Join National Kidney Foundation team members to take a deeper dive into the impact of elevated blood glucose and hypertension on kidney function. Dr. Andrew Bzowyckyj PharmD, BCPS, CDCES, and Elizabeth Montgomery to learn tips on identification, screening, and management of cardiorenal conditions.

This episode was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Episode Resources

- Article: Chronic Kidney Disease Testing Among At-Risk Adults in the U.S. Remains Low: Real-World Evidence From a National Laboratory Database

- PREVENT Online Calculator

- Article: Estimated Prevalence and Testing for Albuminuria in US Adults at Risk for Chronic Kidney Disease

- National Kidney Foundation: Chronic Kidney Disease Change Package 2023

- National Kidney Foundation: Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease

- Article: A Retrospective Multi-site Examination of Chronic Kidney Disease Using Longitudinal Laboratory Results and Metadata to Identify Clinical and Financial Risk

- National Kidney Foundation: Tool to assess undiagnosed CKD at your institution (PDF)

Welcome to Heart to Heart Nurses. Brought to you by the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. PCNA’s Mission is to promote nurses as leaders in cardiovascular disease prevention and management.

Geralyn Warfield (host): I would like to welcome our audience today to an episode where we’re going to take a deep dive into the impact of hypertension and diabetes on kidney function. I have two great individuals at the table today, Dr. Andrew Bzowyckyj and Elizabeth Montgomery. They are representing the National Kidney Foundation, and I’m going to let them introduce themselves to you. Elizabeth, could you start us off?

Elizabeth Montgomery (guest): Sure. Thank you for having me today. My name is Elizabeth Montgomery. I am the National Vice President of Learning Strategies and Population Health Programs at the NKF. I lead the teams that create all of the educational content that is produced by the National Kidney Foundation, and I lead the [00:01:00] population health team that is focused on closing the significant gaps in care that exist for people living with kidney disease in primary care and even specialty settings.

Thank you ever so much, Dr. Bzowyckyj, could you please introduce yourself to our audience?

Andrew Bzowyckyj (guest): Absolutely. Thank you for having me today. My name is Andrew Bzowyckyj. I’m a senior scientific director and learning consultant with the National Kidney Foundation. In this role I work a lot with the educational and programming content that we offer to patients and professionals.

My background is in clinical pharmacy and I’m also a diabetes care and education specialist, so I’m really happy to be here to talk with you all about that today. And then my practice experience has been in academic, pharmacy, primary care and in the endocrinology settings.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Well, thank you again for both of you to be here today for our discussion, and let’s go ahead and start our discussion speaking about hypertension and diabetes, and in particular, the impact of each of those on kidney function.

Andrew, do you think maybe you could start us [00:02:00] off providing an overview of the impact of elevated glucose?

Andrew Bzowyckyj (guest): Yeah, I can try. I’m sure your audience is well aware, obviously diabetes is omnipresent in clinical practice, hypertension as well. And when you add the two together, it certainly magnifies each other. So, when we think about overall patient care and I think back to my diabetes educator days, you’ve got the trifecta, the hypertension, the diabetes, and high cholesterol. Not everyone has all three, but when you put the three together, they just really magnify each other. So when you’ve got elevated glucose, we think of, you know, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, kind of rumbling through those blood vessels, tearing up the blood vessel linings, that creates kind of more problems. In hypertension then you’ve got the vasculature, you know, stressed out, trying to kind of compensate and manage all of these things. And then when you add in the cholesterol, the atherosclerosis, it tends to kind of block the blood vessels a bit. And so you have trouble, you know, pushing that blood through. And the three really kind of magnify each other.

A lot of times it meets up, you [00:03:00] know, in the heart, but then for sure in the kidneys, as the kidneys are trying to regulate and understand what’s happening. You know, how can I help, how can I compensate? Sometimes leading to overcompensation. And so the system’s essentially out of whack. And it really leads to many long-term consequences, again, as your audience very well knows.

