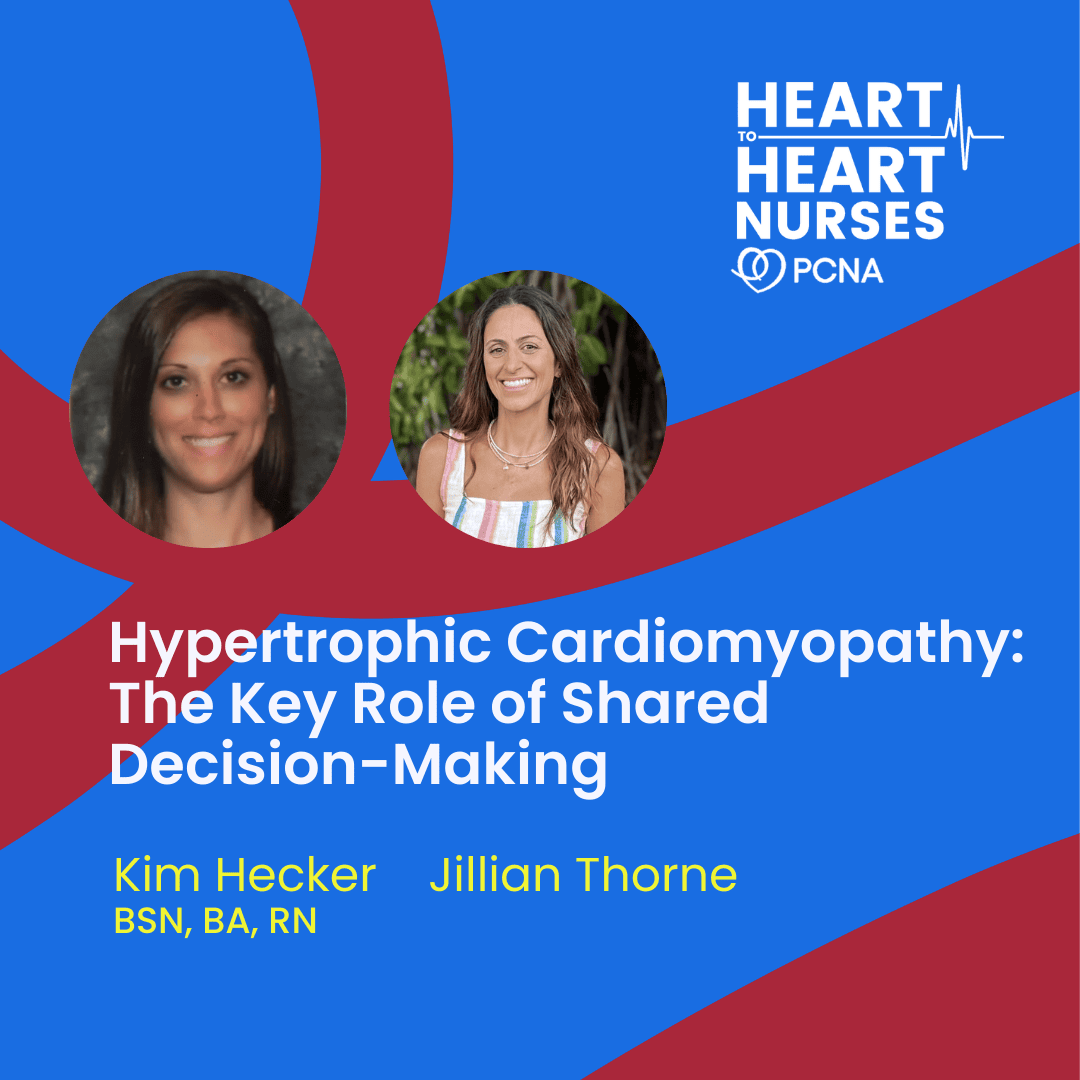

Utilizing shared decision-making in the diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can support positive outcomes for patients, family members, and caregivers. Guests Kim Hecker, BSN, BA, RN, and Jillian Thorne describe the process and the impacts across all stages of the patient journey.

