Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common genetic heart disease in the US. Guest James Norton, BSN, RN, shares the hallmark signs and symptoms, and describes shared decision-making in the care of patients with HCM from diverse populations.

Episode Resources

- PCNA HCM resources for providers and patients

- AHA HCM sudden cardiac death risk calculator

- Clinical Course & Management of HCM

- HCM Sudden Cardiac Death Calculator

- 2024 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of HCM

Thank you to Cytokinetics for their support of this episode.

James Norton podcast episode transcript

[00:00:00] I’m Erin Ferranti, board president for PCNA, and I’d like to welcome you to this episode of the Heart to Heart Nurses Podcast. PCNA is the proud home of cardiovascular nurses and one of the leading figures in the fight against cardiovascular disease. We have the resources you need for your day-to-day practice or to follow your passion to new areas of learning and growth.

Until recently, when a patient was diagnosed with HCM, symptom management was the only therapy available. Now, with two approved treatments–mavacamten and aficamten –shared decision-making is more important than ever to ensure that patients, family members and caregivers understand treatment options.

Geralyn Warfield (host): 00:19)

Welcome to today’s episode, which is the first in a 3-part series where we discuss the human side of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. I’d like to introduce our guest to you today. This is James Norton. And James, could you tell us a little bit about yourself, please?

James Norton (guest): (00:33)

Thank you, Geralyn. It’s a real pleasure to be here. Thanks so much for having me on. I’m a nurse coordinator currently at the Center for Inherited Cardiovascular Disease at Stanford Health Care in California. I also serve on the Communications Committee for the PCNA and I’m a lead for the Northern California Chapter.

I started my nursing career in the CVICU and of course, in that setting you’re seeing heart disease at its end stage, seeing the results of poor lifestyle, misdiagnoses, and poor medical management, really when the crisis has already hit.

I realized I wanted to move upstream, to the other side of the equation, where we use genetics and prevention to mitigate these crises before they happen. And that led me to my current role where I now focus entirely on families with genetic heart conditions like HCM, and focus more broadly on the process of improving healthcare delivery through a preventative lens.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (01:31)

Well, thank you so very much for telling us a little bit more about your background, and I’m sure our audience can tell that you have some great breadth of experience in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or HCM. And because our audience might have varying degrees of experience with that, could you make sure that we’re on the same page by maybe describing for us kind of the hallmark signs and symptoms of HCM?

James Norton (guest): (01:53)

Yeah, absolutely. I guess we start with a good diagnostic definition. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a primary genetic disease of the cardiac sarcomere. And that’s characterized by left ventricular wall thickness of 15 mm or greater. We always build a comprehensive family history, and with a verified or highly likely family history, we do drop that threshold to 13 or 14 mm.

And it’s important to note we look for this thickening in the absence of other causes like any infiltrative disease, or severe hypertension, or aortic stenosis.

