Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome is progressive, but can be halted or even reversed with effective management. Guests Chiadi Ndumele, MD, PhD, and Joe Saseen, PharmD, BCPS, BCACP, describe the role of inflammation and how the biologic factors for diagnosis and treatment are nested within a patient’s social context.

Episode Resources

- 2023 AHA Statement Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health

- PCNA CKM tools and resources

- AHA Cardiovascular Kidney Metabolic Health Presidential Advisory

- AHA CKM Syndrome Implementation Guide

- PCNA CKM resource list

Thank you to Novo Nordisk for their support of this episode.

[00:00:00] I’m Erin Ferranti, board president for PCNA, and I’d like to welcome you to this episode of the Heart to Heart Nurses Podcast. PCNA is the proud home of cardiovascular nurses and one of the leading figures in the fight against cardiovascular disease. We have the resources you need for your day-to-day practice or to follow your passion to new areas of learning and growth.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (00:19)

I would like to welcome our audience to today’s episode where we are going to be focused on CKM syndrome. We’re going to talk in just a moment about what that means. First of all, I’d like our guests to introduce themselves. So Chiadi Ndumele, would you please introduce yourself to our audience?

Chiadi Ndumele (guest): (00:34)

Thank you so much, Geralyn. It’s really wonderful to be here. I’m Chadi Ndumele. I’m a cardiologist, preventive cardiologist and epidemiologist. I am the Director of Obesity and Cardiometabolic Research at Johns Hopkins University in the Division of Cardiology. And then I also am the Chair of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health for the American Heart Association, and the Chair of the CKM Health Initiative for American Heart and was also the Chair of the Scientific—well actually the Presidential Advisory—on CKM Health, and it’s great to be here.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (01:08)

We’re so glad to have you here and you are joined by Joe Saseen. Joe, could you introduce yourself, please?

Joe Saseen (guest): (01:13)

Certainly, thank you for having me. My name is Joe Saseen. I’m a clinical pharmacist. I’m currently Associate Dean for Clinical Affairs and a Professor at the University of Colorado, Skaggs School of Pharmacy on the Anschutz Medical Campus. I also am a Past President of the National Lipid Association and I’m currently a member of the guideline writing committee for the upcoming dyslipidemia guideline from ACC and AHA.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (01:40)

Well, I’m sure our audience can tell that we have a great deal of expertise on this particular episode. So, we’re going to go ahead and get started with our topic of CKM syndrome. And CKM stands for cardio-kidney-metabolic syndrome. And Joe, maybe you could level set us and help us understand a little bit more about how this designation came about.

Joe Saseen (guest): (01:59)

Sure. It came about, the simple answer is in 2023 there was an AHA scientific statement which really framed this syndrome, the cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic, or CKM, syndrome.

And I think if we just take a step back in time, we’ve heard about components of this in the past. We’ve heard of the metabolic syndrome, which has evolved to—sometimes people call it the deadly quartet.

And now we actually are living with CKM syndrome, which really is an effort by the American Heart Association, in my opinion, to harmonize a lot of things that interplay with each other. Because when we approach patients that have CKM syndrome, we’re identifying patients that have a multitude of diseases.

And it’s not just cardiovascular. It also involves the kidney system and metabolic abnormalities. And it’s not just diabetes. We have an appreciation for how everything from obesity to kidney health and kidney decline to cardiovascular risk, ranging from hypertension to dyslipidemia and even hepatic disease, is also a component of this overall syndrome.

So, it is a means to harmonize a lot of different diseases and, I guess, risk factors for progression of disease that have common endpoints which can be cardiovascular, kidney, and/or metabolic endpoints which are harmful to our patients.

It also seeks to harmonize, we have about, more than four different diseases per se with multiple guidelines into really getting clinicians to appreciate that we can’t just treat one disease in isolation. That when we treat one, we may have benefits for other diseases and vice versa.

I think another thing that’s really important, the last thing I’ll say about the CKM syndrome, it also incorporates importance of social determinants of health into the progression of disease amongst our patients who are at risk for these morbidities and mortality associated with CKM syndrome.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (03:56)

Thank you so much, Joe, for that comprehensive overview. And I am just delighted to hear those words, quartet and harmonize. I think that really resonates, if I might continue that, with our audience and with clinicians overall to kind of understand how things interplay together.