Geralyn Warfield (host): And so let’s talk a little bit about the risk stratification process. What does that look like in terms of, as a clinician, as someone who’s treating people with, , all of these comorbid conditions, what does that look like?

Andrew Bzowyckyj (guest): Yeah, this is something that’s a lot harder to do in practice but I see it as the right thing to do. So, as we see our guidelines are steadily evolving to think about as we learn more about each of these individual disease states separately, but then also how you kind of overlap them together. We are really trying to individualize that care for that patient. Historically I think of the tenure of the ASCVD risk calculator and [00:04:00] even the Framingham cohort before that. Actually that one did not include diabetes, so remove that one. But the newer one, when we added diabetes into the equation, it was a yes no check box.

You know, when I was in diabetes practice, we had folks, you know, who had just been diagnosed. We had folks who had diabetes for a very long time. Both had the same A1C or different A1Cs. It’s not a yes or no kind of box, but that was just the best information we, at the time, that we had. And so now we’re learning a lot more about, you know, a person with a A1C of 12 is in a different situation than a person with A1C of, you know, six or seven. Two people with the same A1C, there’s been a lot of new data with continuous glucose monitors, we’re able to get more nuanced information. So two people with the same A1C, you know, if someone’s rumbling up and down from extreme highs to extreme lows, that’s a very different picture than someone with the exact same, you know, average A1C and yet much more kind of steadily managed.

So we’re learning much more about glucose specifically and how to use that to kind of individualize that risk. And then you [00:05:00] can take that into blood pressure and we’re learning more about, you know, even the, the uACR, which we’ll talk about later, albuminuria levels. All of those pieces help really customize to that patient so that they’re not just in an algorithm. You can kind of try to customize that care for those individual patients.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We really appreciate the fact that it’s not a one size fits all checklist that is used in this clinical setting in terms of diagnostics, in terms of care, in terms of management of individuals, with all these things going on.

But I suspect that one of the things that is a significant barrier to getting people to their healthcare goals are the gaps that we see. And Elizabeth, I’m hoping you could talk a little bit about the whole variety of gaps that you might see when it comes to this.

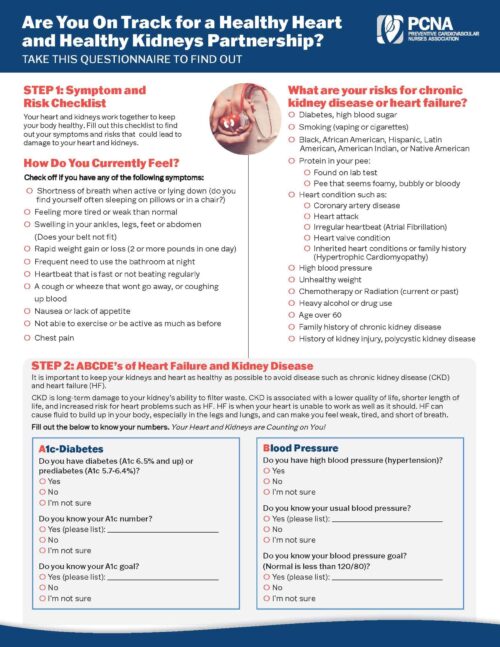

Elizabeth Montgomery (guest): Certainly, again, I appreciate the question. So the latest data that we have on the cardio kidney metabolic world is that the majority of people with [00:06:00] kidney disease, or are at risk for kidney disease, are not even receiving basic testing. So only about 45% of people with diabetes are being tested annually, and only about 10% of people with hypertension are being tested annually.

