Diagnosing many cardiovascular diseases requires investigating personal and family histories, being suspicious of certain symptoms, looking into lab results, and diving into data. For many diseases and conditions, including Wellens’ Syndrome, “hidden in plain sight” means that healthcare professionals need to be aware of the possibility of life-threatening anomalies, even in the absence of symptoms.

Wellens’ Syndrome Case Study

A 40-year-old male patient, Mr. Smith, is admitted to his primary care provider’s office after complaining of mid-sternal chest pain that occurred about 12 hours ago. While the pain resolved spontaneously, the patient’s significant other insisted that he seek follow-up care.

The patient has a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, and had smoked for approximately 20 years before quitting about two years ago.

Upon physical examination, the patient now denies chest pain, his vital signs are stable, and the physical examination is unremarkable. While the rest of the laboratory values are normal, there is a slight elevation in troponin I. An EKG is ordered, and based on EKG changes, the physician suspects Wellens’ Syndrome.

Why Worry About Wellens’ Syndrome?

What caused the physician to suspect Wellens’ Syndrome? Wellens’ Syndrome is an EKG pattern that is highly specific for a critical proximal stenosis of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. This syndrome has been described as ‘hidden in plain sight’ as it is often unrecognized—yet it carries a substantial mortality risk.

Early recognition and prompt coronary intervention are essential for these patients, since they do not do well with medical management alone.3

What is Wellens’ Syndrome?

Mead and O’Keefe describe Wellens’ Syndrome as ‘characteristic T-wave abnormalities that are indicative of a proximal LAD occlusion that will soon result in an acute anterior wall myocardial infarction (AMI) if the patient is not urgently catheterized.’

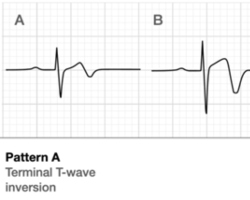

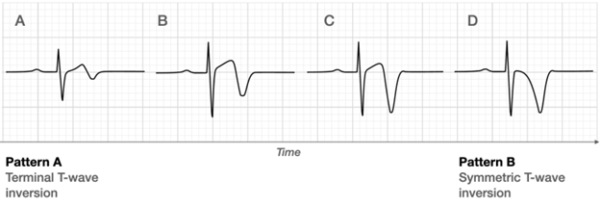

Two T-wave patterns are associated with Wellens’ Syndrome: Type-A T-waves are biphasic with initial positive deflection and terminal negativity in V2-V3. These findings are present in approximately 25% of cases of Wellens’ Syndrome.2 The more common presentation, Type-B T-waves, are deeply inverted and symmetrical in V2-V3, and make up 75% of the cases.2 See Figure 1.5

Figure 1

In addition, the patient would present with less than 1mm of ST elevation, normal R wave progression, and no precordial Q waves.2 A recent history of angina, the EKG pattern noted in a pain-free state, and normal or slightly elevated cardiac biomarkers are also diagnostic.2

The pathophysiology of Wellens’ Syndrome is not precisely known.2 But due to unstable coronary perfusion, patients are at substantial risk of an extensive MI and possibly death.2 One thought is that Wellens’ Syndrome is caused by an atherosclerotic plaque that ruptures and lyses before complete occlusion takes place.2 Others theorize that coronary spasm and stunned myocardium cause the phenomenon, while others note that it may be due to repetitive ischemia and perfusion that leads to myocardial edema.2

Risk Factors for Wellens’ Syndrome

Risk factors for Wellens’ Syndrome are the same as coronary artery disease, including dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, lifestyle, obesity, familial history, smoking, and stress.2 Patients typically have a history of chest pain, tightness, or pressure, often with activity, which subsides with rest. Upon admission to the emergency department or physician’s office, patients are comfortable and pain free, although some may complain of mild distress.2

The Role of Nurses in Diagnosis of Wellens’ Syndrome

Nurses play a vital role in the recognition of this syndrome. Early recognition can lead to prompt coronary catheterization, prevention of anterior wall MIs, and even prevention of death.

In response to the EKG changes, nurses caring for Mr. Smith immediately informed the practitioner. Mr. Smith was then emergently transferred to a PCI-capable hospital where he was urgently taken to the catheterization lab and a 95% occlusion of his proximal LAD was stented.

References

- Al-assaf O, Abdulghani M, Musa A, Aljallaf M. Cases and Traces: Wellens’ Syndrome: The life-threatening diagnosis. Circulation. 2019;140:1851-1852. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA. 119.043780

- Miner B, Grigg WS, Hart EH. Wellens’ Syndrome. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. July 2023.

- Penmetsa M, Rashid W. Hidden in plain sight: Wellens’ Syndrome. A Pattern to remember. Chest. Oct. 2023.

- Mead NE, O’Keefe KP. Wellens’ Syndrome. An ominous EKG pattern. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma and Shock. Sept-Dec. 2009.

- Ecgweekly.com. Figure 1. Wellens’ Pattern A and B.

Published on

August 14, 2025

EdD, MSN, MHA, RN

Related Resources

Sorry, we couldn't find any resources.