Cardiovascular Risk in Older Adults

The aging population is growing at an unprecedented rate, with more than 16.8% of the U.S individuals now over the age of 65. According to the American Heart Association (AHA), approximately 50% of U.S. adults are living with some form of cardiovascular disease (CVD), including hypertension, stroke, and heart failure, making it a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. 1-3 Older adults have a higher risk for CVD, as more than 25% of adults (aged 65- 80) have diabetes and 50% of the aging population have pre-diabetes. Other risk factors include hypertension, with a prevalence of above 70% among men and women ≥ 70 years old living in high-income countries, respectively.3 While biological aging itself contributes to increased cardiovascular risk, through processes like atherosclerosis, arterial stiffening, and endothelial dysfunction, there are also hidden triggers that accelerate heart disease risk in older adults. 2, 4

Beyond genetics and aging-related changes, lifestyle factors such as co-morbid conditions, physical inactivity, and poor cardiovascular health habits play a crucial role.2, 5 The American Heart Association’s Life’s Essential 8 emphasizes the importance of key health behaviors like following a healthy diet, exercise, sleep, and stress management in preventing CVD.2, 5 However, many older adults continue to face barriers to maintaining optimal heart health, including mobility limitations, low socioeconomic status, and social isolation.2, 6-8

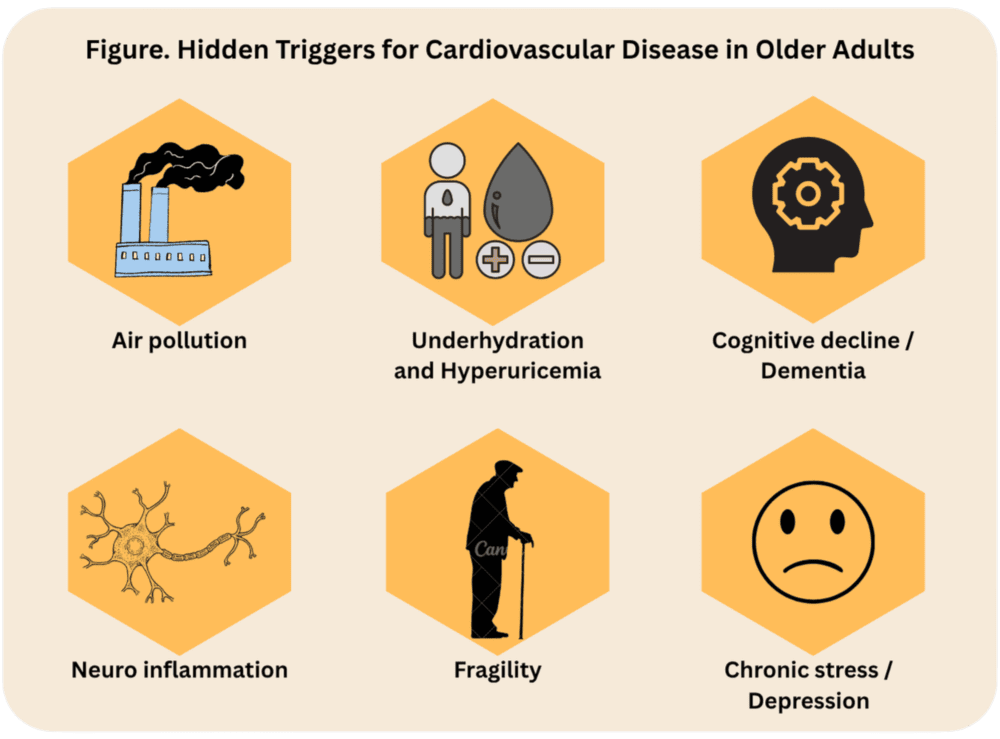

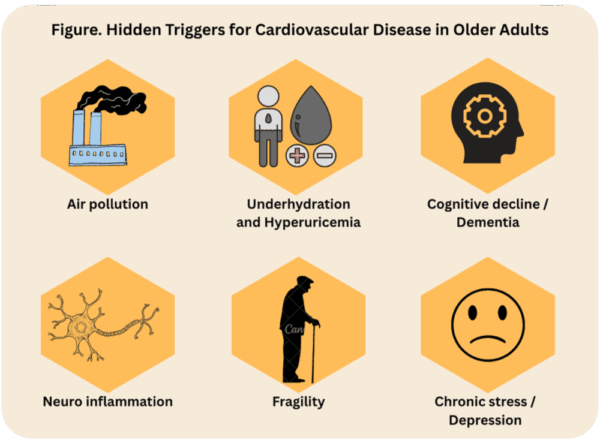

It is equally important for cardiovascular nurses to consider the social determinants of health that influence these cardiovascular risks. Addressing social determinants is vital for enhancing heart health and overall well-being among older adults.8 Key factors include economic stability, access to quality healthcare and education, and the broader social and community context, beyond environmental factors like air pollution. These determinants significantly impact both overall health and specifically CVD outcomes. Additionally, underrecognized risk factors identified through research include exposure to air pollution, cognitive impairment, hyperuricemia, depression, and frailty as ‘hidden triggers’ of CVD in aging populations (See Figure).

Uncovering Hidden Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Older Adults

It is important to recognize the social determinants that health that influence the hidden triggers of CVD, such as the neighborhood and lived environment, in which air pollution is more prevalent in those living in low-income, urban settings.8 Air pollution is scientifically linked with frailty, increased neuro-inflammation, reductions in white matter volume and ultimately cognitive decline or dementia.3, 8 This correlation contributes to the alarming high prevalence of heart failure among older adults, especially in those who are experiencing cognitive impairment.

