Nancy Albert, APN, and Rimsky Denis, MD, discuss current studies in ASCVD risk reduction for patients with–or at risk for–Type 2 Diabetes. They also describe strategies for shared decision-making in clinical practice for managing cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Earn 0.6 CE contact hours from listening to the podcast episode and completing the course components.

Supported by an independent medical education grant from Novo Nordisk.

Welcome to Heart to Heart Nurses, brought to you by the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. PCNA’s mission is to promote nurses as leaders in cardiovascular disease prevention and management.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Welcome to the second of a three-episode miniseries focused on type 2 diabetes, GLP-1 RAs, and cardiovascular disease.

This particular episode is available for CE contact hours. Please make sure to follow the link in the episode show notes to complete your posttest and your evaluation, and then access your CE certificate.

We also encourage you to listen to the other two episodes in this particular mini-series to get even more information than our conversation today.

My guests today are Rimsky Dennis and Nancy Albert. Rimsky, could you introduce yourself, please?

Rimsky Denis (guest): Certainly. My name is Rimsky Dennis. I am an Interventional and [00:01:00] Structural Cardiologist based out of Miami, Florida.

I’m also a member of the Association of Black Cardiologists.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Thank you. Nancy, could you please share a bit about yourself?

Nancy Albert (guest): Sure. I’m the Associate Chief Nursing Officer for Research and Innovation in the Nursing Institute throughout the Cleveland Clinic Health System. I’m stationed in Cleveland, Ohio, and I’m also a Clinical Nurse Specialist in the Kauffman Center for Heart Failure Treatment and Recovery on the main campus and see patients with heart failure in the outpatient setting.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Wonderful. Well, I am sure our listening audience can tell that there’s a great deal of expertise on our podcast episode today. So, let’s go ahead and get started. First of all, could we please do a quick review of the links between ASCVD and type 2 diabetes? Obviously, there’s similar risks for both, and could you please briefly describe those?

Rimsky Denis (guest): The risks are very similar between ASCVD and type 2 diabetes. The [00:02:00] risks include obesity. sedentary lifestyle, lack of exercise, poorly controlled hypertension, smoking, elevated cholesterol, and a diet high in carbohydrates.

Nancy Albert (guest): I’d like to add that, you know, when we think about atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes, we know that 2/3 of Americans with type 2 diabetes are going to develop atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in their lifetime. So, that’s 2/3, that’s the majority of patients with type 2 diabetes. So, it’s really important to control some of the risk factors that Dr. Dennis just talked about.

Some are harder to control than others for some patients, and patients really need to understand their condition. So, for example, hypertension is silent and so, patients may not even realize they have hypertension unless they take an active measure to check their blood pressure or see their internal medicine or other family practitioner on a regular [00:03:00] basis.

Obviously, smoking and obesity, and some of the other ones, are a little bit more obvious. But there are, another one is sedentary lifestyle that can also lead to cardiovascular disease and get our patients into trouble who have type two diabetes. So, if they’re already obese with hypertension and they’re sedentary, that could really, that mixture, that threesome could really get our patients into trouble.

So, we need to treat the comorbid conditions and treat the diabetes at the same time. It’s not just a matter of treating diabetes.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Thank you both so much. I’d like us to dive just a little bit deeper into what the current research indicates about ASCVD reduction for these patients that have type 2 diabetes.

