The data utilized for measuring quality in cardiovascular practice may be qualitative or quantitative. In this article, authors Brenda Owusu, Simone Chinnis, Serina Gbaba, and Diana Baptise ask the question: Are we treating people or numbers? Rethinking cardiovascular quality metrics through a nursing lens requires that quality measurement remain patient-centered and equitable, and helps achieve meaningful, sustainable health outcomes.

Cardiovascular Quality in Modern Practice

Cardiovascular care has increasingly relied on quality metrics to guide clinical decision-making, evaluate performance, and standardize evidence-based practice. Physiologic measures such as blood pressure targets, lipid thresholds, glycemic control, and readmission rates have contributed to measurable improvements in population-level outcomes. 1, 2 However, as cardiovascular disease (CVD) continues to disproportionately affect older adults, women, and individuals experiencing social disadvantage, questions remain about whether current quality metrics adequately capture the complexity of real-world patient care.3, 4, 5 While physiological markers remain essential indicators of cardiovascular risk and disease progression, they represent only one dimension of quality. Cardiovascular nurses are increasingly aware of a disconnect between the achievement of numeric targets in clinical settings and patients’ lived experiences of managing chronic disease in their daily lives.6, 7 This gap highlights the need to critically examine the definition, measurement, and operationalization of quality in cardiovascular care.

Beyond Traditional Metrics

In addition to the monitoring of traditional disease metrics, the National Committee for Quality Assurance, focusing on housing stability, food insecurity, and transportation, added Social Need Screening and Intervention in 2023, to their Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, a tool used by health plan insurers to continually assess and improve the quality of care that is provided to patients by healthcare facilities.8 Traditional cardiovascular quality metrics prioritize physiologic outcomes but often overlook social factors that directly influence the sustainability of those outcomes.7, 1 Nurses routinely assess barriers such as medication affordability, health literacy, caregiving burden, transportation limitations, and cultural beliefs, factors that profoundly influence adherence and long-term success but remain largely invisible in quality reporting systems that monitor treatment effectiveness.9 The American Heart Association (AHA) emphasizes prevention and risk reduction through guideline-directed care, but achieving these goals requires more than meeting physiologic numeric thresholds. Patients may meet numeric targets while experiencing unmet psychosocial needs, limited understanding of their disease, or unrealistic care plans within their social context.4,5 These gaps are particularly pronounced among older adults with multimorbidity, where aggressive treatment goals may conflict with functional status, patient preferences, or quality of life.3

When Metrics Drive Care

An overreliance on traditional quality metrics can unintentionally shift care away from individualized clinical judgment, eclipsing the importance of patient-centered care and preventing the cultivation of relationship-centered care.6 Cardiovascular nurses frequently encounter situations in which treatment intensification is pursued to meet benchmarks despite patient-reported side effects, cost concerns, or competing priorities. In these cases, patients may be mislabeled as “nonadherent,” when in reality, structural and social barriers are the primary drivers of suboptimal outcomes.5, 7 This dynamic contributes to moral distress among nurses, who are ethically obligated to balance beneficence, autonomy, and justice while navigating systems that reward numeric achievement over contextualized care. Without flexibility, traditional quality metrics risk reinforcing inequities rather than addressing them.

What Nurses See That Quality Metrics Miss

Cardiovascular nurses are well-positioned to recognize dimensions of cardiovascular quality that extend beyond numbers, as relationship-centered care is inherent to the profession. Beach and Inui (2006) presented the four precepts of relationship-centered care: 1) Personhood, 2) Affect and Emotion, 3) Reciprocal Influence, and 4) Moral Value. The nurse-patient relationship is grounded in personhood and respect for the uniqueness of each patient, which is evidenced through individualized nursing care plans.10 Nurses are positioned to learn about their patients’ emotional responses to care, eliciting emotional attunement and leading to the development of empathy and subsequently advocacy on the behalf of patients. Additionally, through bidirectional exchanges, nurses experience professional growth with every patient interaction. Furthermore, the nurse-patient relationship is fortified with each encounter eliciting a sense of genuine moral commitment through the growth of the patient-nurse relationship.

