While levels of Lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)) are genetically determined and relatively stable over time, Lp(a) can increase with age and with acute illness such as myocardial infarction.1 Lp(a) is higher in females, rising by a mean of 8% post-menopause.2

So, are there any lipoprotein (a) links to CVD risk?

Lipoprotein(a): Links to CVD Risk

Lp(a) is composed of a cholesterol-laden LDL-like particle bound to a plasminogen-like glycoprotein, apolipoprotein(a).3

Lp(a) is considered an independent risk factor for heart disease. Recently, elevated levels of Lp(a) have been linked as a risk factor for stroke, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), and calcific aortic valve disease.4

The dual structure suggests that Lp(a) may be able to contribute to both atherosclerosis and thrombosis, and recent human genetic data support a role for Lp(a) in atherosclerotic stenosis in particular.5 This is no small impact, as atherosclerosis is attributed as the underlying cause of up to 50% of deaths in westernized society,6 while thromboembolic events are attributed to 1 in 4 deaths worldwide.7

Lp(a): Prevalence and Testing

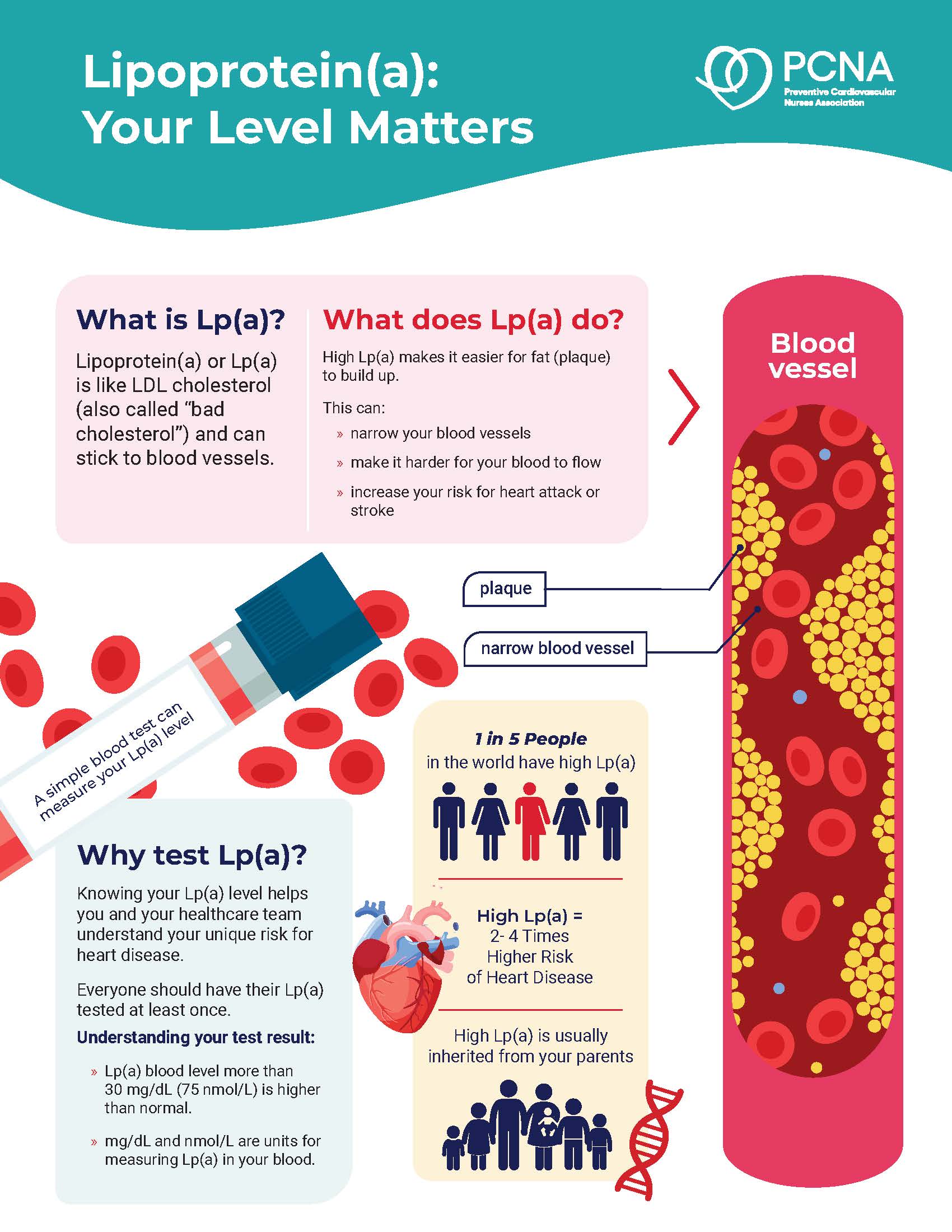

While a growing number of people may know their levels of LDL-C, and perhaps their triglycerides, knowledge about Lp(a) is lacking. An estimated 1 in 5 people worldwide have elevated Lp(a), yet most of them are unaware of this fact.8 This lack of information not only puts these individuals at greater risk for cardiovascular disease, but also puts family members who may also carry this genetically influenced at an increased risk.