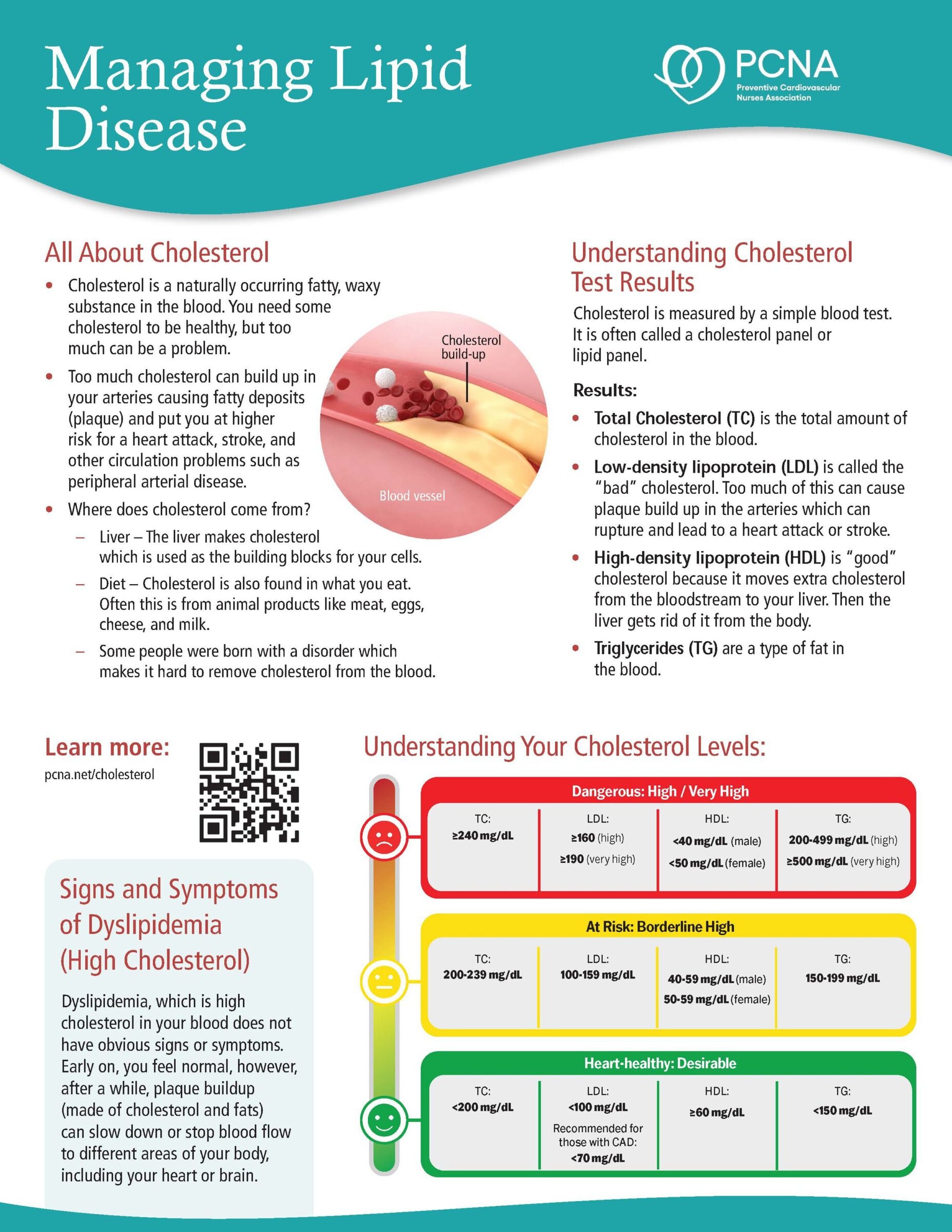

Nancy Albert (guest): So, I’ll go ahead and get started on that one. So, you know, we know that when patients have type 2 diabetes, and they have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, we know that high-intensity versus moderate-intensity statins can lower LDL cholesterol, the [00:04:00] low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and the very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

And these patients are really at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, as we just mentioned. And because of that, we create different limits to what we expect the LDL level to be.

So, for example, most of our lab work in our hospitals say that if your low-density lipoprotein is below 100, you’re in good shape. But at least in my center, if somebody is at low risk for cardiovascular disease, we really want them to still get down to about 70. Because research that was done years ago, with devices inside the coronary arteries, started to show that if you get your LDL below 70, you could actually see reversal of plaque buildup.

And so, you could take a vessel that already has some plaque in it, and most of our vessels do once we get to a certain age, we could see reversal. And now we know we should even [00:05:00] go lower.

So, in our patients that are at high risk, and again, the diabetic patients are at high risk for atherosclerotic disease, we really want to see their LDL level to be 40 mg/dL.

So, you know, patients will say to me, “But my values are in the normal limit. I don’t need to worry.”

And we’re like, “No, you do need to worry because we know you’re at higher risk for getting into trouble down the road.”