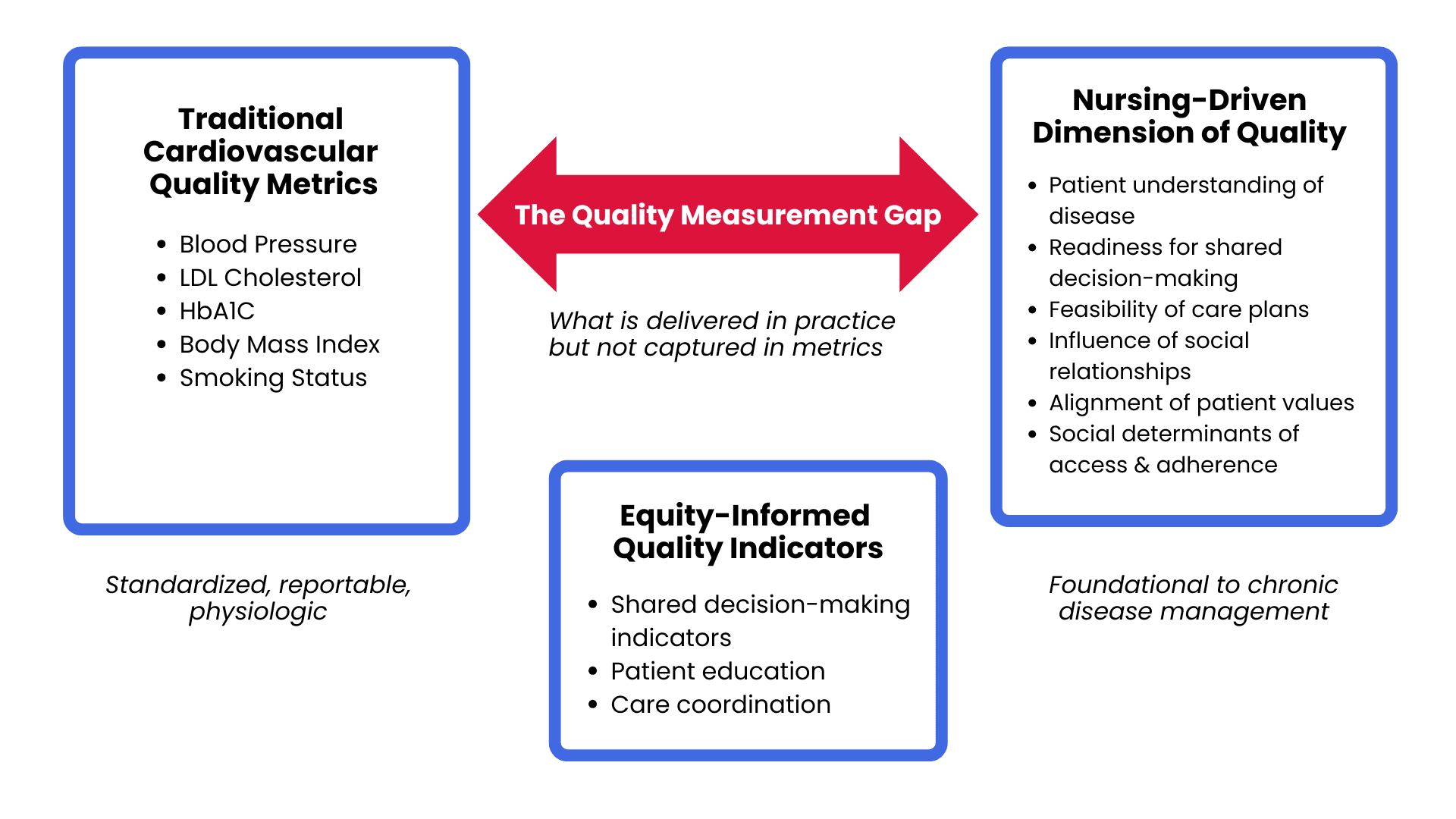

Through the application of relationship-centered care, nurses include patient understanding of disease processes, readiness to engage in shared decision-making, feasibility of care plans, impact of social relationships on disease management, and the alignment of treatment goals with patients’ values.10 Such elements transcend traditional metrics and are foundational to effective chronic disease management, albeit are rarely incorporated into formal quality frameworks. Reframing quality metrics through a nursing lens also brings health equity into focus. Metrics that ignore social determinants of health may unintentionally penalize populations with limited access to resources while obscuring systemic contributors to poor outcomes.12 The disconnect between traditional cardiovascular quality metrics and the broader, nursing-driven dimensions of care that shape patient outcomes. While conventional measures focus on standardized physiological indicators, nurses routinely address relationship-centered and equity-relevant factors, such as patient understanding, shared decision-making, feasibility of care plans, and social context, that are not consistently captured in formal quality frameworks (See Figure). The figure highlights the need for equity-informed indicators to better reflect the realities of cardiovascular nursing practice and support holistic chronic disease management. Such an omission creates a barrier to meeting the holistic needs of patients. Integrating equity-informed indicators, such as documentation of shared decision-making, patient education, and care coordination, would better reflect the realities of cardiovascular nursing practice.

