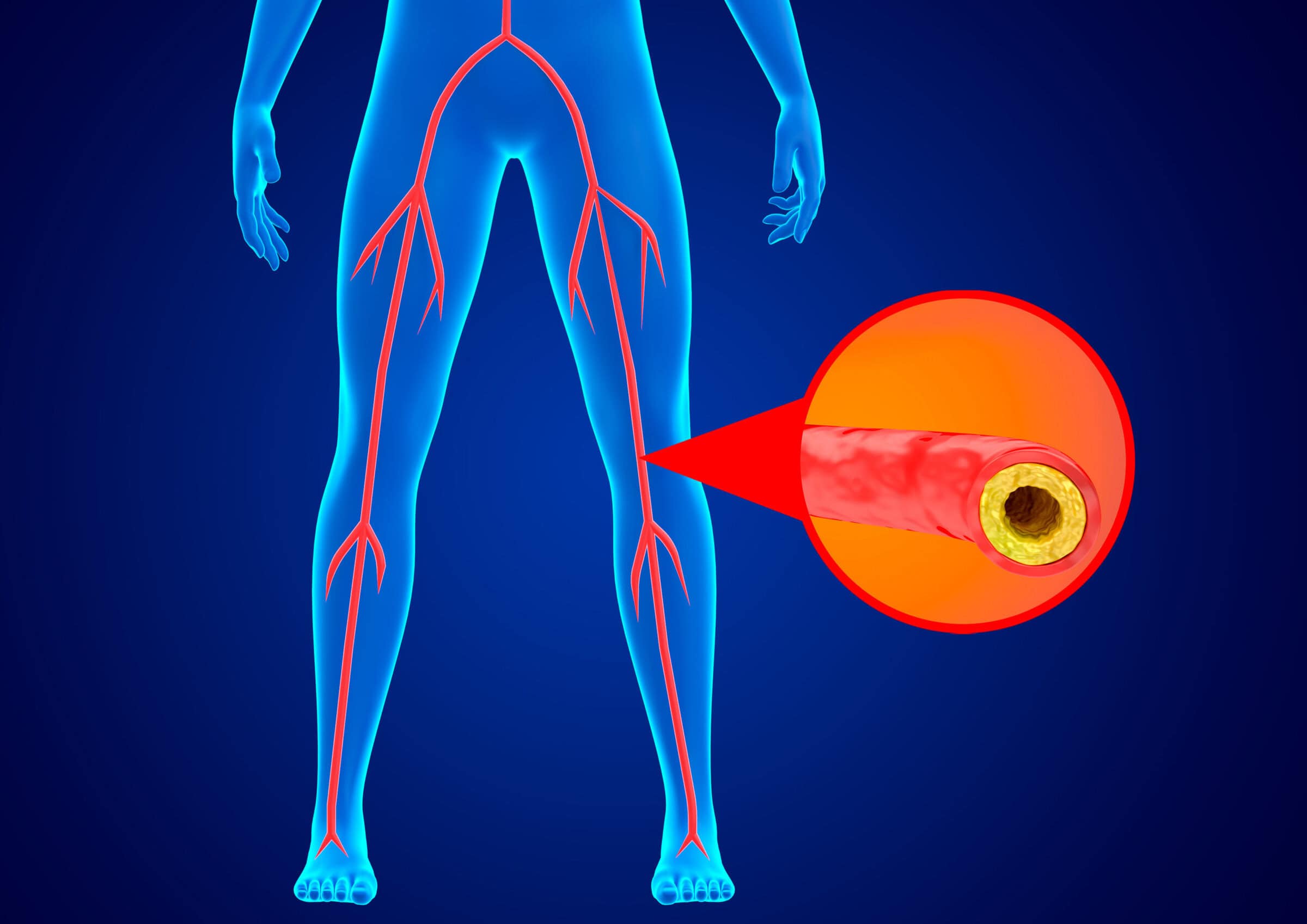

Atherosclerotic lower extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD) is being increasingly recognized as an important cause of cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality worldwide. It affects an estimated 230 million individuals worldwide and 10-12 million US adults who are over the age of 40.1 As the disease is age-related, and the global population continues to grow older, PAD prevalence is expected to continue to increase.3