Lp(a) is measured using a specific blood test that is not part of a standard lipid panel. It is important to note that individuals may have normal levels of LDL-C and simultaneously high levels of Lp(a). Elevated Lp(a) levels are those >75 nmol/L (>30 mg/dL); high levels are >125 nmol/L (> 50 mg/dL).

Measuring Lp(a) levels at least once in an individual’s lifetime helps to identify their unique risk for heart disease. Elevated Lp(a) can contribute to increased plaque accumulation, which may lead to narrowing of blood vessels, increased blood pressure, and an increased risk for heart attack and stroke.

While testing rates are increasing slightly, they still fall short in helping patients and health care professionals identify this important risk factor. The results of a recent study indicated that only 0.1% of adults in a cohort of 71 million individuals had ever been tested—yet the prevalence of elevated Lp(a) in the cohort was 21.4%.9

Testing recommendations include individuals with personal or family history of ASCVD that is not fully explained by major CVD risk factors. Identification of elevated Lp(a) is also an important genetic marker to share so that other family members can be effectively screened and treated.

Lp(a) Management and Treatment

For individuals with abnormal levels of Lp(a), it is important to address and control all other heart-related risk factors. Examples include cholesterol-lowering medications (e.g., statins, etc.) and aiming for LDL-C levels of <100 mg/dL for those with no history of CVD. For those with CVD, aim for levels <70 mg/dL, and a level of <55 mg/dL should be the goal for people with heart disease and other cardiac risk factors.

Heart-healthy lifestyle factors such as tobacco cessation, healthy eating, staying active, decreasing stress, attaining/maintaining a healthy weight, etc. are an important part of reducing overall risk for CVD.

Lipoprotein apheresis is currently the only therapy with FDA approval for treating Lp(a) and is only available if an individual has familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) and specific levels of LDL-C and other factors. (See this AHA statement for details.) While effective, the treatment is short-term and must be repeated regularly to keep Lp(a) levels low.

While there are currently no specific medications to lower Lp(a) levels, there are some promising therapies on the horizon. Stay tuned to pcna.net for more details as they become available.

References

- Brunelli C, Spallarosa P, Bertolini S et al. Lipoprotein(a) is increased in acute coronary syndromes (unstable angina pectoris and myocardial infarction) but it is not predictive of the severity of coronary lesions. Clin Cardiol.1995;18:526-529.

- Jenner JL, Ordovas L, Lamon-Fava S Et Al. Effects of age, sex and menopausal status on plasma lipoprotein(a) levels: The Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation.1993;87:1135-1141.

- Utermann G. Lipoprotein(a). In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Eds. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. McGraw-Hill, New York, 2753-2787.

- Borrelli MJ, Youssef A, Boffa MB, Koschinsky ML. New Frontiers in Lp(a)-Targeted Therapies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019;40(3):212-225. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2019.01.004

- Kamstrup P.R., Tybjærg-Hansen A., Nordestgaard B.G.; Genetic evidence that lipoprotein(a) associates with atherosclerotic stenosis rather than venous thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.2012;32:1732-1741.

- Pahwa R, Jialal I. Atherosclerosis. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507799/

- Wendelboe, A. M., Raskob, G. E. Global Burden of Thrombosis: Epidemiologic Aspects. AHA Circulation Research. 2016 Apr;118(3)

- Thanassoulis G. Screening for High Lipoprotein(a). Circulation. 2019;139(12):1493-1496. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.038989

- Bansai A, Cho L. Prevalence of Lipoprotein(a) Testing in a Contemporary Cohort. Circulation. 2025;151:9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.070361

Published on

December 15, 2025

PhD, MPH, RN, CDCES, FAHA, FPCNA, FAAN

Related Resources

Online Interactive Guides

Cholesterol: Journey to a Healthier Lifestyle Online Interactive Patient Guide

February 12, 2025