Episode Resources

- 2024 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of HCM

- Twice the Heart Foundation

- PCNA resources on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy for providers and patients

Thank you to Cytokinetics for their support of this episode.

I’m Erin Ferranti, board president for PCNA, and I’d like to welcome you to this episode of the Heart to Heart Nurses Podcast. PCNA is the proud home of cardiovascular nurses and one of the leading figures in the fight against cardiovascular disease. We have the resources you need for your day-to-day practice or to follow your passion to new areas of learning and growth.

Until recently, when a patient was diagnosed with HCM, symptom management was the only therapy available. Now, with two approved treatments–mavacamten and aficamten –shared decision-making is more important than ever to ensure that patients, family members and caregivers understand available treatment options

Geralyn Warfield (host): (00:19)

I’d like to welcome our audience to today’s episode, which is the 2nd of a 3-part mini-series exploring the more human side of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Our previous episode focused on signs, symptoms, and the role of shared decision-making. Today, we’re going to focus specifically on how shared decision-making looks in practice for patients with HCM.

I’m so excited to have our two guests with us today, Jillian Thorne and Kim Hecker. They’re going to be speaking from both the nursing perspective and the patient perspective of HCM. Kim, could you introduce yourself to our audience, please?

Kim Hecker (guest): (00:53)

Hi, thank you, Geralyn. I am so excited to be with you today. Yes, I’m a registered nurse. I’ve worked with the cardiac patient population my whole career. I started in a cardiothoracic ICU focusing on cardiac surgery and transplants. And it was quite overwhelming. And I decided I needed a change, and I wanted to focus more on proactive cardiac health.

So, four years ago, I transitioned into a role as a clinic nurse coordinator focusing on a patient population with cardiomyopathies. And I definitely found a passion here as we use genetics, screening, and prevention as our goal of care.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (01:40)

Well, thank you so very much for being here. Jillian, could you introduce yourself to our audience, please?

Jillian Thorne (guest): (01:45)

Yes, thank you so much, Geralyn. I am Jillian. I am a heart warrior. I was diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy at age 19. I am also the founder of Twice the Heart Foundation. I’ve spent half of my life navigating HCM and now I offer others help as they move through this disease with emotional support, through community, and through real tools to help you feel less alone.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (02:11)

Well, I’m sure our audience recognizes the passion, and the great expertise from both a personal and clinician perspective here. So, I am so excited to have our conversation today.

So, Kim, why don’t you get us started talking just a little bit about what the 2024 HCM guidelines say about the role of shared decision-making in this process.

Kim Hecker (guest): (02:30)

Thank you, absolutely. Yeah, the 2024 HCM guidelines frame shared decision-making as a partnership between the provider and the patient. Making these management decisions around the patient’s goals, maybe what their worries are, their specific preferences, while still understanding the clear options the patient has and the risks and uncertainties that we still don’t know.

There isn’t a single best option for everyone. Every case is different. Every patient is different. Every patient’s life experiences and how they found out about their diagnoses—all this is different. And so, there isn’t a single best option for everyone. There’s not the single best treatment for everyone.

And therefore, these decisions often involve trade-offs. How aggressive should a treatment be? Should a device be used for primary prevention? The shared decision-making creates a confidence between the provider and the patient to make some of these really challenging clinical decisions, and they do prove to have better positive outcomes. This should be the primary communication style. It’s something that my team has focused on, and it’s made a difference in how I treat my patients and how my patients develop a relationship with me.

Certain topics require shared decision-making, or should require shared decision-making, more than others. And these could be such as invasive procedures, risk reduction, advanced therapies for obstructive HCM, could include surgery, ICD implantation for primary prevention. And on top of that, we also have to think of a patient’s family and the discussion around genetic testing and family screening.

Each of these care plans have complex pathways in different directions that they can go. And so, it’s vital for the provider to understand the patient experiences, their concerns, and really building a partnership and trusting long-term relationship with the patients.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (04:59)

I really appreciate how you’ve described the shared decision-making trajectory from the time of diagnosis all the way through treatment and management of these particular health issues and health concerns.

So, Kim, what are some strategies that you use to ensure that the patient feels heard and understood in this process?

