What are the latest guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of heart failure (HF)? Guest Nancy Albert, PhD, CCNS, CHFN, CCRN, NE-BC, FAHA, discusses new HF classifications, diagnostic strategies including BNP measurement, the four pillars of HF medications, and overcoming barriers to ensure the most effective treatment for our patients.

Episode Resources

Welcome to Heart to Heart Nurses, brought to you by the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. PCNA’s mission is to promote nurses as leaders in cardiovascular disease prevention and management.

Geralyn Warfield (host): I’d like to welcome our audience today where we’re going to have a conversation with Dr. Nancy Albert about heart failure. Dr. Albert, could you please introduce yourself to our audience?

Nancy Albert (guest): Sure. I’m Nancy Albert. I am from Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio. I’m an Advanced Practice Nurse. I have a heart failure clinic I run on the main campus, and my main job is to be a nurse scientist. I am the Associate Chief Nursing Officer for Research and Innovation throughout our healthcare system in Cleveland and beyond.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Well, we have a great expert sitting across the table from us today, and we’re going to start off our conversation talking a little about heart failure prevention. Why don’t you tell us a little bit about what it’s going to take for us to help our [00:01:00] patients prevent heart failure in the first place?

Nancy Albert (guest): It’s really a great discussion we need to have about prevention because most people don’t think about it. They think about diagnosis, and once they’re diagnosed with heart failure, what are we going to do to prevent it from getting worse, to keep people alive, to keep them feeling like they’ve got a good quality of life?

But we do need to think about prevention because heart failure is a big problem in the United States. It’s one of the few cardiovascular diseases that’s growing in rate, not decreasing in rates as some other cardiovascular diseases are. Along with atrial fib, it’s the two, those are the two that are really increasing.

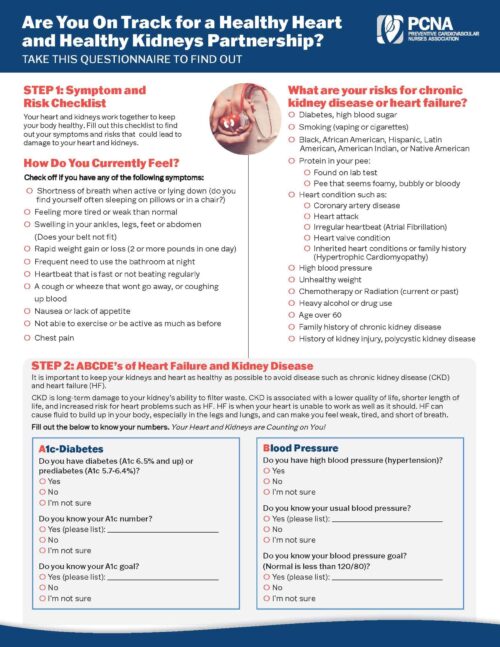

So, we need to think about prevention. And first of all, we need to think about a healthy lifestyle. So, we all know what that means. We may not all follow it, you know, is our weight in control? Are we physically active? Do we have a diet that would be more like a DASH diet, you know, fruits and vegetables, not the white carbs, you know, less red meat, [00:02:00] etc., so that we’re eating healthy? So, we need to think about all of those types of things.

Are we a smoker? Can we quit smoking? You know, what are we doing day in and day out to not just exercise, but to be active, you know, in terms of walking.

So, I think we, and then we also need to think about the preventive factors. Do we get flu shots every year? Do we see a healthcare provider regularly to just even be able to understand if something is emerging that maybe we didn’t sense?

One of the big problems of heart failure is it’s a condition of the elderly. And as we get older, we tend to make excuses for why we feel the way we do.

So, we know the two most frequent symptoms of heart failure are fatigue and shortness of breath.

But if we think about it, people will say things like, “Well, I’m tired because I was playing with the grandkids,” or, “I’m tired because my wife made me run around the mall yesterday with her.” Or, “I’m [00:03:00] tired because yesterday I was outside working in the yard.”

And so, we tend to think about excuses. Without really being tested to find out if maybe we’re not really like our twin brother or sister if we were standing next to them, and they didn’t have these symptoms.

So, recognition is really important. And then really trying to find out why, and what’s going on.

Geralyn Warfield (host): So, we all potentially have some risk factors for heart failure. And is there a way for us to identify patients who have multiple risk factors, to help us in that actual initial identification?

Nancy Albert (guest): Yeah, that’s a good question.

So, there are some research studies out there that looked at risk factors and did some multi-variable modeling and trying to figure out which risk factors were the most important and certainly anything in the cardiovascular disease family puts you at higher risk.