And Chiadi, as we’re looking at this multi-system syndrome, what kind of role does inflammation play and how do inflammatory markers come into the diagnosis and management of these patients?

Chiadi Ndumele (guest): (04:23)

Yeah, thank you very much. I think as we’re thinking about this multi-system interplay, it’s really helpful to think about inflammation as one of the central pathophysiologic features that are really connecting all these conditions.

When we start with a lot of the things that Joe mentioned, start with excess and dysfunctional adipose tissue, particularly in the visceral cavity, or in some ectopic spaces like in the liver in particular, we tend to see an inflammatory response related to that. And that can be shown by several cytokines and other acute phase reactants, and other molecules in the blood, things like CRP, TNF-α, a bunch of interleukins.

But what’s important is that that is also linked to the development of insulin resistance because we see a lot of impairment in how insulin signaling works. Insulin is what helps our body, as I’m sure many people know, use glucose. And basically, that process gets impaired by virtue of that inflammation. And over time, as we get more insulin resistance and more burnout from our pancreas, that can actually lead to frank diabetes.

On top of that, we have a lot of other risk factors: metabolic conditions, high blood pressure, the dyslipidemias that Joe mentioned that basically come along with this and go along with inflammation. And then, frankly, chronic kidney disease itself is now recognized as a very inflammatory and also fibrotic process. And so, it really kind of centrally connects all these different pieces.

in addition to the intimate relationship of inflammation with so many of these metabolic risk factors, we also know that inflammation is really directly associated with chronic kidney disease. And various kidney disease we now think of as more of even an inflammatory and fibrotic state.

Additionally, we have something that we think of that makes life hard for clinicians called Cardio-Renal syndrome where the heart and the kidney have a bi-directional relationship. And that’s very challenging both from a prognostic and therapeutic standpoint. And the likelihood of that goes up when you have more systemic inflammation.

So, inflammation is kind of very central to this process.

Then, of course, inflammation is also core to many forms of cardiovascular disease. So, atherosclerosis is a very inflammatory process. Heart failure is now widely kind of appreciated as more and more of an inflammatory process. So, inflammation is really core to the pathophysiology. While CRP is a really useful marker because it’s associated with a higher burden of these various conditions, more metabolic risk factors, more CKD, it’s certainly associated with cardiovascular disease risk as well.

And while we don’t necessarily say that we should measure inflammatory markers for everybody as part of the CKM care model, they are informative. And actually, CRP is one of what we call risk-enhancing factors. Risk-enhancing factors, or risk enhancers, that we look at are either variables—or in this case biomarker—that can tell us something about the likelihood of people progressing along the CKM syndrome stages.

And the CKM stages really reflect a lot of the pathophysiology Joe was talking about earlier, where it starts with excess and dysfunctional adiposity in stage 1, to the development of metabolic risk factors or CKD in stage 2, to subclinical CVD in stage 3, to frank CVD, overt clinical CVD in stage 4.

And as you’re seeing the patient in front of you and wondering, you know, who’s more or less likely to be progressing along those spectrums, CRP is one of those things that can give you additional information to personalize those risk discussions with your patients.

So, I think that that’s one of the roles those inflammatory markers can play as we use them in practice.

Many of the therapies that we use to address CKM syndrome, lifestyle modification with diet and exercise, GLP-1 receptor agonists, or GLP-GIP receptor agonists, to address weight and glycemia and chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease in some circumstances, and certainly fatty liver disease or MASLD.

All of these, we see an anti-inflammatory effects of these therapies and we see the inflammatory markers like CRP going down with those therapies. So, it’s a nice indicator of the effect, the therapeutic effect that we’re seeing with some of these therapies.

Additionally, some of the other agents like statins that Joe talked about, the dyslipidemia piece that’s central to what we think about for addressing risk in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or at risk, and that has a very anti-inflammatory effect as well. As well as some of the other agents like MRAs that we use in this regard.

So, a lot of anti-inflammatory benefits we see that you can tie to inflammatory markers. It can help you understand the pathophysiology, and it could also give you some insight into who’s more or less likely to progress along the spectrum of CKM syndrome.

Joe, do you want to say anything about other things on the horizon since you have our pharmacology expertise?

