Applying guidelines-directed therapies for antiplatelets and antithrombotics requires balancing the risks of cardiovascular events and the risk of bleeding. Guest Erin Michos, MD, MHS, FACC, FAHA, FASE, FASCP, describes the use of shared decision-making with patients who are at higher risk for thrombotic events and discusses pharmacotherapies recommended for use with particular patient groups.

Episode Resources

Welcome to Heart to Heart Nurses, brought to you by the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. PCNA’s mission is to promote nurses as leaders in cardiovascular disease prevention and management.

Geralyn Warfield (host): I’d like to welcome our audience today to our conversation with Dr. Erin Michos, and I’d like to have her introduce herself to you.

Erin Michos (guest): Great. So, as you heard, I’m Dr. Erin Michos. I am a cardiologist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and I focus on preventive cardiology and women’s health.

I’m the Associate Director of Preventive Cardiology, and I’m the Director of Women’s Cardiovascular Health Research.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Well, we have a lot to discuss today. We’re going to be actually talking first about guidelines and aspirin. So, obviously, we’ve seen some changes in cardiovascular care and in antiplatelet and antithrombotic therapies in recent years. And I’m wondering if you could talk to us [00:01:00] a little bit about how guidelines have changed from endorsing aspirin in primary prevention, and what kind of patients might we see in our clinical settings that might be candidates for using aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease?

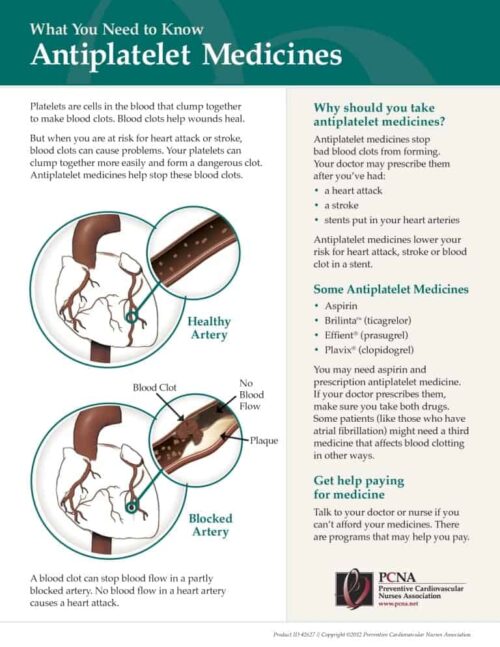

Erin Michos (guest): Great. So, you know, in this talk I gave at the [2023 Annual] PCNA meeting, I covered both anti-platelets for primary prevention, which means individuals that haven’t had an event yet—we’re trying to prevent that first event—and secondary prevention: so, individuals who’ve either had a heart attack or a stroke or a stent or revascularization or a known coronary disease. And we’re trying to prevent a second event.

Now for aspirin, it’s still strongly indicated in secondary prevention. And we can talk a little bit more about some of the other anti-platelets we use in secondary prevention.

But in primary prevention, there really has been this rise and fall, this evolution. So, it started with the older trials in the 1970s and 1980s in primary prevention, demonstrating a benefit of [00:02:00] aspirin. But things were different back then. We weren’t really using statin therapy in the 80s, 90s, for primary prevention. And there was much more smoking, and blood pressure was less well controlled.

And since that time, so based on those earlier trials, some of the earlier American Heart Association guidelines had given a strong recommendation, a Class 1 recommendation, for using aspirin in primary prevention for patients that were estimated to be at elevated risk, estimated to have more than a 10% risk of a coronary event in the next 10 years.

But since that time, there’s been more trials. And really three pivotal trials that came out in 2018: the. ARRIVE trial, the ASCEND trial, and the ESPRIT trial. And, really, the trials ultimately showed that there was really more harm than benefit. In the ARRIVE and the ESPIRIT trial, there was no reduction in major cardiovascular events, but there was increased risk in bleeding.

The ASCEND [00:03:00] trial, which enrolled persons with diabetes, there was a slight benefit in reducing vascular events, but this was really overshadowed by significant increased risk of a bleeding.