So if you look at that from a holistic perspective, that’s only about 20% of those at risk being tested on an annual basis. Why does that matter? Realistically, you know, Andrew mentioned, oh, sorry, Dr. Bzowyckyj mentioned earlier that chronic kidney disease significantly elevates risk for cardiovascular events and mortality. In primary care clinicians, rightfully, have the perspective of linking chronic kidney disease and end stage, which is 10 years [00:07:00] away. So there’s a degree of inertia that arises around that thinking that totally negates the increased risk for cardiovascular events. And so this discussion, the first discussion of the gaps that exist is around that testing that urine albumin creatinine ratio and in eGFR or serum creatinine with eGFR are very powerful predictors of cardiovascular events and mortality in their own right that often are not being reflected, or there’s no action being taken around them in the absence of a diagnosis or recognition of the laboratory findings that are in the eGFR.

So the first gap is that gap of closing the testing, and then that follows with the gap of assigning a diagnosis and appropriate risk stratification on the basis of the information in the [00:08:00] electronic health record. So that’s gap number one. Then you have the basic gaps in medical management of chronic kidney disease.

There was data that was published in a large retrospective study in 2019 that illustrated that the majority of people with chronic kidney disease, with a diagnosis, were not receiving guideline concordant care. Most people were not on an ACE or an ARB. Most people did not have, were not on a statin, and they did not have their A1C or blood pressure within recommended limits. So there’s lots of opportunity to close those gaps, particularly with the advent of the new interventions that have been demonstrated to slow or CKD progression and reduce cardiovascular risk by as much as 30% in a relatively short period of time. So those are the gaps that we’re looking to close in the [00:09:00] work that we are doing.

Geralyn Warfield (host): There’s another aspect to this individualized care that Andrew, I’m hoping you could address, and that has to do with the words that we’re using, the phraseology, the terminology, and the importance of having that be a little bit different in terms of what we may have used in the past compared to what we need to be using now.

Andrew Bzowyckyj (guest): Yeah, there’s been a lot of significant movement in this area, more so recently, but it’s been an ongoing thread I know in just how we interact with patients and how we describe patient situations. And how we describe working through the patient care scenarios, right? So, we think about, why don’t you just take your medicines or why don’t you just do this? Or Why don’t you just do that? And it’s funny when we think about just all of the things we do as clinicians on a day-to-day basis. How many of us eat, you know, the correct foods at the correct times. You know, how many of us, brush and floss our [00:10:00] teeth twice a day? Do you brush more frequently when you go to the dentist? Those types of things. And so really, in the diabetes space specifically, there’s been a lot of work to try to moderate some of the terminology, the language that we’re using. And I’ll admit it’s hard myself as a clinician thinking through these words.

But one of the big ones that I hear very frequently is the control. You know, who’s uncontrolled and who’s controlled. And obviously that has very negative connotations, but even just thinking about… this person is trying to do manually what their pancreas does automatically without even thinking. It regulates glucose down to the second. And so this idea that somehow you can control that, or anything else in our lives, the fact that you can have this control, is awfully presumptive. And so similar terms, you know, in terms of adherence or compliance. And even adherence was meant to be the better term for compliance. But even [00:11:00] that, you’re still following someone’s orders. And so you know what is the adherence? And so I like the recommendation to describe the behavior.

You take your medicines regularly, or you remember 80%, or you’re not able to take your medicines due to cost or scheduling or whatever it may be. And when you identify the issue, that helps to really work towards the solution. So instead of blaming and shaming, you know, it helps to identify the barrier and how do we help work through that.

There’s a lot from the diabetes space, but then we’re seeing this move into other areas as well. I know much of this also comes from the disabilities science and thinking through how we use terminology, because if you start off, you know, even if you don’t mean it, I think a lot of it, I do truly believe a lot of it is unintentional, but when you start off blaming and shaming, whether it be intentional or unintentional, conversation really doesn’t go very farfrom there. And these are some very difficult issues to work through. So trying to team up with patients I think is helpful. [00:12:00] And let’s get started on the right feet as clinician.