Joe Saseen (guest): (09:50)

Sure, I mean we know that we have a lot of current therapies as you mentioned. When we do the right thing by managing comorbidities, we often have a positive effect on reducing inflammation, especially with weight management.

But we do have one current drug that’s probably underutilized which is colchicine. It doesn’t have a broad role for overall decrease in inflammation, but for somebody with established coronary disease, maybe there’s a possibility there.

There are on the horizon some newer therapies. And some of these newer therapies are not available right now, but may be used in the future. And they’re really interleukin-6 blockers. So specific drugs that might mitigate that inflammation and reduce cardiovascular risk. And they range from monoclonal antibodies such as ziltivekimab. There’s also one though that’s a brand new one to me. It’s pacibekitug, which is being developed. And we might see those over the next couple of years as an additional treatment for that specific patient where inflammation is, despite managing other comorbidities, still a persistent issue.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (10:54)

We are going to take a quick break and we will be right back.

Geralyn Warfield (host):

We are back to continue our discussion about CKM syndrome with Chiadi Ndumele and Joe Saseen.

And our next segment is really about kind of risk factors and how do you recognize this in clinical settings.

So, Joe, maybe you could get us started talking about what are some of those risk factors. They’re obviously probably pretty numerous, but what are some things we really need to be looking out for?

Joe Saseen (guest): (11:19)