And so, since that, there’s been a change in guidelines. I was a co-author in the 2019 AHA/ACC Primary Prevention Guidelines. And we gave the recommendation for aspirin in primary prevention a 2b recommendation. So, this is a downgrade from that 1A.

So, what does 2b mean? It means, really, for most healthy adults, you know, no, we wouldn’t use aspirin in primary prevention. But the aspirin could be used selectively, may be considered in individuals who were estimated by elevated risk of a vascular event, but are at low risk for bleeding, who are ages 40 to 70.

So, who might those people be? Well, it may be someone who has significant subclinical disease, like a coronary calcium score above 100. Or they have elevations in their lipids that are [00:04:00] not well controlled, or elevated lipoprotein(a). Maybe they’re current smokers, maybe they have strong family history. So, you can use that selectively in some people, as long as they’re not at increased risk of bleeding.

And then we gave a Class 3 recommendation, which means don’t use, in adults over the age of 70. That’s because the EPIRIT trial, which enrolled adults over the age 70, you know, it showed no benefit in vascular events, and there was more bleeding and even more death–the mortality was higher in the aspirin arm. So, we don’t recommend it above age 70, or for anybody at increased risk for bleeding.

And then, in 2022, last year, the U.S. Preventative Service Task Force came out with a statement. They also don’t give a really endorsement for aspirin. They gave it a Class C recommendation, which means, really, it’s an individual decision between a patient and their doctor, but you know, may be considered. Again, these really weak recommendations, may be considered in adults age 40 to 59, who are at elevated 10-year risk above [00:05:00] 10% for a cardiovascular event. Who are not increased risk for bleeding.

So, this really gets into shared decision making, and what, who those patients might be. But for most healthy patients, we’ve really moved away from using aspirin for primary prevention because the risk benefit ratio is pretty narrow, because vascular events are lower in primary prevention, but the bleeding risk is comparable.

But again, sometimes patients heard this news, and they stopped aspirin when they really were a secondary prevention patient. So, this does not apply to patients who’ve had a prior heart attack, or a stent, or bypass surgery. Aspirin is still recommended in the secondary prevention population.

Geralyn Warfield (host): So, having that shared decision-making conversation with your patient for primary prevention in some cases may be appropriate. But what I’m hearing loud and clear is aspirin is no longer—thanks to the guidelines updates—to be used for primary prevention in most of our patients, but for secondary prevention should be continued then.

Erin Michos (guest): Yes.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Fabulous. So, let’s switch directions just slightly. [00:06:00] For patients who undergo PCI for acute coronary syndrome, or have stable ischemic heart disease, can you tell us a little bit about dual antiplatelet therapy, or DAPT? And, in particular, as I think about the clinicians who are listening to this, how do they decide the length of time to continue DAPT versus returning to single anti-platelet therapy or SAPT, and what factors might they keep in mind as they’re making these decisions?

Erin Michos (guest): Yeah, so this is, these are challenging.

So, the CURE trial, which came out in 2002, enrolled patients with acute coronary syndrome. And back then in 2002, actually only a third got a stent. So, this was, this is acute coronary syndrome with or without a stent. And compared clopidogrel plus aspirin, what we call dual antiplatelet therapy, versus aspirin alone, and showed significant benefit reduction in cardiovascular events.

And since then, it’s become a Class 1 recommendation—that in patients with an acute [00:07:00] coronary syndrome, whether they have a stent or not, if they were an ACS patient, so they’ve had either a non-STEMI or a STEMI (either one), that we try to do 12 months of DAPT.

Now, then there was a series of studies comparing some of the more potent anti-platelet agents with clopidogrel.

So, the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial compared prasugrel compared to clopidogrel. And showed that the more potent antiplatelet agent did reduce vascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome that were getting a stent. So, these are all patients with ACS in this trial that were getting a stent, but it came at a cost of a significant increased risk of bleeding.

And there was also increased hemorrhagic stroke in patients that have had a stroke or TIA in the past. So, you don’t want to use prasugrel for patients that have had a prior stroke. But it did show superiority over clopidogrel, and the other group of patients with ACS undergoing a stent.