Elizabeth Montgomery (guest): So, Geralyn, if I could just add to what Dr. Bzowyckyj just stated, I think it’s really important that we recognize in the language that we use, that cardio, kidney and metabolic are all related, and that it is not one system that is breaking down. It’s all of them that are breaking down. And so when we talk about the work that we’re doing from a prevention perspective we generally don’t talk about end stage renal disease. We stay focused on the cardiovascular implications of this relationship so that we don’t get into that head space of separating them in the language that we [00:13:00] use. The second thing that I, I would add to, to what Dr. Bzowyckyj just outlined is what people tend to forget or may not fully appreciate is the role of health-related social needs in this conversation of the patients that we’re working with.

In my mind, there are no non-compliant patients. There are individuals who are struggling with those health-related social needs. That are standing in the way of them being able to actually demonstrate the self-management behaviors we would like to see. And that is particularly true with chronic kidney disease.

When you consider the populations that are at disproportionate risk, these are individuals who are struggling financially, may be experiencing food insecurity, may have low levels of [00:14:00] academic attainment, and may live in communities that have been historically marginalized. And, where there’s not been a lot of investment in a variety of different types of infrastructure.

All of those things conspire to increase risk and increase the speed of progression so we need to stay away, as Andrew mentioned, from that blaming and shaming language, because the reality of it is many people do not have the resources that those of us on this call might have that would allow us to engage in perfect self-management on a daily basis.

Geralyn Warfield (host): I am so impressed by not just your ability thus far in our conversation to talk about the interconnectedness of the science of the systems, but the interconnectedness of the people. With patients at the center of a patient-centered care plan, but also the need for individuals who are within any stage of clinical health to [00:15:00] really address the person as a whole. And Andrew, I know you had some more thoughts about that, that you were going to share with our audience. I’m hoping you could do that for us next, please.

Andrew Bzowyckyj (guest): So as we look at individualizing care, obviously it should be very simple and I realize that that’s not. So we have these guidelines and we have all these competing conditions that Elizabeth mentioned that are all part of the same body, right? We’re helping people live the healthiest lives that they can. And so as I mentioned earlier the guidelines and the tools that we have in clinical practice are really moving us towards trying to provide this individualization. Snd the big thing that’s always been omnipresent in cardiovascular care is risk and we’re seeing that trickle into to other areas as well.

One thing that I think will be a useful tool moving forward, and it’s relatively new, but for example, the American Heart Association has the new PREVENT calculator which really takes that, I mentioned earlier the pooled cohort equation which we’ve been [00:16:00] using for cardiovascular care for at least the last 10 years, and adds some additional layers of complexity. So the new calculator, you know looking at it includes BMI. And we know BMI has its flaws but as a whole, on a population-based level, you know, it can provide some additional levels of risk calculation there. eGFR, as Elizabeth mentioned, eGFR is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, that’s now part of that. So you can factor in somebody’s kidney stage into what their overall cardiovascular risk is for the next 10 years.

Then there’s also some optional factors that are included. So a uACR, the albuminuria that we’ve mentioned earlier. Again, another independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease that is now part of it. So if you have that information, you know, it’s helpful to put in there to even further risk stratify. And if you don’t have that information, chances are you should probably obtain that information by getting that testing done to have, again, that extra level. A couple other [00:17:00] things, as we’ve already mentioned, the zip code, which is a surrogate marker for social determinants of health.

So, we all know the zip code where you live really decides many, many factors of your healthcare and your overall kind of life that you’re leading. And so that can be added again as an option to help further risk stratify. What I see the benefit in these things, so people may wonder, why do we need this? Why are we using this? It really helps, I think, these are pieces that can help zone in. And so when you’re talking with the patient about what this number means, right? So you enter all this data, it spits out a number and helping to contextualize that information for a patient. And then what can you move, you know, you can potentially move the needle on BMI, you can potentially move the needle on uACR.

Maybe you can’t move the needle on, you know, eGFR, it’s more or less fixed where it is. You know, maybe you get some movement one way or the other. But those are some things that specifically can work on. I didn’t mention A1C earlier. But that’s another [00:18:00] one that’s an option in the new equation.