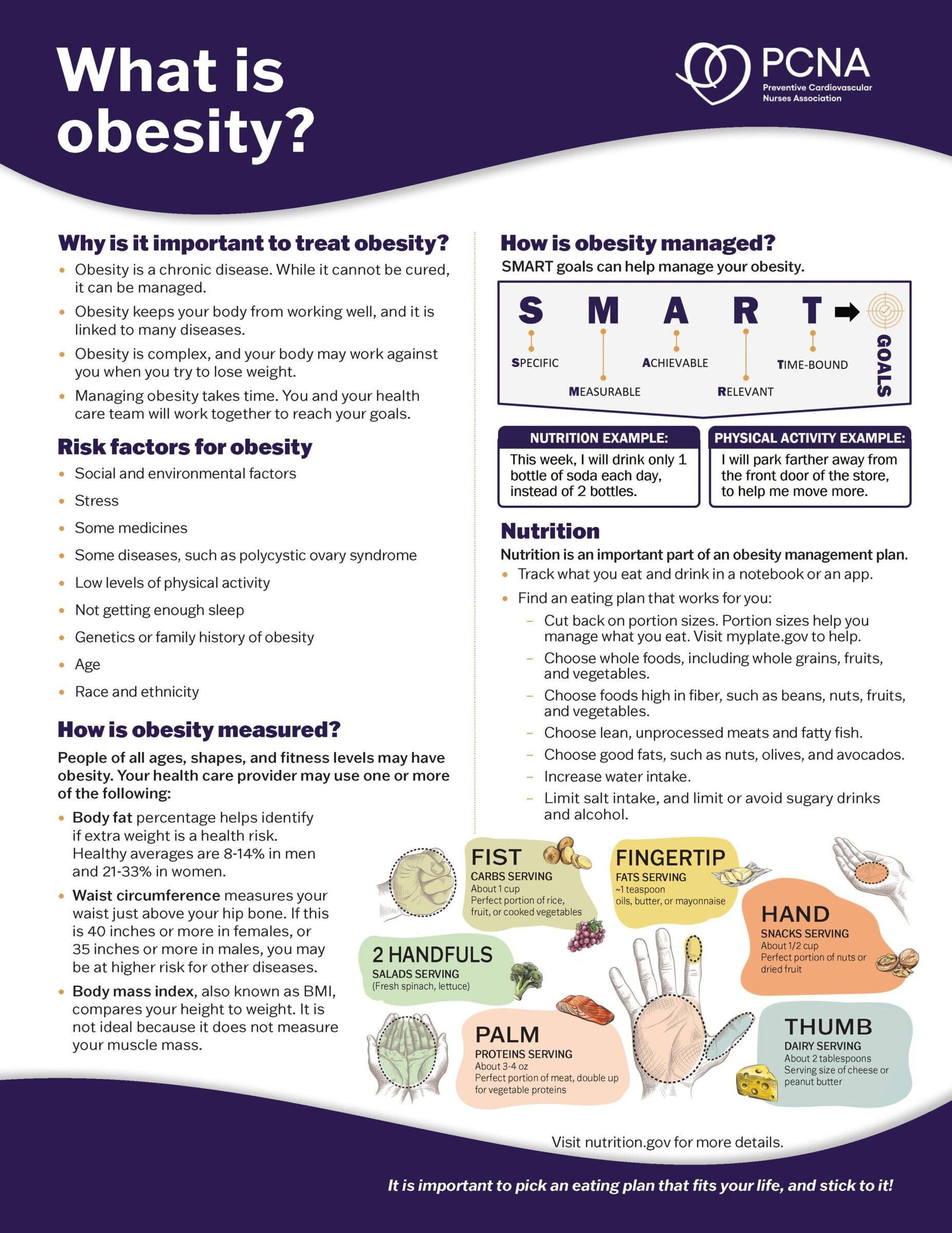

Sure. Some of the things that we can look out for are common and we already have known about these when we first got introduced to the metabolic syndrome. So, patients who have:

Overweight status or who have obesity, that definitely is an underlying risk factor.

Everything else, such as elevated blood pressure—doesn’t even have to be overt hypertension yet, but elevated blood pressure.

Metabolic dyslipidemia profile, where patients have high triglycerides, low HDL.

Other things such as family history of cardiovascular disease definitely is a player as far as elevating individual risk.

Patients with elevated fasting glucose that may not be at the point of diagnostic for diabetes. That also is very important.

So those are traditional things.

You can also throw in their tobacco use, and things that have evolved that we sort of don’t always think about is poor sleeping, dietary indiscretion, which obviously impacts a lot of these other things.

But really layering in some of the other socioeconomic factors into a framework, which is well described in the CKM syndrome AHA statement. Things such as the environment that people live in, their neighborhoods, their access to healthy foods, and to healthcare, also are players which sort of contribute to that population that’s at risk may be having an extra burden of disease.

And Chiadi, what would you add to that?

Chiadi Ndumele (guest): (12:41)

No, I think that that’s a really great list.

I think that one thing I will say is that, well, first of all, you really nicely described the biological factors. And I think it’s important not to consider that and the social factors separately, but rather to think about those biological factors as being kind of nested within your social context.

So, some people are going to have more biological risk than others. And then that’s going to be amplified by being in a circumstance where there’s more multi-level social challenges that make the CKM syndrome progression and complications more likely.

I think there’s some other groups that we know have some interestingly high risk. So, for example, South Asian ethnicity seems to be associated with particularly high risk. And we don’t understand fully why that is the case. There’s a thought that there’s probably some biological and also some social components, but it’s not fully understood.

I think one of the other areas that’s really important to think about is mental health. So mental health is a really important factor that’s associated with, independently with, a lot of these components, but also is associated with how we engage with lifestyle and self-care and the healthcare system.

And then another one I don’t want to miss is, obviously, things like family history and genetics are important to consider in this regard too.

But then there’s some sex-specific factors. So, for example, having challenges with pregnancy, so more adverse pregnancy outcomes like gestational diabetes or preeclampsia, those are ones that are often not recognized but can really cause kind of life course risk. Then, early menopause is another really important one as well that we need to pay attention to.

But I think that list is really great and helpful.

And then I think it also ties into the question of, basically, what the early clinical indicators are. So, we tend to think of things as clinicians. We often put things in categories and we have this in the stages as well. “You now have hypertension,” “You now have diabetes.”

But the reality is, those don’t usually just come out of nowhere if you’re monitoring. Those are usually a bit of a progression, and they happen kind of gradually over time. So, as Joe was mentioning, you’ll start to see those early indicators of hyperglycemia, so early rises in blood pressure, those early changes in your lipids where your triglycerides are going up and your HDL is going down, before you have frank diabetes and frank hypertension and frank metabolic syndrome. So, I think that’s important.

But the other things that we probably don’t pay enough attention to are changes in the liver. And we often can pick that up just with, you know, seeing abnormalities initially on the liver function test, for example. But those are very, very synonymous with CKM syndrome.

And as we know now, this kind of insulin resistance state is the kind of primary cause of what we’re seeing in terms of cryptogenic cirrhosis and the leading cause of liver transplantation now. It’s a major challenge and we know now, with weight loss and GLP-1s and some of the newer therapies, that we can actually reduce that risk. So, recognizing it earlier is helpful.