So, hypertension is in that realm as well. But coronary artery disease, and valve disease, people [00:04:00] who’ve had open heart surgery or have had stents, you know, anybody who’s had coronary artery disease, even if they never had a stent or open-heart surgery, maybe even just having chronic angina, that would be enough to put you at a higher risk.

We also know that vascular disease by itself could put you at higher risk. So, it could be a vascular disease that’s exhibited in the lower legs and it’s not in the heart. Certainly, having a stroke would put you at higher risk.

COPD also puts patients at higher risk. So, again, it may be the chicken or the egg. People are short of breath, and we assume it’s either asthma or COPD. We put patients on medications, they’re not getting better, and then we diagnose them with heart failure. Maybe they never really had the COPD or the asthma, but it does show up in that grouping of factors that put patients at higher risk for heart failure.

The last one is obesity. Although we can have obese patients that are very healthy, we all know that [00:05:00] being obese now puts people at higher risk for heart failure. We used to have what we called an obesity scenario where if you were obese, you were more likely to develop heart failure, but if you were obese, you lived longer with your heart failure than if you weren’t. And that has recently been debunked.

So, we just know in general, being obese is not a good scenario for our patients.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Can you talk just a little bit about biomarker testing?

Nancy Albert (guest): Yes. You know, there’s different biomarkers out there. The most important ones in heart failure are either high-sensitivity troponins, but even more important than that is BNP or N-Terminal-proBNP.

So, BNP is short for brain natriuretic peptide because it was first found in the brains of pigs. But in humans it’s produced in the ventricles. But it should really not be produced in our adults who are healthy.

So, a normal BNP [00:06:00] value is less than 35. We say it should be about half of your age.

So, for a typical 70-year-old patient with heart failure, it should be around 35. If you’re a hundred with heart failure, if you’re doing well, it should be less than 50. But when it gets above 125 picograms per milliliter, that’s a sign that it’s being produced in the ventricles because of wall stress. So, the heart’s working hard, something’s going on. It’s causing an increase in wall stress.

N-Terminal proBNP is not a hormone, it’s a byproduct when, pre-proBNP is cleaved out of the ventricle muscle into the bloodstream, you get the hormone BNP, and then you get this N-terminal-proBNP. And so, just like BNP, the rate, the amount in the bloodstream, should be very low.

When it gets above 125 picograms per milliliter, we say that’s above normal. We really start getting worried about it when it gets above 400, and if you’re elderly, it’s [00:07:00] if you’re over 75, maybe when it gets above 750 or 900. But the bottom line is when either BNP or N-terminal-proBNP is elevated, that’s a sign that the heart, the ventricular wall muscle is under stress, and it tells us something is going on that we really need to check out.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We’ve been talking with Dr. Nancy Albert about heart failure and indications that we might be otherwise missing, and even before that, how to prevent it. We’ll be right back.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We’re back with Dr. Nancy Albert discussing heart failure. And we understand that heart failure patients have a variety of complexities in terms of sometimes the comorbidities that they have, and other types of activities that they may no longer be able to do that they once were able to do with ease, and sometimes that’s the first indication, whether or not we all recognize it, that they do have heart failure.

I’m wondering if you could talk a little bit about the updated guidelines when it comes to the classifications of heart failure based on [00:08:00] ejection fraction.

Nancy Albert (guest): Yeah. So, when we think about ejection fraction, we used to have terms that we used all the time, heart failure and reduced ejection fraction—at one time, that was called systolic heart failure. So, we’ve updated it to reduced ejection fraction, and that’s an ejection fraction of 40% or less.

And then we had patients who had HFpEF, or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction—previously called diastolic heart failure. And for a while there, that was an EF of greater than 50%.

And then you had this funny little area, that from 41% to 49%, and we called that borderline HFpEF because early on when we started recognizing this abnormality, when we did research studies and authors, published them, we found out that the characteristics of patients in that borderline zone looked a lot more like patients with preserved ejection fraction than patients with reduced ejection fraction.

[00:09:00] However, we started putting, doing research trials and putting these patients in the HFpEF or the preserved ejection fraction category. And it turned out the drugs weren’t working so much in them, but they were working on patients with reduced ejection fraction who had what we call now mildly reduced ejection fraction.

So, the new terms today are:

HFrEF: reduced ejection fraction, EF of less than or equal to 40%

Mildly reduced ejection fraction, which is that 41 to 49%

And then heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, which is 50% or higher.

And we have to remember that for all of us people walking around without heart failure, our normal ejection fraction is 60% or higher.

So, these are people who have HFpEF that may look like they’re having a normal heart function, but they really have heart failure because they’re having symptoms, either current symptoms or previous symptoms [00:10:00] of heart failure.