And so, you know, hey, look, if we lower your A1C, and I’ve played this game with patients before. I call it a game in jest, but if you were to stop smoking, let’s just flip this toggle over. Now, here’s the score. I flip my screen around to show the patient, if I flip this over to a no, let’s say you’re not smoking, it doesn’t happen overnight, but over five years of being quit, or 10 years,wherever the… I forget where the statistic lands.

Now, this could be your risk, you know? So if you don’t have that event in the near future, this could be your risk moving forward. Or if we lowered your blood pressure to this point. And showing them how these actionable changes can help decrease their overall risk for, for cardiovascular events.

One of the elements that’s in the new AHA PREVENT calculator is the eGFR. And so we know that is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. And as that goes down the cardiovascular risk does go up. And so we know that there’s not many [00:19:00] things that we can do to reverse, you know, the eGFR to bring it up, but there are many things, both long established and also newer treatments, newer interventions that we have that can help prevent that progression, prevent that decline, and so those are also things that we should certainly be focusing on.

Elizabeth Montgomery (guest): So the National Kidney Foundation, or NKF, is a patient advocacy group that is focused on improving overarching care and health outcomes for people at risk for or living with chronic kidney disease across the entire spectrum of kidney disease, so going from primary prevention all the way through to improving outcomes associated with end stage renal disease, optimizing transplant care, and just overarching quality of life for people with kidney disease.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We are going to take a quick break and we will be right back to discuss the importance of early screening for chronic kidney disease or [00:20:00] CKD.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We’re back with our guests to discuss how kidney function and in the setting particularly of diabetes or hypertension can be influenced by those particular diseases. And I’m hoping, Elizabeth, you might be able to talk a little bit more about screening, which we alluded to earlier in our conversation. But what does screening for CKD involve? What do the results mean and how are we doing overall? I think you kind of told us that we’re not doing so great.

Elizabeth Montgomery (guest): Yeah, well, I would say there’s lots of opportunity for improvement around screening for chronic kidney disease. So CKD testing basics. There are two widely available, inexpensive, well characterized tests for CKD. The first is serum creatinine with eGFR, which is part of the basic metabolic and comprehensive metabolic [00:21:00] panel that everyone gets when they go to the clinician when they sneeze. The second is urine albumin creatinine ratio, which is a urine test that maybe only 20% of people who are at risk for chronic kidney disease actually receive on an annual basis.

Serum creatinine with eGFR essentially assesses for overarching kidney function, how well the kidney is actually working. uACR is associated with kidney damage. So what you will find, and what I find interesting about these two tests that are used for screening is that many people, particularly those individuals with diabetes, will have evidence of albuminuria before their serum creatinine with eGFR begins to decline. So this [00:22:00] underscores the real importance of closing the testing gap.

The second thing that I think it’s important to call out is that everyone already has serum creatinine with eGFR in their electronic health record. Like I mentioned earlier, this test is part of the basic or comprehensive metabolic panels. It’s one of the most frequently ordered tests in the United States, so anyone with access to electronic health record data has the information in the electronic health record right now that would allow them to go in and essentially characterize an entire patient population with regard to existing chronic kidney disease to help with the stratification of how to do care coordination.

And the National Kidney Foundation has several models that we can bring into a conversation with any organization that’s interested in getting an understanding [00:23:00] of how well they’re doing with testing what existing eGFR data says about their risk profiles, and then various strategies to close the testing gaps that we know exist around urine albumin creatinine ratio.

The NKF is supporting a number of pilots right now, looking at home testing to again create an opportunity to accelerate the identification of those individuals that are at greatest risk for some sort of cardiovascular event associated with their kidney disease that may not already be recognized in the electronic health record.