There’s one of the indices that we look for now for looking for evidence of liver fibrosis called the FIB-4 index that just takes into account your liver function test, your age and your platelets. It’s a very simple test, but it can tell you, hey, there’s a high likelihood here of fibrosis, or a pretty low likelihood of fibrosis in the liver, but you can investigate further.

And then the other one I want to say is about chronic kidney disease. And we tend to look at eGFR, but I think that we miss a lot of people because we’re not looking at urine albumin-creatinine ratio. And that’s one that’s a very inflammatory measure. It’s a big marker of vascular injury, and it’s part of the diagnosis of CKD. So, we’re going to miss a lot of people with chronic kidney disease if we don’t take into account both the estimated glomerular filtration rate as well as a urine albumin-creatinine ratio.

So, I think the big take home there is just to make sure we’re thinking about things on a continuum. And the fact that these abnormalities or these risk factors when they’re established don’t come out of nowhere, they’re a gradual process and we have an opportunity to prevent progression to full-on disease.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (17:05)

My final question for each of you is what one key takeaway would you like our audience to have as a result of listening to us or watching us today? Chiadi, I’ll let you go first.

Chiadi Ndumele (guest): (17:16)

Sure. You know, the big take home I would take here is as we’re thinking about this is understanding that inflammation plays a central role in CKM syndrome. It’s a central driver for most of the pathology that we’re seeing, but it’s also very modifiable.

So, a lot of things that we know, that we can do better with, which is weight reduction, which is lifestyle modification.

And then some of the therapies that are indicated have a significant anti-inflammatory effect. And it’s also possible it can help us understand your likelihood of progressing with CKM syndrome.

So, it’s an important piece. It’s modifiable, and one, as Joe mentioned, that could be a future target for therapies to improve CKM syndrome. We’ll see where that goes.

Geralyn Warfield (host): (18:03)

Joe, how about you? What’s your key takeaway for us?

Joe Saseen (guest): (18:05)

Yeah, I have a comment just on what Chiadi just said. I really love that it starts with weight management or just acknowledgement of the importance of managing obesity or overweight status. And we have medicines that are effective now, on top of lifestyle, which is absolutely effective. So, I really I love your take home Chiadi. It makes me think of that.

My take home would be from a drug therapy standpoint, since I am a pharmacist, is that we have effective treatments once we need them, once a lifestyle has been, I guess, maximized as much as possible.

And we have this concept of ‘two-fers’ you know, when you get two benefits for one drug. I think we need to think of ‘three-fers’ and ‘four-fers’—because there’s a great appreciation now, based on evidence that we have, that treating one of the components of the CKM syndrome often helps, depending on what you’re using, another or more than one other component of CKM syndrome.

So, the holistic treatment, including lifestyle and escalating to medication therapy when needed is really not only needed in a lot of patients, but we’ve also never been better suited to do that than we are currently.

Chiadi Ndumele (guest): (19:12)

Really well said. A lot of bang for your buck with what we know to do well.

Joe Saseen (guest): (19:17)

Bang for your buck. Love it!

Geralyn Warfield (host): (19:19)

I would like to thank both of you for your sharing of your expertise and this awesome overview of CKM syndrome for our audience. Both of you have just shared so many nuggets of great information. I think it was kind of hard for me to pick a takeaway, which is why I asked you about the takeaway at the end. So, thank you so very much for being here.

I’d like to remind our audience this is actually the first of a 3-episode miniseries. And so, if you’re interested in even more information about this, please stay tuned to our next 2 episodes. And you’ll find those on the pcna.net website or wherever you find your podcast episodes.

I’d also, if you wantt information about other resources that you’re seeking, we’ll put information about that in the show notes. So, we’ll put in some links for you there as well.

Again, thank you to Chiadi Ndumele and Joe Saseen for being with us today.

I’d also like to thank Novo Nordisk for their funding for this particular episode.

This is your host, Geraldyn Warfield, and we will look forward to seeing you next time.

Thank you for listening to Heart to Heart Nurses. Visit pcna.net for clinical resources, continuing education, and much more.

Topics

- Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

- Diabetes

- Kidney Disease

- Obesity Management

Published on

November 4, 2025

Listen on:

MD, PhD, MHS

PharmD, FNLA, CLS

Related Resources

- « Previous

- 1

- 2