassionate, and be our own captains of our own ships when that becomes necessary as well. That was a great analogy. I appreciated that as well.

I’m going to remind our audience that this is again a third episode in a three arc mini-series about this particular topic, so I encourage you to listen or watch those other topics, or you can check out the show notes for more details in terms of information that you might need and be able to apply in practice.

I’d also like to thank our guests so very much for sharing their expertise with us, and also to Novo Nordisk for their support of this episode.

This is your host, Geralyn Warfield, and we will see you next time.

Thank you for listening to Heart to Heart Nurses. Visit pcna.net for clinical resources, continuing education, and much more.

Topics

- Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

- Diabetes

- Kidney Disease

- Obesity Management

Published on

November 4, 2025

Listen on:

DNP, RN, CHFN, CDCES

Related Resources

Patient Education Handouts

Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome: What You Need to Know

June 26, 2025