Geralyn Warfield (host): I appreciate you going through those new classifications so that we can better understand what kinds of mechanisms we can put into place to actually help treat these patients.

And so now that we have these new classifications, could you talk a little bit about the new recommendations for treatment?

Nancy Albert (guest): Yes. So, when we think about taking care of our patients with heart failure, heart failure and reduced ejection fraction is the most complex, because we have the most number of drugs available to us.

And we need to remember that our patients are not living on an island with just heart failure. They have comorbidities. You already mentioned that. They have diabetes, they have atrial fib, they have gout, they have COPD, you know, goes on and on.

And so, they’re on other drugs in addition to what we’re trying to put them on. And it gets very difficult for patients to juggle all of their medications.

But we now have 4 pillars of heart failure medications. and this does not [00:11:00] include diuretics. So, loop diuretics would be a fifth drug if our patient is having symptoms of fluid overload or congestion.

But the four core drugs are a drug in the renin angiotensin system family; and the drug of choice right now is an ARNI. ARNI stands for angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor. We only have one drug available. It’s sacubitril and valsartan. So, until more drugs come available, that is now the leading drug. And it’s actually, recommended above taking an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, also known as an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker.

So, the guidelines have now said if a patient can tolerate an ARNI, that that should be our drug of choice. And then if they cannot tolerate ARNI, the next drug of choice is an ACE inhibitor.

If they cannot tolerate an ACE inhibitor, then the next drug in that group is an ARB, or an angiotensin [00:12:00] receptor blocker.

And each level has higher efficacy.

So, when we think about an ACE inhibitor or an ARB, we used to think of them as kind of equivalent, but we know they’re not. You have a better chance of survival if you’re on an ACE inhibitor than if you’re on an angiotensin receptor blocker. But if you’re on an ARNI, which is that an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, you have the biggest bang in terms of improved quality of life and decreased hospitalization and improved survival.

So that’s on the HFrEF side.

In addition, there are drugs that are available when patients have worsening heart failure, and their problem is heart failure in reduced ejection fraction. For years we’ve had hydralazine and nitrates for our African American patients, or patients who couldn’t tolerate a renin angiotensin system agent.

We also have vericiguat that could be added on. It’s a nitric oxide, [00:13:00] synthesis agent, a stimulator agent. So, we’ve got these other drugs that can help us out to have effects that are maybe similar to the renin angiotensin system, but work in different pathways.

So that’s all the one class.

Of the other three pillars, the next pillar is a beta blocker, and we only have three beta blockers that are approved for use in heart failure, and we need to make sure we choose one of those three. So that would either be carvedilol, metoprolol succinate (the long-acting version, not the short-acting version), or bisoprolol.

And then, a mineral corticoid receptor antagonist is our third core drug, or third pillar. It used to be called an aldosterone receptor antagonist, so ARA. Now we’re used to using the term MRA because it’s really targeting the mineral corticoid receptor, not just being used as a potassium sparing diuretic.

And then our last drug category [00:14:00] is a new one. It’s a sodium glucose cotransporter two inhibitor, or an SGLT2 inhibitor. And it’s really because of previous research in our diabetes patients that we even found out about this drug being a good drug.

Back in the early, I think it was, 2000s, there was a class of drugs that came out for diabetes that actually caused heart failure and caused worsening heart failure among patients who were taking it for their diabetes. So, our Food and Drug Administration decided that any new diabetic agent that came on the market needed to be tested for cardiovascular disease.

So, during the testing, the goal was just to make sure it didn’t cause harm. Who would’ve ever thought that it would be beneficial? And it would actually become a pillar of our heart failure therapies for our patients with HFrEF?

So those are the four pillars, and then again, the diuretic can be added on when needed.

Geralyn Warfield (host): [00:15:00] So, the treatment of our patients with heart failure is a very complex web of looking at the types of medications that are available, using them at the right amounts and at the right times. And I’m wondering if you could just discuss for us a little bit about up-titration and how that might affect how we are treating our patients.

Nancy Albert (guest): Yeah. Thanks for raising that. It’s a really important topic.

So, we have this problem in the United States where we have provider inertia. And what I mean by that is we know the right drugs to use in heart failure, especially if you’re part of the heart failure community. and we know the right doses patients should be on, and they’re the doses that were used in randomized controlled trials that showed the right evidence of improved outcomes.

But when we see in reality, when we do retrospective chart reviews and even multicenter studies, is that patients may be placed on some of the right drugs, but not all of the right drugs. And then even [00:16:00] when they’re on the right drug, they’re not at a dose that effectively keeps them out of trouble in the long run. They’re not at a target dose for them.

And so, we need to really do a better job of getting our patients on the right drugs, those core four, and then also up titrating the drugs to what we call target doses or the highest tolerated dose by the patient.