And it’s certainly an approach that we would recommend to any team that’s interested in really getting an understanding of how underlying chronic kidney disease may be negatively affecting both diabetes and hypertension [00:24:00] outcomes in the patient populations they’re supporting. There will be a paper that is currently available as a preprint on ResearchGate that the National Kidney Foundation submitted in partnership with an organization called Project Santa Fe, which is a group of laboratory leaders focused on laboratory driven population health.

And the NKF partnered with the Project Santa Fe team to do an analysis of the relationship between the breakdowns in chronic kidney disease testing and diagnosis and risk stratification at the population level, risk adjustment. So this paper looked at the laboratory evidence of chronic kidney disease in a laboratory information system.

It compared it to [00:25:00] the levels of chronic kidney disease diagnosis in the electronic health record and then compared those two databases with claims data to ascertain what percentage of those individuals with diabetes and CKD in its early stages were appropriately HCC coded had appropriate risk adjustment.

The outcome of this analysis and large integrated systems like Northwell, Geisinger and University of Vermont, is that shocker?… Most people are not diagnosed upstream and in the absence of diagnosis, there is no HCC code leaving about a million dollars a year on the table at each of those institutions just associated with risk adjustment for appropriate diagnosis of CKD stage three. [00:26:00] So there is a lot of opportunity for entities, individual teams that are looking to build the justification for a kidney disease quality improvement activity in their institution to build an argument to say that this investment of time and resources will pay for itself by ensuring that the populations that are being supported in value-based contracts are appropriately risk scored.

Geralyn Warfield (host): So this diagnosis that we’re talking about happening at both the system level and also the individual level is sometimes, particularly at that individual level, fraught with some difficulties. I can only imagine what it’s like for a patient to receive that stage three diagnosis, and I’m wondering if there’s some strategies that you might suggest that can help us sensitively address these kinds of diagnostics [00:27:00] with patients to move them along the continuum towards better health.

Andrew Bzowyckyj (guest): One of the things we hear very frequently from the patient side is, and actually from the providers that we work with that say, you know, the patients get concerned because all of a sudden, CKD stage three is where most patients enter into this official diagnosis. Stage three A, stage three B. The way the CKD staging occurs, you know, stage one and stage two are more glomerular damage. Its when the GFR reaches below 60 where you get into stage three where more people are identified.

However, as we’ve alluded to earlier, with that albuminuria screening, you know, hopefully we catch people even sooner than that. But instantly the other major other disease state I think that most people equate with staging is cancer. And with cancer, they’re all different but stage three tends to be very aggressive. And so then all of a sudden it’s this concern, it’s this kind of, what is happening? Like how could [00:28:00] I not have known, like what’s going on? So, I do think there’s a few things happening and one is really trying to get your elevator pitch down, so to speak, for the five stages of CKD and kind of how that works and where people land. And so whether it be helpful, you know, infographics or kind of showing, we talk about percentage of kidney function as a GFR, as more or less kind of a scale of a hundred percent can be helpful to correlate there.

Some of the other pieces is to have the conversation. I think many people are concerned, either because it’s not a primary focus or because there’s a perception that, you know, I’ve still got time, right? So, kidney decline happens over the long term, and so I’ll handle that at the next appointment. Next thing you know, it’s been 10 years. But as patients have more access to their medical data, patients have full access to the notes and different things. They’re, they’re looking and, and they’re finding this information, which also creates more shock and concern and [00:29:00] unnecessary worry.

So trying to get ahead of that, so to speak, can also be really helpful, as difficult as that conversation may be. And it’s really just relaying that information to the patient within the clinical context that you’re able to provide as a clinician.

Elizabeth Montgomery (guest): And I would add to what, what Andrew has to say by stating that at the moment, only 10% of people with kidney disease are aware that they have it, and that includes only 50% of people whose kidneys have already failed. We have an obligation to do better, and obviously that will start with testing and diagnosis in the electronic health record. And then an understanding that no one conversation is going to be the conversation that’s going to put people at ease or give them all the information that they need because the human brain, you know, defaults to third grade decision making when you’re handed this kind of [00:30:00] diagnosis. So the National Kidney Foundation is here to help with that. We have voluminous resources on our website that will help people find their way, answer questions. We are launching a patient journey branch logic learning system in the next couple of weeks that will carry people through the information they need to know.