And then there was the PLATO trial, also patients with acute coronary syndrome [00:08:00]—not necessarily undergoing a stent or not—showing that ticagrelor was superior to clopidogrel in reducing vascular events but, again, there can be an increased risk of bleeding. But because of that superiority, the guidelines did give a 2a indication: that if you’re going to use DAPT, which if you’re using an aspirin plus a second anti-platelet (a P2Y12), the preference would be to use either prasugrel or ticagrelor over clopidogrel because of the superiority of, of reducing vascular events.

Now, as I mentioned, the standard after ACS was 12 months. What happens after 12 months? Well, there’s been some studies that’ve looked at extended DAPT, meaning longer than 12 months. And they did show that if you treat with dual antiplatelet therapy longer, you can prevent vascular events.

But it comes at that cost of increased risk of bleeding. So, you use longer therapy and you reduce events, but cause [00:09:00] more bleeding. And so that’s this balance.

There’s a number of calculators, like the DAPT calculator, and the PARIS calculator [PARIS thrombotic risk score] that, that have… also the PRECISE-DAPT, you know, is another one, where you enter in patient characteristics and try to figure out that risk benefit ratio of which patients are more likely to have a vascular event, versus which patients are more likely to bleed, to kind of decide whether you might extend beyond 12 months.

Then there’s the question about what if you have a really high-risk patient with acute coronary syndrome, you know, that, who we’re recommending 12 months, but they’re at really high risk for bleeding. Can you deescalate, can you stop a therapy earlier? So, there was a series of five trials that looked at de-escalation.

So, one of them was the TWILIGHT trial. This was actually patients who’ve had a stent who were at high risk for bleeding. And looked at, they got three months of a DAPT. They got the dual anti-platelet for three months, with aspirin and ticagrelor, and then they randomized them [00:10:00] to after three months, just going to ticagrelor alone versus staying on DAPT.

So, when they dropped an anti-platelet, you know, they’re dropping the aspirin. So, they’re comparing ticagrelor alone, with aspirin plus ticagrelor, and showed that that strategy significantly reduced bleeding. As you can imagine, just one agent versus two reduced bleeding, but didn’t seem to come at a cost of worsening the vascular events; didn’t increase the risk of MI or stent thrombosis.

So, after that, in the more recent 2021 American Heart Association guidelines about chronic coronary disease, they do give that option that for patients who’ve had acute coronary syndrome, if they can’t make it to 12 months, that you could potentially de-escalate at one to three months. And if you’re going to de-escalate, to drop the aspirin and to stay on the P2Y12. So that’s a 2a option.

And then they have the other option, which is 2b—a bit weaker—that in some select cases you may treat longer than 12 months on the converse side.

So, it’s really a challenge and you have to think about [00:11:00] patient characteristics. Also characteristics about their anatomy: Did they get that stent for a heart attack that puts them into a higher risk category, or did they get that stent for like stable angina? You know, did, was there the size of the stent, the complexity of the anatomy, was there bifurcating lesions? All this kind of goes into these decisions about whether we really want to treat with more potent therapy for longer. Because that has benefit, but it comes at this trade off of higher risk of bleeding.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We’re going to take a quick break and we will be right back.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We’re back with Dr. Erin Michos, discussing anti-platelet therapies and some differences and similarities that we need to keep in mind so that we can have the best patient outcomes.

It sounds like, Dr. Michos, that we have a lot of considerations when it comes to using these pharmacotherapies, and I’m wondering if you could talk a little bit more about some of the factors to keep in mind, maybe about methods of action, or mechanisms of action, for the P2Y12 inhibitors. Could you do that for us?

Erin Michos (guest): Yeah. So, you know, the first one in the [00:12:00] series that I started with is talking about clopidogrel.

So, clopidogrel is a pro-drug, which means it needs to be activated to be the active drug. And unfortunately, there is a lot of genetic variability in how people metabolize this drug. So, there can be a substantial amount of clopidogrel resistance, which means that the amount of platelet inhibition by this drug can vary from person to person.