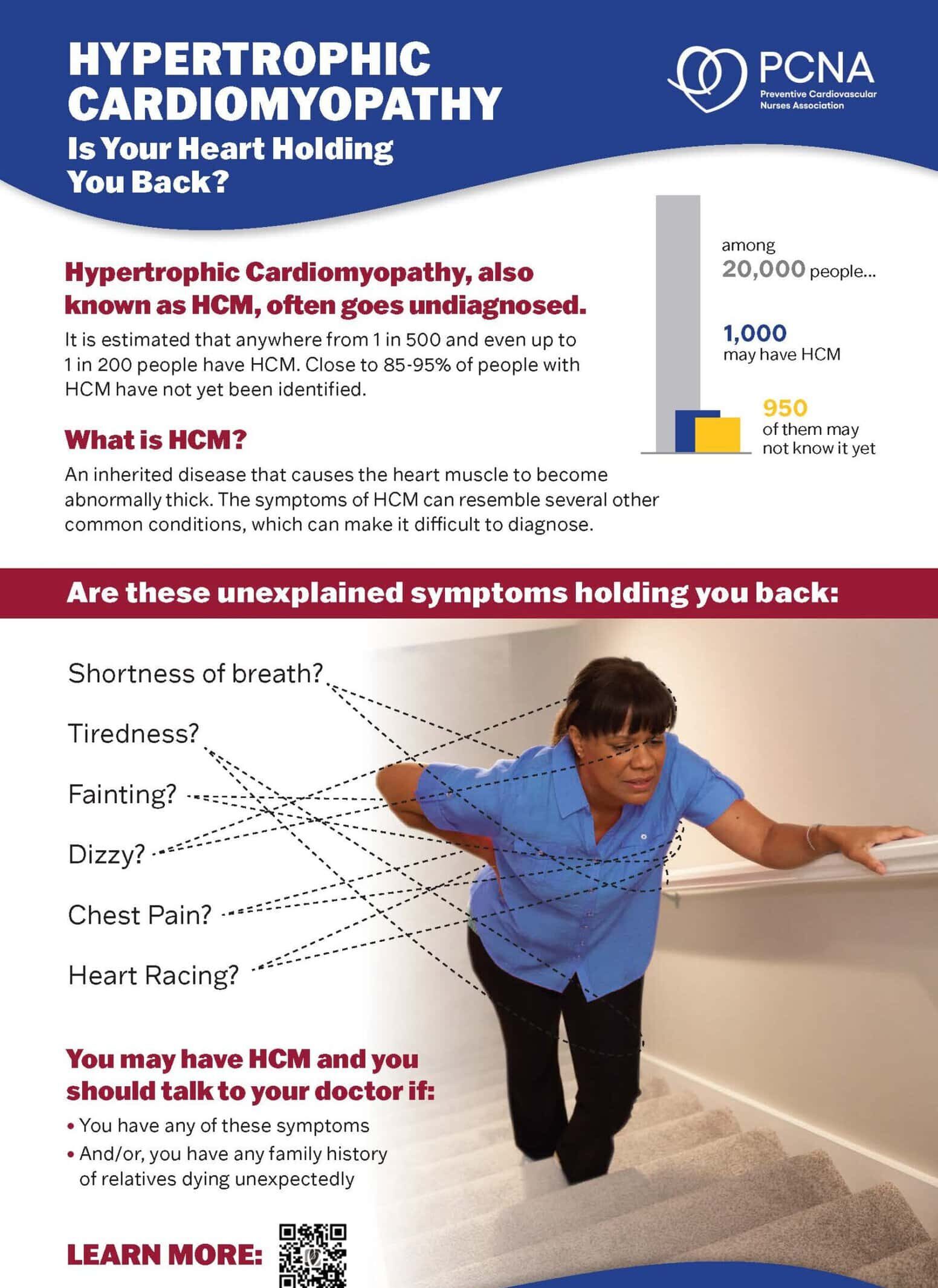

As far as symptoms, patients often complain of shortness of breath with exertion, chest pressure or tightness, and the sensation of palpitations. Some talk about just being tired, fatigued all the time.

It’s important to note, though, that some patients will present symptom-free.

When we evaluate an HCM patient, we really try to look at the whole picture across four different areas. First, we have rhythm. And the EKG is often the first clue because 90-95% of patients are going to present with an abnormal baseline. We look for signs of LV hypertrophy, prominent septal Q waves, deep T wave inversions.

Beyond that, though, we do place a Zio® patch to catch an SVT or atrial fibrillation. The patient often doesn’t feel these runs, but they are major red flags for sudden cardiac death risk. They also give us the ability to quantify their ectopic burden.

The second domain, structure and function, we’re looking primarily for myocardial thickening and often hyperdynamic function on echo. A key stat here for HCM is about 2/3 of patients have left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. One third, roughly, are going to have this at rest, but another 1/3 is going to only have it with provocation. So, we do use exercise/stress echocardiograms to see what the hemodynamics do when the patient is actually working. Because again, I mean, that is often when these gradients present and symptoms start for our patients.

And our third domain here, physical exam, of course, classic HCM murmur is something that we’re always listening for. That’s a harsh systolic crescendo-decrescendo murmur. And that’s from the dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Maneuvers that reduce LV volume, like standing or Valsalva, they bring the ventricular walls closer together, and that worsens obstruction, that’ll intensify the murmur. So, during exam, we’ll often have these patients perform a sit-to-stand, or do the Valsalva maneuver, while listening to see if that worsens the murmur that we’ve detected.

And then finally here, we’ve got cardiac MRI. We use this to look for late gadolinium enhancement, which represents myocardial scarring, and we’ll plug this fibrosis data into the AHA sudden cardiac death risk calculator.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (05:20)

Thank you so very much for going through those continuing-to-change aspects as people are sometimes asymptomatic, and sometimes have symptoms, and sometimes there’s a family history, and sometimes you’re not aware of that. So, it’s really a complex disease to try and diagnose, it sounds like.