Figure 1: The Quality Measurement Gap in Cardiovascular Care

Cardiovascular Quality Metrics: Implications for Practice

As cardiovascular care becomes increasingly driven by performance metrics, nurses play a critical role in ensuring that quality measurement remains patient-centered and equitable. Cardiovascular nurses are uniquely positioned to contextualize guideline-based targets by integrating social determinants of health, patient preferences, and functional status into care planning. Nursing practice must continue to emphasize shared decision-making, realistic goal setting, and advocacy when numeric targets conflict with patient needs or circumstances. Additionally, nurse leaders should actively participate in quality improvement and policy discussions to promote metrics that reflect both clinical outcomes and lived patient experiences. By doing so, cardiovascular nursing can help shift quality care from achieving numbers to achieving meaningful, sustainable health outcomes.

References

- Williams MS, Levine GN, Kalra D, et al. 2025 AHA/ACC Clinical Performance and Quality Measures for Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Performance Measures. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.0(0):e000140. doi: doi:10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000140.

- Singh K, Bawa VS, Venkateshmurthy NS, et al. Assessment of Studies of Quality Improvement Strategies to Enhance Outcomes in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113375. Epub 20210601. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13375. PubMed PMID: 34125220; PMCID: PMC8204210

- Kumar M, Orkaby A, Tighe C, et al. Life’s Essential 8: Optimizing Health in Older Adults. JACC Adv. 2023;2(7). Epub 20230823. doi: 10.1016/j.jacadv.2023.100560. PubMed PMID: 37664644; PMCID: PMC10470487.

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. JACC. 2019;74(10):e177-e232.

- Powell-Wiley TM, Baumer Y, Baah FO, et al. Social Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation Research. 2022;130(5):782-99. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319811.

- Nazir A, Nazir A, Afzaal U, et al. Advancements in Biomarkers for Early Detection and Risk Stratification of Cardiovascular Diseases-A Literature Review. Health Sci Rep. 2025;8(5):e70878. Epub 20250526. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.70878. PubMed PMID: 40432692; PMCID: PMC12106349.

- Metlock FE, Hinneh T, Benjasirisan C, et al. Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Hypertension Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Hypertension. 2024;81(8):1675-700. Epub 20240618. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.123.22571. PubMed PMID: 38887955; PMCID: PMC12166636.

- Yan AF, Chen Z, Wang Y, et al. Effectiveness of Social Needs Screening and Interventions in Clinical Settings on Utilization, Cost, and Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Health Equity. 2022;6(1):454-75. Epub 20220624. doi: 10.1089/heq.2022.0010. PubMed PMID: 35801145; PMCID: PMC9257553.

- Chan AHY, Cooper V, Lycett H, Horne R. Practical Barriers to Medication Adherence: What Do Current Self- or Observer-Reported Instruments Assess? Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:572. Epub 20200513. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00572. PubMed PMID: 32477110; PMCID: PMC7237632.

- Beach MC, Inui T. Relationship-centered care. A constructive reframing. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S3-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00302.x. PubMed PMID: 16405707; PMCID: PMC1484841.

- Qiu X. Nurse-led intervention in the management of patients with cardiovascular diseases: a brief literature review. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):6. Epub 20240102. doi: 10.1186/s12912-023-01422-6. PubMed PMID: 38163878; PMCID: PMC10759353.

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Johnson C, Thimm-Kaiser M, Benzekri A. Nurse-led approaches to address social determinants of health and advance health equity: A new framework and its implications. Nurs Outlook. 2023;71(6):101996. Epub 20230621. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2023.101996. PubMed PMID: 37349232.

Published on

February 3, 2026

DNP, APRN, ANP-BC, FNP-BC

DNP, MBA, AE-C, APRN, FNP-C

DNP, MBA, FNP-BC

DNP, RN, CNE, FPCNA, FAAN

Related Resources

Sorry, we couldn't find any resources.