Kim Hecker (guest): (05:24)

Yeah, we meet with the patient in a multitude of ways to start. So, the first visit, for example, would be in the clinic with myself and the provider. And maybe that’s the time where they’re getting their diagnosis, or maybe not. Maybe it’s a second opinion, or maybe they are now switching from a cardiologist to an HCM specialty program. And so, from there, that’s where that discussion starts.

But I tend, as my role as the nurse coordinator, I am that liaison between the provider and the patient, making sure that that patient always feels that they have a connection to us, whether that be through phone call, our clinic has nurse-led visits where we can actually do video visits with a patient. Additionally, of course, there’s the availability to My Health message to message your providers, right? And sometimes that message can look like, “Hey, I’m really feeling like I need support from my team right now. Kim, you’re my nurse. Can you reach out to me?”

So, the support is not only supporting the patient in terms of getting their diagnoses, but supporting them through their treatment plan. Maybe we have to make adjustments to medication. Maybe the patient doesn’t want to do that yet, or maybe they’re going on a vacation. How do we work around that? They’re going to go out of town for a month, and yet our plan was to increase medication. That may not work for them now. How do we revise that, and work with the patient?

And, ultimately, the goal is to provide a quality of life for all of our patients. And if that means that we have to change our treatment plan, if that means I need to schedule bi-weekly visits with the patient to keep in touch with them, or maybe they also need to coordinate with our advanced practice providers.

Working as an interdisciplinary team makes a huge difference in all this.

There’s other aspects, too, in terms of do they need a dietician support? Do they need cardiac rehab support? There are so many other levels to this to make sure that we’re really working as an interdisciplinary team, providing the best outcomes in terms of the patient’s whole being, and not just necessarily HCM, even though that might be the reason that they’ve initially come to our team.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (08:22)

Thank you for that expanded answer, Kim. And we are going to take a quick break, and we will be right back.

Geralyn Warfield (host):

I’d like to welcome our audience back to our discussion about HCM and the personal side of that. Before the break, we were talking about shared decision-making and how that process is a little bit different for every single patient and every single situation.

Jillian, I know that as a patient, you’ve got a lot of perspective here, and I’m hoping you can tell us about your journey thus far.

Jillian Thorne (guest): (08:48)

Thank you, Geralyn, and thank you, Kim, for your perspective. It is a different journey than I had, so, it is very refreshing to hear that that is something that is happening at this time.

When I was diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, I was 19. I had my first surgery at 23 and it changed everything.

Instead of relief, I spent years being gaslit about my symptoms Being told it was just simply anxiety. It was something in my head. I just needed to take medication I should not be feeling the way I was feeling. And it took everything out of me.

And so, I spent years struggling, suffering, but I knew something was wrong. And so, I started to doubt myself because every doctor around me who I trusted was telling me that I was okay. I spent years going through depression, massive depression, not just from the illness but from the isolation side, from being, from untrusting your body so much and being told that you actually should not trust your body. I was mourning that trust, mourning my identity, that loss, the belief in my own body.

So, it took me years to rebuild that trust in my body, but it also woke me up. It taught me to advocate for myself. It taught me to believe in myself fiercely. It taught me to listen to myself and create Twice the Heart to be able to help other people.

Navigating the emotional side of this disease is not something that was told about. It was “Take this medication and you’ll be fine.” The emotional part of the journey is just as important as the physical side of the journey.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (10:33)

So, it sounds like, Jillian, that shared decision-making was not really a part of your process when it came to diagnosis or management or treatment decisions. And maybe you could talk a little bit more about that. If so, what worked well, or if not, what might you recommend to the healthcare professionals that are listening or watching to this episode to try and make that transition to shared decision-making and how that might affect you as a patient.

Jillian Thorne (guest): (11:02)

Great question. For years, shared decision-making was not a part of my care. The decisions were made for me, not with me. And that pressure was something that I think is put on providers.

It also shattered my confidence in myself, to advocate in myself because again, I believed in what they were saying.

And so the medicine wasn’t exactly the problem. It was the dynamic. It was the dynamic between the doctors and myself.