Geralyn Warfield (host): I’m wondering if either one of you could answer for our audience, how you can demonstrate to our patients the importance of this whole array of medications that we’re asking them to take, because it’s often a large volume, and how do you stress the importance of these as well as everything else that we’re requesting that they take on a regular basis?

Nancy Albert (guest): Ah, the age-old question of polypharmacy. So, you know, we’ve got patients who have diabetes and, as Dr. Dennis mentioned, they may also have other medical conditions. They may have comorbid conditions. They may be on lots of [00:06:00] medications. Some of our hypertensive patients are on three drugs just for the hypertension alone.

So, you know, patients need to really figure out how to take the medications in a way that meet the criteria of the medication. So, for some drugs, we want patients to take it in the morning. For example, some of our diabetic agents, because we want them to take them before they eat. But for other drugs, we can take them at noon or at dinnertime, or even at bedtime, especially if they’re once a day agents.

And we need to figure out how patients can take the drugs in a way that allows them to remember their medications so they’re adherent. And also take them in a way that does not cause dizziness, lightheadedness, can lead to dehydration, which could lead to hypovolemia and get them into trouble.

So again, we need to look at that big picture and figure out how to do it best. And it really is individualized. It’s not a one-stop-fits-all for patients. So, getting to [00:07:00] understand how our patients live their lives can really help us out.

For example, for hypertension, usually patients are on a diuretic and that diuretic may make them have to need the bathroom more often, right? So, you know, if somebody’s driving to work, they may not want to take it until after they get to work where a bathroom is nearby. They don’t want to be stopping at gas stations along the way. So, that’s just one example.

We need to kind of understand what’s going on with our patients so that we could give them the best information about how to manage their lifestyle and remember to take their medications that are so important to them.

Rimsky Denis (guest): I agree with Dr. Albert wholeheartedly. Many of the patients that we see have many disease processes and have comorbid conditions. So, getting patients to comply with the barrage of medications that they’re often subjected to can sometimes be challenging.

One of the things that I’ve realized in my practice that has been helpful [00:08:00] in efforts to achieve medication adherence with patients who have multiple medications is really trying to get to the crux of why the medications are necessary—without going through a medical school rigorous course on the different ways in which the medications work, you know.

I try to, you know, educate them on the basic aspects of the medications, right? I explain to them why the ACE inhibitor is important when they have diabetes, particularly with regard to protecting their kidneys. I explain why certain medical medications for diabetes are important with regard to decreasing the risk of atherosclerotic disease around the arteries that supply blood to their heart, right?

We go over a list of different things and a list of different benefits that each medication has. And I think, you know, questions arise or oftentimes questions arise from the patients. And that gets [00:09:00] us to a better understanding overall as to some of the barriers that the patients may have.

And it also allows us to answer, you know, some of the questions, and some of the concerns that they may have with regard to certain medications. Like, for example, if patients are taking diuretics, they may not be aware that it’s one particular medication that they might be not be aware of why that medication is causing them to use the restroom more frequently.

But I think, you know, when we have those conversations and we flesh out some of the concerns that patients have, the likelihood that they’ll adhere to the regimen, is higher.

In addition to that, it also gives us an opportunity to address some of the social determinants of health barriers that may exist unbeknownst to us.

Nancy Albert (guest): You know, he’s making some really good comments here and, you know, we need to remember that some of the newer drugs our patients are on are more expensive. And they’re not all oral anymore.

So, a GLP-1 RA, for example, is [00:10:00] subcutaneous, that’s usually how we give it, and it’s once a week, So, they don’t have to take it every day, but they have to learn how to give themselves a subcutaneous medication and because of the expense we have to explain to patients why are we adding it on. We have to share that value proposition with them.

So, we can explain to them that you may still be on metformin or another agent for your diabetes, but this drug will help you to have better control without hypoglycemia—so, your glucose level will go down to a dangerously low level.

And at the same time, it’s giving you the cardiovascular protection that’s So, important for you. We’re decreasing your risk of stroke, we’re decreasing your risk of cardiovascular mortality, and we’re helping to protect the kidneys a little bit.

And so, again, it’s that bigger picture that sometimes the patients need. But we need to keep it simple, we need to keep it easy, because patients, if it’s too complex, patients [00:11:00] really won’t understand what’s going on, and they’ll kind of get lost in the middle of everything.