And there are some genetic tests that you can do to see if someone’s going to be a clopidogrel responder or non-responder, but that’s not always widely done in clinical practice. And so, as I mentioned, the guidelines—particularly for high-risk patients with acute coronary syndrome—have favored the more potent antiplatelet therapy, the prasugrel and ticagrelor over clopidogrel for that reason.

So, both clopidogrel and prasugrel are thienopyridines, and they are irreversible inhibitors of the P2Y12 receptor. So, the P2Y12 is a receptor on the platelet. That’s [00:13:00] normally where ADP binds to that for platelet aggregation. So, by inhibiting that receptor, it kind of prevents the platelets from getting activated and aggregating.

And so, those drugs inhibit for the life cycle of the platelet. So, the platelet has a life of about seven days, and so the bone marrow is always making new platelets, but they have a longer action; they hang around longer.

So that has considerations if your patient needs to go for surgery. Generally, you know, you’d want to hold the clopidogrel for five to seven days before surgery, or prasugrel for seven to 10 days, prasugrel being more potent and also being irreversible inhibitor. So that’s some factors to consider.

Now, ticagrelor…so, just on the dosing: clopidogrel’s dose: 75 milligrams a day; prasugrel is dosed 10 milligrams a day. And as I mentioned earlier, you don’t want to use prasugrel in persons who have had history of stroke or TIA. And prasugrel was only indicated in people who were going to be [00:14:00] undergoing stent placements—so it’s not used in ACS when if someone’s not getting a stent.

And you also want to maybe dose reduce prasugrel if they have a low body weight under 60 kilograms. And we generally try to avoid it in older adults who are over the age of 75 because of that hemorrhagic stroke risk. But if you’re going to use it an older adult, maybe you also dose reduce to five milligrams instead of the standard 10 milligrams.

So then, getting to ticagrelor. Ticagrelor is actually not a thienopyridines. It inhibits P2Y12 by different mechanism, and it’s actually a reversible inhibitor, meaning that it can dissociate from that receptor, so that it doesn’t last as long. Which has advantages if someone’s potentially going to be heading off for surgery, like bypass surgery, it could be stopped, you know, after three to five days. You know, the bleeding risk is lower, so has a much shorter, sort of, duration of action.

In acute [00:15:00] coronary syndrome, we use the 90 milligram twice a day dosing. There was also a trial called PEGASUS that looked at more the stable population, so people who were more than a year out from a heart attack or more. And if you’re going to use ticagrelor as part of that extended DAPT—that long term beyond 12 months—then you would dose reduce to 60 milligrams twice a day plus aspirin.

So those are the major differences. Yeah, so, in terms of patients that may need elective procedures, if they have had a recent stent, particularly with acute coronary syndrome, we really don’t want to stop the antiplatelet therapy if, you know, if we can’t, unless this is absolutely an emergency.

So, we really try to delay any elective surgery until we can get to a patient at least 12 months of DAP therapy, if they got it for acute coronary syndrome, or at least six months if they got a stent for stable ischemic heart disease. Because the stents need time to re-endothelialize [00:16:00] over. And so, the earlier, the more recent the stent is, there are more risks for stent thrombosis, acute stent thrombosis, or even sub-acute stent thrombosis.

So, any patient taking an anti-platelet agent or an anticoagulant, they really need to discuss with their cardiologists about when they can come off of it, and for the timing and the safety of it.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Could you tell us just a little bit more about the COMPASS study and how that affects our treatment of patients with CAD and PAD?

Erin Michos (guest): Yeah, so the COMPASS trial was another secondary prevention trial, 27,000 individuals who had coronary disease or peripheral arterial disease, they had vascular disease.

And it looked at a strategy of using aspirin alone, you know, for secondary prevention, versus using aspirin and a low dose anticoagulant. So, rivaroxaban, 2.5 milligrams, twice a day—again, this is a much lower dose than you might be familiar with, [00:17:00] with using rivaroxaban when we use it to treat AFib or treat venous thromboembolism. So, this is a low dose. They also had a third arm, which looked at rivaroxaban alone.