Emerging research also highlights how chronic stress, systemic inflammation, and even gut microbiome imbalances contribute to worsening cardiovascular outcomes.3, 4, 10 As the inflammatory status of individuals increase, the risk for developing CVD also increases, underscoring the need to reduce the intake of inflammatory-provoking substances such as alcohol and tobacco.3

Evidence suggests a connection between underhydration (i.e., intake of water and fluid below recommendations) and higher serum uric acid levels (i.e., hyperuricemia) as one of the key contributors to the development and progression of CVD. Older adults often have a reduced sense of thirst and may not get enough hydration as needed. Underhydration can lead to thicker blood, increased heart rate, electrolyte imbalances, hyperuricemia with increased risk of arrhythmias or heart failure.11 Older individuals with hyperuricemia show increased prevalence of obesity, hypertension, lipid profile abnormalities, and impaired glucose metabolism, increasing their risks for developing CVD.3, 12 Furthermore, dietary intake rich in purines, primarily from meat, correlates with higher uric acid levels, whereas consuming vegetables has a protective effect. Older adults may also have reduced renal function (due to age-related decline) and may already have comorbidities like chronic kidney disease that can exacerbate the effects of thiazide diuretics such as electrolyte imbalance, (e.g., hypokalemia, hyponatremia), dehydration, hypotension, and an increased risk of acute kidney injury.12, 13

Research supports the adherence of the Mediterranean Diet to reduce the risk of hyperuricemia, inflammation, frailty, and overall, all CVD risk.2, 10, 12, 13 Understanding these factors allows healthcare professionals, particularly cardiovascular nurses and advanced practice registered nurses, to take a more proactive approach in managing heart health among older adults. Their role extends beyond clinical interventions to education, prevention, and holistic care strategies that improve long-term outcomes.2, 10

Clinical Implications: Managing Cardiovascular Risk in the Aging Population

As cardiovascular risks in aging adults continue to rise, addressing both traditional and hidden contributors to heart disease is essential. By integrating technology, patient-centered care, and lifestyle-based interventions, we can help older adults maintain healthier hearts for years to come.2, 5 Furthermore, cardiovascular nurses can tailor interventions based on the unique needs of this population, starting with examining those hidden triggers to developing CVD that remain understudied in the research. Further investigations should be focused on those lesser-known risk factors, beyond maintaining the Life’s Essential 8 preventive methods, cardiovascular nurses can leverage resources to examine the social determinants of health that influence those atypical risks for CVD among aging populations. 2, 3, 5, 8, 14

Related Articles

References

- Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CA, Arora P, Avery CL, Baker-Smith CM, Barone Gibbs B, Beaton AZ, Boehme AK. 2024 heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347-e913.