So, when we think about the mechanism of action in our GLP-1RA, so, again, these are our glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists, we need to think about what’s really going on behind the scenes. We know that patients who take these agents are going to have enhanced glucose dependent insulin secretion. So, more insulin is going to be coming out of the pancreas and that’s going to help them with their control of their glucose.

They’re going to have slowed gastric emptying. They’re going to have a reduction in postprandial glucagon and food intake. So, these patients are often less hungry. A couple of my patients that are on these agents tell me they get full fast, and they don’t feel as hungry in between meals. So, they definitely are eating less than normal, but again, it’s less likely to cause hypoglycemia. [00:12:00] And because of that, it’s got a safety profile that can really be beneficial to our patients with type 2 diabetes, and especially if they have obesity.

We know that that different drugs in this class can cause weight loss for our patients. And so, patients need to know about that so that they’re not worried if that happens.

And really, the rate of weight loss really depends on the drug of choice. One drug will pretty much cause about a 12-pound weight loss. Another drug can cause only as little as a four-pound weight loss. So, it really depends on the agents. And the providers need to explain that to patients so they’re not shocked when they’re losing weight, if indeed they weren’t planning on losing weight.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We’ve been talking with Nancy Albert and Rimsky Dennis about the relationship between type 2 diabetes, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and cardiovascular disease. We are going to take a quick break [00:13:00] and we will be right back.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Welcome back to our audience as we speak with Nancy Albert and Rimsky Dennis about how to understand and reduce cardiovascular and cardiometabolic risks, particularly in our patients that have type 2 diabetes. And what are some of the benefits in terms of utilizing team-based care in managing these two diseases of cardiovascular disease and diabetes?

Nancy Albert (guest): Well, for sure it takes a village. You know, these patients have more than one condition. Usually, they have more than just cardiovascular disease and diabetes. They may have other medical conditions. And everybody comes to us with different lifestyle, background, different habits, different economic status, socioeconomic status.

They may live in communities where they’ve got food deserts, or they don’t have transportation to come in and see healthcare providers. And so, we need to remember that the team concept of taking care of these patients is really important. They need to hear [00:14:00] messages from more than one person. Everybody on the team needs to understand what’s really going on with them in terms of how best to guide them in care.

For example, I may have one patient where I tell them to get one of those cute little pill organizers so that they can do a good job of care. But we have other patients that a pill organizer is not going to cut it because they’re not sure what pills to put in which sections of the organizer. So, we actually have our pharmacy create these cute little packets.

They’re sealed and, you know, one’s for morning, one’s for lunch, one’s for dinner, one’s for bedtime. And so, the patient’s got all four or five pills that they need to take at that moment in time sitting in that packet. And all they need to do is, you know, see what time of the day it is, open the packet and take their medications.

So even if they’re not sure what is what, we can be a little more believing that they’re taking the right medications at the right times. So, that’s one thing to think about. [00:15:00]

Rimsky Denis (guest): Absolutely. There’s been a paradigm shift in medicine, I would say, over the last 10 to 15 years, where the team-based approach, the multidisciplinary approach, has become the standard of care.

Now in medicine, or medical schools, students are being taught how to manage patients with nurses, with nurse practitioners, with physical therapists, and with a host of different other ancillary and other, you know, specialists to ultimately achieve optimal health for their patient. This is something that wasn’t taught when I was in medical school. But, again, there’s a paradigm shift where we’re moving more towards getting everyone involved with regard to a team-based approach to achieve the best care possible.

So, the benefits of a team-based approach with regard to diabetes management, and ASCVD management is basically having a centered, [00:16:00] patient-focused approach, where the patient receives all the necessary resources in the simplest, most streamlined way possible while addressing issues pertaining to social determinants of health barriers that the patient may have.

Again, this means that we all work together with nutritionists, endocrinologists, pharmacists, podiatrists, optometrists, ophthalmologists, and other specialists that patients may require to manage their diabetes.

And again, I’m going to stress this, but I really believe that this ensures that patients receive the highest care possible in efforts to achieve the best healthcare outcomes.

Nancy Albert (guest): I agree completely about that.