And if it’s not the dose that was used in research, we need to make sure we record that so that the next provider who comes along can understand why somebody is not on the right dose of the right drug. Because it could have been a problem that was modifiable.

For example:

I’ve got the flu. I’m not tolerating anything.

My blood pressure’s low because I’m not eating and drinking as I normally should.

I’m dizzy all day.

I’m lying around.

Maybe this isn’t the time to uptitrate my drug, but if somebody did do that and the patient got became more dizzy, we won’t, you know, we don’t want to take it off of the patient.

But we don’t want to just stay at [00:17:00] that low dose forever. Now they’re healthy two months later. We need to reconsider getting them on the right dose and making those changes.

Part of the problem is the inertia of providers, as I mentioned. The other part of the problem is the systems and processes we have in place within our hospitals and our healthcare centers, including our ambulatory centers.

And also patients are part of that as well. So, of course, we have a problem if a patient is scheduled to come in for up-titration and fails to show. But I think even more important than that is what are we doing within our hospitals and healthcare systems to facilitate and encourage patients to do the right thing?

Are they aware that we’re giving drugs that are almost like a stepping stone, and you can’t get them on everything at one time. You have to do it slowly over time and up-titrate slowly. If patients understood that, I think they would be more likely to come in and follow the [00:18:00] rules. But they don’t really understand the rules, and if they believe they’re feeling fine, and we lead them to believe they’re stable, then why would they think they need to come in?

So, we need to learn how to use the right terminology with our patients. We shouldn’t be using the word “stable.” There is no such thing as a stable heart failure patient. We know that today. We could say your heart failure is active, or your heart failure is persistent.

So, if we use the right terminology to help our patients understand what’s going on, and then we teach them about how to take care of themselves, then maybe they’d be more likely to follow along, and be on the right drugs at the right doses.

Geralyn Warfield (host): You have given us an astoundingly wonderful overview of the new guidelines and the new terminology that we need to use and the new pillars of heart failure medications that we have.

Is there anything else that you would like to add that we haven’t discussed already?

Nancy Albert (guest): Yeah. I’ll just mention that you know, we talked about the medications for heart failure in reduced ejection fraction. [00:19:00] The guidelines have also now, because of heart failure in mildly reduced ejection fraction, and of course heart failure and preserved ejection fraction, they’ve come up with new algorithms for medications for those two groups as well.

And you know, you may be interested to know that diuretics as needed is at the top of the list. So, if somebody’s symptomatic, that they would be on a diuretic.

But both mildly reduced, and HFpEF now have an SGLT2 inhibitor as the next target drug, even above, a renin angiotensin system agent or a mineral corticoid receptor antagonist agent. And so, I think down the road we’ll be seeing more SGLT2 inhibitors in use.

And who knows where we’re heading. We know that there are some other drugs in the pipeline that may be coming out down the road.

And I didn’t mention one other drug, and this is a really interesting drug. It’s again, for HFrEF, but for patients who have an elevated heart rate greater than 70 beats per minute, [00:20:00] And they’re on a beta blocker, a maximally tolerated dose of beta blocker, there’s a drug that got FDA-approved back in 2015, so we’re talking it’s seven years old now. And I very rarely see it used even in patients that meet the criteria for it. It’s called ivabradine. And it’s used much more heavily in Europe than it is in the United States.

But again, we need to remember that we’ve got these extra drugs we could add on when patients have specific scenarios. Not to mention CRT and ICD, which are devices that can be added on when patients need it.

And so, we need to look at our whole tool chest of resources and consider what is available for our patients when we’re thinking about that big picture.

Geralyn Warfield (host): For our listeners who have questions about anything that you have discussed, do you have any resources that you would suggest?

Nancy Albert (guest): Yes. I think that the American Heart Association has really good references online, as does the Heart Failure Society of America. [00:21:00]

If it’s a nurse who’s listening, there’s the American Association of Heart Failure Nurses. They also have a wonderful website full of resources for people.

And I’m not sure if PCNA has information online as well. So, I think there are resources available for people that have patients and they want their patients to go to a source or a site. Both the AAHFN and the HFSA, the Heart Failure Society, have portals for patients with patient materials and also patient-lead or -initiated educational resources.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Thank you so very much for those excellent resources. It has been wonderful to spend time with you today, learning more about heart failure and current management strategies. I am your host, Geralyn Warfield, and we will see you next time.

Thank you for listening to Heart to Heart Nurses. We invite you to visit pcna.net for clinical resources, continuing education, and much more.

Topics

- Heart Failure

Published on

December 19, 2023

Listen on:

PhD, CCNS, CCRN, NE-BC

Related Resources