Because chronic kidney disease is a progressive disorder, it changes over time. So instead of worrying about am I giving you the right information, pointing people in the direction of the resources that can support them on their journey is how we look at the best possible way is A, let them know that this is an issue for them and then point them in the direction of resources that they can go back to when they’ve had an opportunity to kind of process their way through what this means and position themselves to move into the self-management that can [00:31:00] actually have a net positive impact on the progression of CKD.

Geralyn Warfield (host): So there’s a lot of information that patients are getting from the healthcare professionals in with which they’re interacting. It could be a pharmacist, it could be the individual in the office, it could be something they look up online, all those things.

How do you help patients actually weigh what’s important? All these things that they’re getting in terms of polypharmacy and all the things that, you know, they have a lot going on. And after you address that for us, Andrew, I’m going to have Elizabeth talk a little bit about what we can do as clinicians or in whatever role we have to help our patients.

So Andrew, if you could start us off thinking about how to help our patients know more about what’s going on with their health.

Andrew Bzowyckyj (guest): So one of the most important things that I think patients need is just access to information, whether it be from you, the clinicians, or whether it be, you know, from online and hopefully you’re helping them navigate, you know, what’s more reliable information versus other, [00:32:00] because like it or not, patients are getting a lot of information from online and so we need to help them find that information.

One thing that a lot of the folks that are listening in the heart failure world can, can speak to or are familiar with is, you know, patient comes in, gets a brand-new diagnosis for heart failure, next thing you know, they’re on four or five new medications because that’s the guideline directed treatment. And that can be overwhelming for patients. I’ve spent some time in heart failure practice and worked with those patients. And it’d be funny, not really funny, but there’d be situations where patients, you know, they start these five new medicines, you know, they’re all for heart failure. Well, I’ll just pick this one. You know, they’re all doing the same thing, and so I’ll pick one. It was the cheapest or it was once a day. All the others were twice a day. I’ve seen that with antiplatelets and anticoagulants, all of those as well. Why do I need three? You know, I’ll just go with one. And so sometimes we run the risk of oversimplifying for patients by trying to be helpful.

We actually unintentionally kind of hurt ourselves and the patient by [00:33:00] conveying, you know, too surface level information. So, could just be the pharmacist than me, but I always kinda wanna go a little bit deeper than surface level to try to speak a little bit more to the specifics. So bringing it into the CKD space, these SGLT2 inhibitors, the non-steroidal MRAs, the GLP1 receptor agonists, all of these agents have multiple effects. And so really kind of conveying that benefit to the patient, not in an overwhelming way, but to present that information as to how holistically these are helping in multiple areas can help patients kind of be, make better, more informed decisions about their care in the treatments that they, they wish to pursue or maybe they don’t want to. And that leads a whole other conversation as to, again, risks and benefits.

Geralyn Warfield (host): So, Elizabeth, from a clinician or a healthcare professional perspective, what can we do even better?

Elizabeth Montgomery (guest): So the first thing that the National Kidney Foundation suggests is to look at your own data.

[00:34:00] So if you go to the National Kidney Foundation website, you search for CKD Intercect, you will find a link for the CKD change package. And in the CKD change package, you will, it is essentially a compendium of quality improvement activities around chronic kidney disease and you will find a data tool that can help guide your quality team through an assessment of the rates of chronic kidney disease testing in your institution, the percentage of people who actually have a diagnosis, and if you have a great quality team, what that looks like in terms of clinical care. So we suggest that you start there. That taking a look at what’s going on in your own practice and, and the unmanaged risk that your organization is bearing as a result [00:35:00] of breakdowns in chronic kidney disease is a great place to start the conversation and build the organizational will to actually intervene and close some of those gaps.