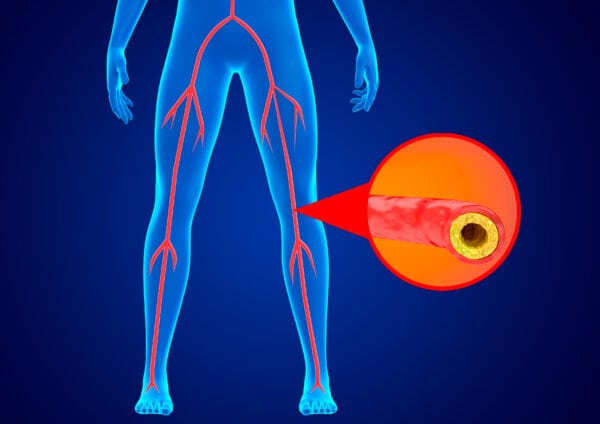

PAD is caused by narrowed arteries restricting blood flow to the limbs and is associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, amputation, and death. It also impacts quality of life, walking performance, and functional status. 2

Patients with PAD may be asymptomatic, so it is important to address risk assessment even before the development of symptoms. Early risk identification and implementation of effective management strategies may reduce disease progression and lead to improved patient outcomes.

Clinical Presentation of PAD

There are four clinical subsets of the disease. Patients may develop different symptoms over time and may move in and out of these categories.2 For example, PAD symptoms may improve with treatment or, conversely, may progress, such as the transition of PAD to chronic limb-threatening ischemia.

- Asymptomatic PAD – These individuals may self-limit and (knowingly or unknowingly) adapt their activities to reduce any associated pain. They are still at risk for MAC, including mortality.

- Chronic symptomatic PAD – Most common subset, as patients report exertional leg symptoms or claudication, which typically resolve after a short rest4

- Chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) – Severe condition: extreme pain at rest (ischemic rest pain, or neuropathic pain), wounds that heal poorly, and risk of amputation.5

- Acute limb ischemia (ALI) – Sudden decrease in arterial perfusion puts limb(s) at risk