And, you know, we need to remember that there are so many new devices and programs that are available on the market today that weren’t even available a few years ago.

We’ve got artificial intelligence. We’ve got little patches that can go on patients to tell us what’s going on with hemodynamics and [00:17:00] even fluid in the chest. We have, obviously, telemonitoring and telemanagement programs today. We have so many new, so much new availability of services that could really help our patients do a better job of taking care of themselves.

And if we think about the big picture, a typical physician who’s billing for care has maybe 10 or 15 minutes with the patient, typically in an office visit. But most patients really need a lot more time than that. And so, you know, the provider of record can really explain to patients what needs to happen, but then it works really well to have a team behind that person who can explain the medications, explain why they need to go to cardiac rehab, explain what the signs and symptoms are of cardiovascular risk in case we’re worried about an acute MI or some other risk factor based on lab [00:18:00] results that we’re seeing, explain what to expect if their urine changes color, what that means for them.

All of those little nuggets of information take time, they take effort. They take one-on-one intensity, usually, or family intensity with the patient. And it can’t be done by one person because our providers are busy trying to see the next person. And since COVID-19, at least in most of the places that I talk to, hospitals and ambulatory care centers, they’re busier than ever.

So, we have a lot more patients coming into the healthcare system that need to be diagnosed and treated, and we really need to use that team model to really help make sure all of our patients are getting the optimal care they deserve.

Geralyn Warfield (host): I really appreciate the complexity of what it’s like to be a healthcare professional in today’s time, in terms of all the other influences that [00:19:00] you have on your time, and also how many influences there are on the patient.

And so, I’m wondering, there is no typical patient, but if you think about a patient in your practice, what does team-based care look like specifically for that patient in your particular practice?

Nancy Albert (guest): So, I’ll start with mine and then we’ll have Dr. Dennis add on here.

So, in my patient practice, my patients typically have heart failure. It may be reduced ejection fraction, mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. It’s very common for me to see the patient also have diabetes, type 2 diabetes is more prevalent than type 1 diabetes. And the background that maybe led to the heart failure is either hypertension, cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease. So again, vascular disease is a really prominent problem.

And so, we’re seeing younger patients now because of the obesity epidemic going on, and many of our patients are [00:20:00] obese. I would say, on average, the typical BMI, body mass index is well over 30, and for some patients, even higher than that.

And so, again, we need to think about what’s really going on in totality and be able to explain to patients all the different aspects of care that are required to not just treat, in my case, the heart failure, but to think about how that intersects with the diabetes, how that intersects with obesity, how that intersects with cardiovascular disease or hypertension, if that’s part of their underlying problems.

Are they smoking? Are they drinking? You know, so, there’s a lot to discuss for those patients. So, patients are coming in with multiple conditions, multiple medical conditions, and it leads us to spend a lot more time in the mode of shared decision-making, where we explain. What we want patients to be doing, how we want them to do it, but we give them options [00:21:00] and they have to buy into the option that’s going to work best for them.

And it may be that that option changes over time. I’ve had many patients who say, “You know, instead of you treating my hypertension with another drug, I want to try diet first.” I’ve learned not to let them try diet for too long of a period of time because 99% of the time it doesn’t work and so, I do have to put patients on medications, but if they want to try that, I want to offer it to them that way.

They’ll be more comfortable when I say, “OK, it’s time to add a drug because of the fact that it didn’t really do what we wanted it to do. So, that gives them the sense of why we’re taking the next steps.

So, I think it’s really important with the obesity epidemic going on and all of the medical comorbidities that we really take that time to listen to them, to get the team involved, and to really find out what works best for the individual patients.

Rimsky Denis (guest): Yeah, I would say that the average patient who comes to see me in the clinic, [00:22:00] as an interventional and structural cardiologist, the average patient has the top four, which I call them the top four, disease processes, which include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diabetes.

These are conditions that are managed by myself and a group of individuals that we have on our team, including nurse practitioners, nutritionists, podiatrists, ophthalmologists that we often refer to, and also a nephrologist, in addition to individuals who provide health education on a host of different levels.

That being said, the problem is complex. The issues are complex and having a team only ensures that as many issues are addressed, or the most issues are addressed, you know, in one inpatient visit or an outpatient visit. So, again, you know, [00:23:00] I think a team-based approach is necessary to be able to tackle these issues because the complexity of these issues are extensive.