And what you said at the very end of your description was about the SCD risk calculator. And I’m hoping you could talk a little bit more about that for our audience.

James Norton (guest): (05:48)

Yeah, great question. So that’s a tool that you can find on the American Heart Association website—now, there’s some variations of the tool that you can find elsewhere on the internet, from European Society of Cardiology as an example. It’s built on a massive foundation of data, and it really allows us, it allows providers to give patients a precise calculation based on everything that we’ve learned about HCM of their risk for sudden cardiac death.

Practically speaking, it’s this validated clinical tool where you’ll input specific variables; that includes family history, history of unexplained syncope, echo measurements, and that critical MRI fibrosis data that I mentioned. And that generates a five-year personalized probability of sudden cardiac death.

In conversations with families, this can bring a lot of clarity. If the risk is low, typically less than 4%, we can offer reassurance that’s really data-backed. If the risk is high, generally 6% or higher, we have a clear protective strategy by recommending an ICD. And in the gray area between those two, that’s where shared decision-making really shines.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (07:06)

And would you, in that gray area that you’ve just described, would you use that SCD risk calculator frequently, meaning every few years, or is it a one-time-and-it’s-done kind of risk calculator that you would use in that situation?

James Norton (guest): (07:21)

Yeah, especially if it’s in the gray area, we would re-evaluate risk on an ongoing basis. Basically, anytime we had new data that would alter those measurements in that initial calculation, whether that was worsening fibrosis, thickening of the ventricular walls, we would go back again to recalculate.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (07:42)

Thanks so much for that clarification. I appreciate it. We are going to take a quick break, and we will be right back.

Geralyn Warfield (host):

We are back speaking with James Norton about hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and what that looks like for our patients. And you mentioned right before we took our break, James, about shared decision-making. And based on the fact that this is a complex disease, what does this look like in clinical practice?

James Norton (guest): (08:04)

It’s a great question and it’s really, really central to the way that we operate. In fact, the 2024 AHA guidelines explicitly call out shared decision-making and say it should be a collaborative dialogue with the patient. I say it takes a village.

We sort of, at Stanford, have these multidisciplinary care pods with the patient being at the center. That starts with our specialty patient flow coordinators, our specially trained medical assistants.

Then we have genetic cardiologists, electrophysiologists, and our advanced practice providers, which at our center are comprised of nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists. They will handle the diagnostic complexity and building the overall care plan.

Then we have our genetic counselors. They lead family screening, and they unearth insights from the genetic testing, which will help guide that care plan.

We have our exercise physiologists. They provide us that functional safety data with the stress testing.

And then I like to think that the bridge that connects all of these is the nurse coordinator. If we consider the dynamic in the ICU, the MD team rounds twice a day, but for the other 23 or so hours, the nurses are there on the floor, titrating, adjusting mechanical circulatory support devices, driving the hemodynamics and the full care plan based on protocol.

And we’ve essentially brought that top-of-scope autonomy into the outpatient setting with our nurses running independent RN-led telehealth clinic. While our physicians focus on research, the overall plan, and the complex diagnostics, we sort of step in to manage the day-to-day care and be the primary point of contact for our patient population. And just like in the unit, we use protocols to autonomously manage everything from titrating GDMT to newer cardiac myosin inhibitors and even GLP-1 medications.

We partner with Stanford’s innovation team to use AI to surface EHR data and draft patient messages. And that automation is helping clear the admin sort of clutter, so to speak, and allow us to focus on the patient.

We use the visits to perform deeper education, review test results, and provide sort of holistic, preventative lifestyle coaching and exercise guidance. Overall, shared decision-making, we cultivate this family atmosphere where patients know us by name, we know them, and hopefully they feel truly heard.

Every decision, whether it’s a test result, or a med change, is framed so that the patient is the main voice in the room and the active core of their care plan.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (11:04)

When you’re talking about working with diverse populations, are there any specific considerations to keep in mind when applying the strategy of shared decision-making with those groups?

James Norton (guest): (11:14)

Yeah, yeah, definitely. I think the foundation, of course, of every relationship is getting to know the patient: who they are, what drives them, what their barriers are. I think that’s really the only way that you can build a care plan that works.

But beyond the individual, we do look at the whole context. And living here in Silicon Valley, we serve this massive paradox where you have some of the wealthiest people in the world, some of these tech execs, living in the same town as service workers who are struggling to make ends meet. Because of that, there’s definitely no one-size-fits-all approach for HCM care.