Assessing for PAD

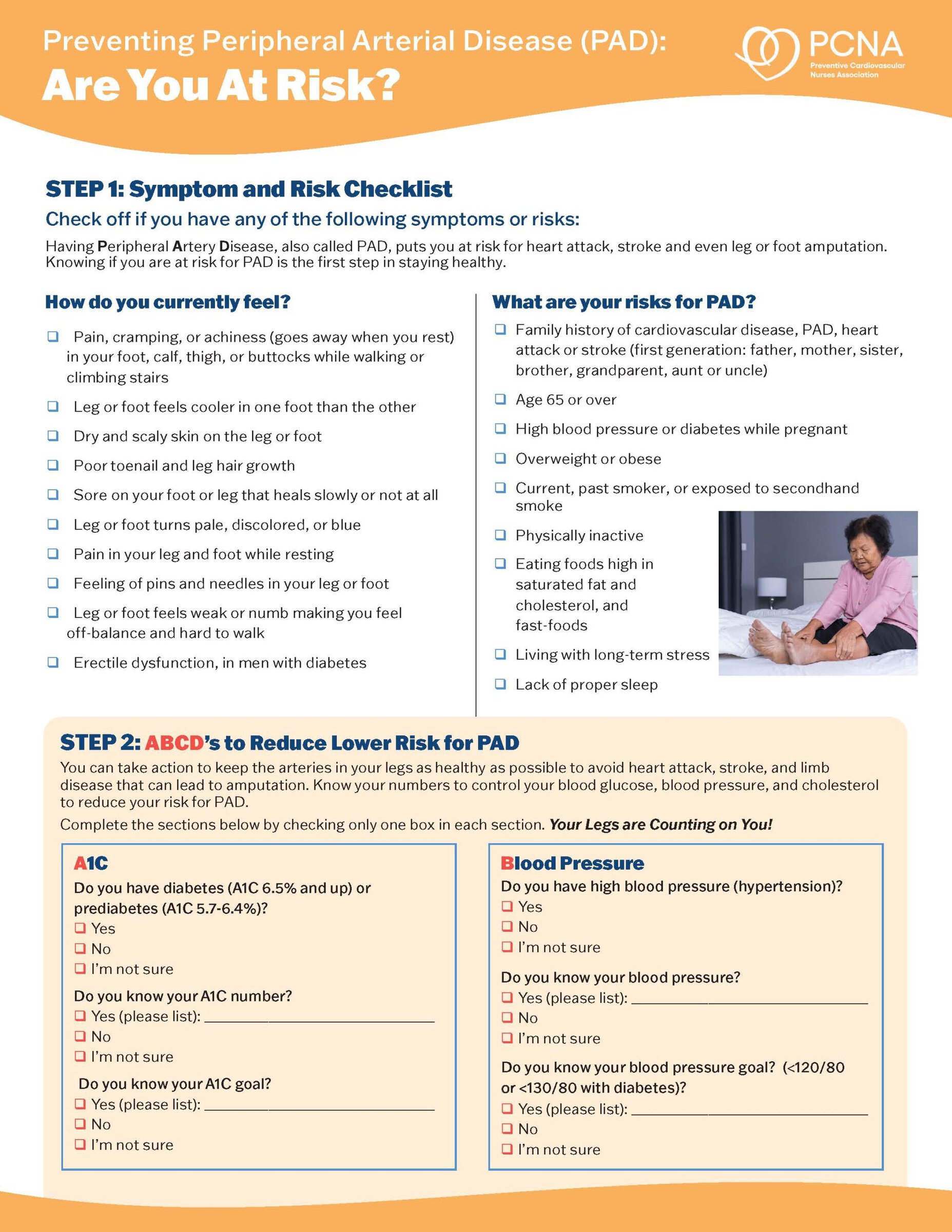

Patients at increased risk for PAD:

- Age ≥65

- Age 50-6,4 with risk factors for atherosclerosis (e.g., diabetes, history of smoking, dyslipidemia, hypertension), chronic kidney disease, or family history of PAD6

- Age <50, with diabetes and 1 additional risk factor for atherosclerosis

- People with known atherosclerotic disease in another vascular bed (e.g., coronary, carotid, subclavian, renal, mesenteric artery stenosis, or abdominal aortic aneurism)

Risk amplifiers for PAD:

- Age ≥75

- Diabetes

- Ongoing smoking/tobacco use

- Chronic kidney disease

- End-stage kidney disease (i.e., dialysis-dependent)

- Polyvascular disease

- Microvascular disease

- Depression

Disparities in the detection, management, and outcomes of PAD have a long history in the US.2 It is important to recognize that individuals who are Black are at increased risk for PAD, major adverse cardiovascular events, and major adverse cardiovascular events. The impacts of these factors, and social determinants of health on health outcomes, that contribute to a 4-fold risk of major limb amputation for Black Americans compared to their non-Hispanic White neighbors. For Black patients, these factors also contribute to worsening rates of revascularization for CLTI.7

Additionally, the estimated burden for women >40 years of age is greater than that of men who are >70 years.8 Women with PAD tend to present with more atypical leg symptoms, when they are older, and with more advanced disease.9 At similar ABI values, women have poor functional status and greater ambulatory limitations than men.10 There are also differences in types of procedures that women receive, from revascularization to amputation.