- Kumar M, Orkaby A, Tighe C, Villareal DT, Billingsley H, Nanna MG, Kwak MJ, Rohant N, Patel S, Goyal P, Hummel S, Al-Malouf C, Kolimas A, Krishnaswami A, Rich MW, Kirkpatrick J, Damluji AA, Kuchel GA, Forman DE, Alexander KP. Life’s Essential 8: Optimizing Health in Older Adults. JACC Adv. 2023;2(7). Epub 20230823. doi: 10.1016/j.jacadv.2023.100560. PubMed PMID: 37664644; PMCID: PMC10470487.

- Díez-Villanueva P, Jiménez-Méndez C, Bonanad C, García-Blas S, Pérez-Rivera Á, Allo G, García-Pardo H, Formiga F, Camafort M, Martínez-Sellés M, Ariza-Solé A, Ayesta A. Risk Factors and Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly. RCM. 2022;23(6). doi: 10.31083/j.rcm2306188.

- Nesci A, Carnuccio C, Ruggieri V, D’Alessandro A, Di Giorgio A, Santoro L, Gasbarrini A, Santoliquido A, Ponziani FR. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence on the Metabolic and Inflammatory Background of a Complex Relationship. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(10). Epub 20230522. doi: 10.3390/ijms24109087. PubMed PMID: 37240434; PMCID: PMC10219307.

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CAM, Black T, Brewer LC, Foraker RE, Grandner MA, Lavretsky H, Perak AM, Sharma G, Rosamond W, American Heart Association. Life’s Essential 8: Updating and Enhancing the American Heart Association’s Construct of Cardiovascular Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;146(5):e18-e43. doi: doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001078.

- Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, Blair IV, Cohen MS, Cruz-Flores S, Davey-Smith G, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Lauer MS, Lockwood DW, Rosal M, Yancy CW. Social Determinants of Risk and Outcomes for Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(9):873-98. Epub 20150803. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000228. PubMed PMID: 26240271.

- Bansal S, Mahendiratta S, Kumar S, Sarma P, Prakash A, Medhi B. Collaborative research in modern era: Need and challenges. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51(3):137-9. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_394_19. PubMed PMID: 31391680; PMCID: PMC6644188.

- Powell-Wiley TM, Baumer Y, Baah FO, Baez AS, Farmer N, Mahlobo CT, Pita MA, Potharaju KA, Tamura K, Wallen GR. Social Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation Research. 2022;130(5):782-99. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319811.

- Carnethon MR, Johnson DA. Sleep and resistant hypertension. Current hypertension reports. 2019;21:1-6.

- Papadopoulos PD, Tsigalou C, Valsamaki PN, Konstantinidis TG, Voidarou C, Bezirtzoglou E. The Emerging Role of the Gut Microbiome in Cardiovascular Disease: Current Knowledge and Perspectives. Biomedicines. 2022;10(5). Epub 20220420. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10050948. PubMed PMID: 35625685; PMCID: PMC9139035.

- Johnson RJ, García-Arroyo FE, Gonzaga-Sánchez G, Vélez-Orozco KA, Álvarez-Álvarez YQ, Aparicio-Trejo OE, Tapia E, Osorio-Alonso H, Andrés-Hernando A, Nakagawa T. Current hydration habits: the disregarded factor for the development of renal and cardiometabolic diseases. Nutrients. 2022;14(10):2070.

- Raja R, Kavita F, Amreek F, Shah A, Sayeed KA, Sehar A. Hyperuricemia Associated with Thiazide Diuretics in Hypertensive Adults. Cureus. 2019;11(8):e5457. Epub 20190822. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5457. PubMed PMID: 31641556; PMCID: PMC6802803.

- Chou Y-H, Chen Y-M. Aging and Renal Disease: Old Questions for New Challenges. Aging and disease. 2021;12(2):515-28. doi: 10.14336/ad.2020.0703.

- Elkind MSV, Arnett DK, Benjamin IJ, Eckel RH, Grant AO, Houser SR, Jacobs AK, Jones DW, Robertson RM, Sacco RL. The American Heart Association at 100: a century of scientific progress and the future of cardiovascular science: a Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(12):e964-e85.

Published on

July 16, 2025

DNP, APRN, ANP-BC, FNP-BC

DNP, RN, CNE, FPCNA, FAAN

PhD, MGS, RN

Related Resources

Sorry, we couldn't find any resources.