So, what we saw was that if you use this, you know, more potent strategy of using an anti-platelet (aspirin) with a low-dose anticoagulant—so, kind of getting at it two ways by inhibiting the platelets and also the thrombotic system—significantly reduced vascular events compared to aspirin alone.

But it came out of course at this cost of increased risk of bleeding that we can never get away, that when we use more intensive therapy, we can prevent more vascular events, but it increases the risk of bleeding.

But one thing, in looking at the subgroup, there was over 7,000 patients in COMPASS that had peripheral arterial disease. And so, not only did the strategy of aspirin plus low dose rivaroxaban reduce major adverse cardiovascular events, there was also a significant reduction of more than [00:18:00] 40% in reduction in major adverse limb events like revascularization or amputation in these patients with PAD.

So, when we’re thinking about, you know, which patients we might want to do this strategy, to use aspirin plus a low dose anticoagulant, rivaroxaban, you know, I sort of [start] thinking about my patients who are at the very highest risk: the polyvascular disease patients that have vascular disease in more than one territory in their coronaries and peripheral arterial disease. And I sometimes think about that strategy, that more intensive strategy, in those types of patients.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Great information. I have a specialized population I’d like us to discuss, and that’s individuals that have AFib. And for those patients that have PCI with stent who also have AFib, what’s the current approach to managing that antiplatelet therapy with, also, their antithrombotic therapy?

Erin Michos (guest): Yeah, so this gets to be really challenging. So, you know, we need the anti-platelet—typically, [00:19:00] historically, it was always DAPT (aspirin plus a P2Y12)—for those that have had a recent stent, and then they needed the anticoagulant for their AFib.

And so, historically, we used to do something called triple therapy. So, they would have the anticoagulant, either a DOAC (a direct oral anticoagulant) or warfarin, and they would have their two antiplatelet drugs. And of course, the bleeding risk was really high.

And then there was a series of studies, four different trials, that looked at dual therapy as opposed to triple therapy.

And when I mean dual therapy, I’m not talking about DAPT. I’m talking about one antiplatelet agent and one anticoagulant in this population. And these trials showed that using dual therapy, as opposed to triple therapy, you know, substantially reduces bleeding risk, as you might imagine. And didn’t seem to significantly increase the risk of stent thrombosis or of an MI.

So, the current [00:20:00] recommendations from the 2021 AHA guidelines about treating chronic coronary disease. Instead, if somebody gets a stent and they have AFib, to try to do triple therapy, you know, with DAPT plus and anticoagulant, for one to four weeks. So, you still want at least a little bit of triple therapy, but after one to four weeks, to drop one of the antiplatelet agents—and they recommend dropping the aspirin.

So, when they to, when you are using dual therapy to use a P2Y12, like prasugrel or ticagrelor, with the anticoagulant. And then for the anticoagulant, they really recommend whenever possible to really use the DOACs (the direct oral anticoagulants) over warfarin, because the direct oral anticoagulants have much lower bleeding risk.

And so that’s really become the standard of care after a very brief period of triple therapy to really move to dual therapy in these patients.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Erin, you have given us so much to think about when it comes to treating these patients with these different pharmacotherapies. Is [00:21:00] there anything else that you would like to add that I’ve neglected to ask?

Erin Michos (guest): No, it’s just that this can be a challenging conundrum in clinical practice. You know, we know that the more intense we do with anti-platelet therapy, and adding anticoagulants, we can reduce some residual risk for vascular events. But this comes at an increased cost of bleeding. So, it’s really striking a balance and trying to figure out which patients are at greater risk for having a thrombotic event versus at greater risk for a bleeding event.

And this is part of shared decision making, and it has to be individualized for each patient based on their risk profile.

Geralyn Warfield (host Thank you so very much for being here today. This is your host, Geralyn Warfield, and we will see you next time.

Thank you for listening to Heart to Heart Nurses. We invite you to visit pcna.net for clinical resources, continuing education, and much more.

Topics

- Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS)

- Pharmacology

Published on

August 29, 2023

Listen on:

MD, MHS, FACC, FAHA, FASE, FASPC

Related Resources