Geralyn Warfield (host): We have had an exceptional conversation thus far. I’m going to ask you each one final question, which is, what would be one key takeaway from our conversation today that you would like our listeners to leave knowing?

Andrew Bzowyckyj (guest): I can kick us off, but I will admit I have two. But they’re shorter. So thinking through, first of all, the emphasis, the importance of the urine albumin creatinine ratio, I think cannot be overstated. Thinking myself as a practitioner, you know, 10 years prior, within primarily most of the folks I saw had diabetes.

And so that, for me was a, a no-brainer, but thinking through, how many folks we see or I saw with high blood pressure and not diabetes. How many folks with cardiovascular disease or heart failure, you know, all of those are [00:36:00] also, high risk situations for CKD. So catching that uACR, it’s not a diabetes specific thing.

And I think we’ve done so much work to try to, to emphasize that screening for folks with diabetes that we forget there’s many other, you know, high risk situations for CKD that could equally benefit from at least screening with that uACR in following up.

The second thing, I hate to be that clinician that comes in and says, you need to do this and this and this and this… We realize time is of the essence. So you’ve got a 10-minute encounter, or you’ve got whatever time you have with that patient to discuss how many different things. And so always remember that one provider cannot do it all. And so whether you’re leveraging the diabetes care and education specialist, advanced practice providers, clinical pharmacists, nurse educators, whoever it may be, you know, it does take the team to truly deliver this care. And I think that’s always important. As listeners, we’re thinking, oh gosh, you want me to do what now? But remember, it’s more than one person. We need to leverage our teams [00:37:00] appropriately.

Elizabeth Montgomery (guest): And I will add to Andrew’s comments again with two. The first is a topic we really did discuss at length in this conversation, but I think it’s very important to keep in the forefront of all of our discussions around kidney disease and that this is a disease of significant disparities, communities of color are disproportionately affected by chronic kidney disease and have worse outcomes when you consider their journey and that there are significant disparities in care that evolve as chronic kidney disease progresses.

So if we are really talking about being vested in ensuring that the care that we provide is equitable we need to keep that on our lens and consider how chronic kidney disease as a quality improvement project can be aligned in a lot of other [00:38:00] ways within organizations that are looking to ensure that care is equitable across the entire spectrum. I mean, there are organizations that we’re working with that are using kidney disease related projects as the framework for their joint commission certification on health equity.

The second thing, again, just to underscore what Andrew said is that testing really matters. It really matters and that, you know, there’s data out there that suggests that the evidence of albuminuria testing in electronic health record increases the odds of someone being on basic kidney disease care, so ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptive blockers by a factor of 2.4. The odds of being on an SGLT2 inhibitor increase eight-fold if there’s uACR testing in the electronic health record, and there’s [00:39:00] even a bump that illustrates that individuals that have uACR testing in their electronic health record have overarching better blood pressure control. So the evidence suggests that this is not a conversation just to test for the sake of testing, that there is evidence that supports that the testing is efficacious, it is cost effective, and that it changes care.

And so we hope, I hope, that that would be the message that the individuals listening to this podcast would consider, is that this widely available inexpensive tests can really have a profound impact on the health outcomes for the populations they support. As well as have an impact on the overarching cost of care for the institution.

Geralyn Warfield (host): Well, speaking of profound impacts the two of you have given us so much great information today [00:40:00] that we can apply into clinical practice or whatever our role is, even starting today. And thank you so much for taking time with us. We’d also like to thank our sponsor for this particular episode, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.

And you can, as I said earlier, find links to the resources and studies and things that we’ve mentioned during the course of this episode in the show notes. This is your host, Geralyn Warfield, and we will see you next time.

Thank you for listening to Heart to Heart Nurses. We invite you to visit pcna.net for clinical resources, continuing education, and much more.

Topics

- Kidney Disease

Published on

August 20, 2024

Listen on:

PharmD, BCPS, CDCES

Related Resources