I believe that shared decision-making really only works when all sides are being brought in together. It matters just as much as the clinical side of it.

For me, I believe the turning point for me came when I started to ask the questions. And when the physicians and nurses actually started to listen. So, that changed from just what your symptoms are to what are your day-to-day symptoms. They validated my instincts instead of minimizing them. They explained with transparency versus just, “Take this and you’ll be OK.”

They created moments that allowed for hope. They collaborated with me instead of telling me what I should do. I believe when clinicians partnered with me like that, they weren’t hearing my fear, they were just hearing me.

I was able to work with the clinicians and talk about my choices instead of desperately clinging to some answer.That is when shared decision-making really works. When there is equal respect, the clinicians, expertise, and my lived experience.

I believe that for it to really work, there needs to be trust, and we need to start validating with experiences versus clinical data.

I believe that what you’re feeling is real should be a statement that providers share to us. They may not understand it, but they can be there with us in that moment. By saying that, it repairs the damage instead of being medically dismissed. Bringing an emotional impact to the plan, since heart disease is such a mental event. Asking how the patient is coping. Offering choices instead of ultimatums. Offering them to participate in their own life. That goes a long way.

And including caregivers with that in the education, in the decision-making. Because family is important and if you’re living with them that they should have a say in that decision as well.

Being aware of dismissive language really matters. Changing from, “Your symptoms are your symptoms,” to, “Your symptoms matter and we’re still trying to figure out why” leaves a patient leaving that appointment filled with hope and that they are a part of something that they’re living in versus they’re being told and dictated what to do.

Consistency with follow-ups and a treatment plan eventually turns into a partnership.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (14:18)

I so appreciate both of your perspectives from both a patient lived experience, from a healthcare professional expertise and trying to apply that to the situation.

You’ve really demonstrated that healthcare really is a team effort. And that has been a great opportunity for us to learn from both of you how that might apply to our daily lives.

So, I’m wondering if you had one key takeaway in this very important conversation about the human side of HCM, what would that be? And Jillian, maybe I’ll start with you.

Jillian Thorne (guest): 14:50)

Yes, my takeaway is that patients heal best when their lived experience is treated as data, and being believed can change the entire trajectory of care.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (15:05)

And how about you, Kim? What would your key takeaway for our audience be?

Kim Hecker (guest): (15:10)

First, I just want to say, Jillian, thank you so much for, it’s just great for me to hear the experience from your perspective. And to hear how you didn’t have the shared decision-making, which in my career being in this HCM specialty clinic, it’s everything we do every day. And so, I am so, so glad to be talking about this and how important this is.

But yes, my key takeaway is, absolutely, partnership and trust. The provider needs to build that relationship with their patients. It starts there.

And building that relationship has to do with each one of those steps that Jillian talked about: hearing the patient experience, hearing their journey. What is their symptom burden like day to day? How are they living with their symptoms, what is their quality of life? Can they go out for a hike with their best friend and their dog? Or are they stuck at home?

We really need to be able to also provide these patients with the hard truths. Again, we don’t have all the answers. And for some HCM patients, we don’t have great treatments. So, what do we do in those situations?

The provider and the patient really become invested in those trade-offs and really trying to find the thin line of balance between the management options, the patient risks, and the patient’s wishes and their experiences.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (16:50)

We are so incredibly appreciative to both of you for sharing your enthusiasm, for sharing your experience, for sharing your expertise with our audience today. So, thank you both, Kim Hecker and Jillian Thorne, for being with us on today’s episode.

We will put some resources in our show notes, including the links to those 2024 HCM guidelines. So, make sure you look for those.

And also, we encourage you to listen or watch the 1st episode in this miniseries as well as the follow-up episode for even more information.

We’d also like to thank Cytokinetics for their support of this podcast miniseries.

This is your host, Geralyn Warfield, and we will see you next time.

Thank you for listening to Heart to Heart Nurses. Visit PCNA.net for clinical resources, continuing education, and much more.

Topics

- Cardiomyopathy

Published on

February 17, 2026

Listen on:

BSN, BA, RN

Related Resources

Videos

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Infographic: What Every Patient Should Know Animated Video

January 12, 2025