In our weekly huddles, this comes up a lot. We talk about the concept of structural competency and the social determinants of health. It’s this realization that even in a genetic condition like hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a patient’s health outcomes are often dictated more by their zip code than their genetic code.

And so, we do have some specific strategies to address this. First, we shift from sort of broad health literacy to visual literacy. Instead of showing grainy echo images to patients that don’t have strong health literacy, we use clear annotated diagrams to map out their own anatomy: where the wall’s thick, where the obstruction might be. And I feel that turns sort of a scary diagnosis into a more mechanical problem that’s easier to grasp.

And we’ll do the same thing for rhythm, using the Zio® timeline so they can see when pauses occurred, or when they had runs of an SVT, and connect them to symptoms that they were feeling at the time.

And I think, just as important, we try to act overall, for all of our patients, as system navigators. Our US healthcare system is, of course, so complicated, maze-like. We think of ourselves as sort of air traffic controllers. We follow up on referrals to other departments, coordinate between specialties, and we don’t just prescribe a medication. We investigate those social determinants of health.

If a patient can’t afford gas to get to the clinic, or if their insurance denies a cardiac myosin inhibitor, we step in. We use robust appeal protocols and our social work connections to do everything we possibly can to dismantle those barriers for our patients.

And I think third is just operating with cultural humility at all times, really trying to meet the patient where they are. We recognize that in some communities, there’s a real deep mistrust of the healthcare system or significant stigma around genetic testing. So rather than trying to “correct beliefs,” we focus on understanding the behavior and the fear behind it. We collaborate with our genetic counselors to listen and validate. And that really helps us explain things in the context of their worldview rather than challenging it.

And ultimately the goal is to ensure, whether you’re a CEO or a farm worker, the moment you walk through the door, you’re getting the exact same level of care as the next person, tailored specifically to you and your reality.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (14:50)

I am very grateful to you for taking that worldview that you do for these patients because this can definitely be something that impacts not just today, but every day moving forward when they get that diagnosis. And so having that team of individuals who are there to support, and listen, and to help the patients understand what’s going on, what the options are, and making them the center of that decision-making is really critical.

So, I want to commend you and your team for all the effort that goes in because this is not an easy checklist that you can just, you know, talk to them about that, done. It’s an ongoing communication structure and I really appreciate the fact that you bring them into the fold, literally, and work together towards those next steps for them.

So, we have covered a lot of ground today and if I asked you what your one key takeaway would be for our audience, what would that be for you?

James Norton (guest): (15:44)

Yeah, you know, Geralyn, I feel like we’re sort of entering a golden age right now, so to speak, for the awareness and the treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. We have this sort of confluence of things happening as AI integrates into our testing to improve precision, and access, and interpretation.

We have all these new novel precision therapies coming to market with the cardiac myosin inhibitors.

I think the entire landscape’s really changing for HCM and this will allow us to further deploy the proactive care model that we discussed today, hopefully shifting from this reactive stance to a fully preventative one.

And in this environment, I think the role of the cardiovascular nurse is going to expand exponentially. We’re really the touch point for the patient with their care team. We’re the ones who translate all these advanced therapeutics and testing, or pass down our understanding of this complex condition in a way that meets each and every patient where they are.

We’re the ones who are there to make sure no one falls through the cracks. And I think that’s how we build this population, every HCM patient, a roadmap to a long, normal and happy life.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (17:05)

James, thank you so very much for sharing your expertise and your insights with us today.

As I mentioned to our audience at the top of our recording, we are doing a 3-part mini-series on this podcast topic of HCM and the human side of that particular disease, and if you are interested in more information, I encourage you to listen or watch the next two episodes in this series, and also to check out the show notes for any resources and additional materials that might help you in your work each and every day with patients with HCM.

We’d really like to thank Cytokinetics for their support of this mini-series.

This is your host, Geralyn Warfield, and we will see you next time

Thank you for listening to Heart to Heart Nurses. Visit PCNA.net for clinical resources, continuing education, and much more.

Topics

- Cardiomyopathy

Published on

January 26, 2026

Listen on:

BSN, RN

Related Resources

Videos

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Partnerships: Primary Care and Centers of Excellence Video

January 19, 2025

Patient Education Handouts

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Is Your Heart Holding You Back? Poster

September 08, 2025