Nancy Albert (guest): The other thing that works really great about a team-based approach is that some patients are going to have side effects from the medications they’re on.

For example, we know that the GLP-1 RAs can lead to pancreatitis, again they can lead to hypoglycemia, they can lead to hypovolemia, because patients are losing some water. And if they are dehydrated because they’re not drinking enough, they may actually become dizzy and lightheaded. And so, having a team approach gives patients more personnel that they can talk to about what’s going on.

We find that a lot of patients don’t want to bother a physician. I hear that all the time. “I don’t want to bother my doctor.” And so, having a team approach allows patients to call somebody up on the team who can give them the right advice for the right problem and also allow them to have that comfort of [00:24:00] “OK, I’m doing the right thing. I’m acting appropriately. I’m not just stopping medications inappropriately and getting into trouble down the road.”

Geralyn Warfield (host): I’m so grateful to you all for sharing such impressive information that we all can use in clinical practice to help these patients that have multiple comorbidities and so many things that they’re dealing with on a regular basis. And having that messaging, that information, come from a variety of sources and it’s all kind of similar information I think helps a patient understand better, helps a patient really recognize the why of, you know, they’re being asked, or encourage to do particular actions or take particular medications.

I don’t know if there’s anything else that we haven’t yet covered that you’d like to share, but now’s a great time to do that. And even if it’s a resource that you would like to lead other healthcare professionals towards, whatever might be on your mind.

So, Nancy, would you like to start?

Nancy Albert (guest): Well, I would just say that the American Heart Association, the American College of [00:25:00] Cardiology, and depending on other conditions the patient has, whether it’s, if it’s preventive, PCNA, the Preventative Cardiovascular Nursing Association. If the patient has heart failure, the Heart Failure Society of America.

But a lot of these national organizations have websites, or part of their website includes patient education and patient materials. And that could be really important for patients. For example, someone taking a GLP-1 RA may have diarrhea. They may have a little nausea. Diarrhea, it turns out, is a pretty common side effect. It only affects maybe less than 10% of patients, but that’s a pretty common side effect for patients taking it.

So, knowing that this is a normal side effect, they don’t have to stop taking the drug, they just have to worry about getting enough fluid on board so that they’re not getting behind on fluids is a really important message.

So, I would encourage patients, or encourage healthcare providers, to send their patients to some of these national websites that [00:26:00] really have very good information on cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

And I didn’t even mention the American Diabetes Association, but they also have a plethora of information that would be very important to share with patients.

Rimsky Denis (guest): I echo the sentiment shared by Nancy 100%. In addition, I wanted to put a plug in for education. I believe that we must continue to make efforts in the area of educating our patients and community members on the importance of chronic disease prevention and management.

As an interventional cardiologist and structural cardiologist, I was trained on placing stents and placing new valves and things of that nature. And although I love doing that, I think prevention is the key, particularly as it pertains to ASCVD risk.

One study that I recently read, estimated that an excess of 1.6 million lives, particularly in minority communities, were [00:27:00] lost over a 12-year span due to factors associated with ASCVD risk, which represented more than 80 million years of potential life lost. That’s a major, it’s a huge number, and this is a major issue that’s affecting our communities.

And we must continue to work hard to prevent further losses.

Nancy Albert (guest): Well said.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Most definitely. I would certainly like to thank our guests, Nancy Albert and Rimsky Dennis, for all the great nuggets of information that they have shared today.

I want to also remind our audience that this episode is available for CE contact hours. You’ll want to check through to the links in the show notes and that will lead you to complete an evaluation and a posttest and then you’ll be able to access your CE certificate.

We also would encourage you to listen to the other two episodes in this mini-series for more information.

Thank you to Novo Nordisk for funding support of this podcast [00:28:00] episode.

This is your host, Geralyn Warfield, and we will see you next time.

Thank you for listening to Heart to Heart Nurses. We invite you to visit pcna.net for clinical resources, continuing education, and much more.

Topics

- Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD)

- Diabetes

Published on

October 31, 2023

Listen on:

PhD, CCNS, CCRN, NE-BC

MD

Related Resources