For those at increased risk, a thorough history and physical exam vascular examination are recommended. Tests such as ABI, treadmill test, angiography, and others, can help rule out other issues that may be causing the pain, such as arthritis, nerve compression, or spinal stenosis.

PAD: Head to Toe Impacts

One of the key hallmarks of PAD is pain upon walking, or claudication. The 2025 AHA Statement on the Pain Experience for patients with PAD11 supports a holistic view of the disease, where the focus is on “individual” person-centered care rather than a focus on the “limb.” Understanding the broader patient experience with PAD, as well as the psychological frameworks of illness, may help clinicians in any role on the PAD care team help drive effective management from head to toe.12,13,14

Pain is not just in your head. It is a normal adaptive response and there is a difference in pain perception from one individual to another. Early evidence suggests that most people with PAD have been experiencing symptoms between 6-12 months, which meets the definition of chronic pain.11 However, this pain is frequently treated as episodic rather than chronic, with interventions focused on ischemia relief alone.

For patients with PAD, chronic pain is an experience that exceeds the ischemia pain and is affected by a wide range of factors.11 There may also be postsurgical or posttraumatic pain, and chronic neuropathic pain.

Using a multi-modal strategy for addressing pain may be most effective. Sharing with patients information about pain management—that, for example, avoiding painful movement can be adaptive in with acute pain but may have negative effects in chronic pain—can be complemented by strategies such as lifestyle modification,2 supervised exercise training, emotion regulation, and physiologic self-regulation.16

While initially it seems counterintuitive, the use of exercise therapy to improve pain-free walking distance helps to address the chronic pain of PAD. It helps reduce inflammation, improves cardiac fitness, spurs angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels), and improves mitochondrial function—complementing the 5-30% improvements in pain that can be attributed to hemodynamic measurements.11

Additional strategies, such as the use of cognitive behavioral therapy, may also help patients with PAD better address their pain.

The Role of Cardiovascular Healthcare Professionals

Chronic diseases affect the entire body, yet the focus of healthcare professionals—and patients—sometimes becomes narrowed to just one aspect of the disease. If unaddressed, this may put the patient at risk for further issues.

The presence of PAD increases the risk of severe complications, and significantly impairs quality of life, including walking performance and chronic pain. Regardless of symptomology, diagnosis and effective management are critical to avoid a worse prognosis, reduced limb function, and even amputation.

PAD diagnosis may be difficult, particularly when additional comorbidities are present, such as spinal stenosis, osteoarthritis, diabetes, and other chronic diseases. Detection is typically done through patient history, physical exam, and resting ankle-brachial index (ABI).

Both early-stage PAD and CLTI are associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke.11 Early recognition and effective management are key to improving patient outcomes.

PAD Resources

- Recent research on thrombosis, inflammation, dyslipidemia, and microvascular disease.

- The 2024 guideline for PAD and 2025 AHA Statement on the Pain Experience for patients with PAD includes detailed resources and tools that may be used in assessing and managing pain in patients with PAD.

- For clinicians interested in providing community screening for PAD, PCNA’s screening toolkit provides a step-by-step guide for planning and implementing these activities.

References

- Aday AW, Matsushita K. Epidemiology of Peripheral Artery Disease and Polyvascular Disease. Circulation Research. 2021;128:12.

- Gornik H, Aronow HD, Googney PP, et al. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/VESS Guideline for the Management of Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149:24. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001251

- Horváth L, Németh N, Fehér G, et al. Epidemiology of Peripheral Artery Disease: Narrative Review. Life (Basel). 2022 Jul 12;12(7):1041. doi: 10.3390/life12071041

- Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e726–e779. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000471

- Smolderen KG, Ujueta F, Buckley Behan D, et al. Understanding the Pain Experience and Treatment Considerations Along the Spectrum of Peripheral Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2025;18:3.

- Wassel CL, Loomba R, Ix JH, et al. Family history of peripheral artery disease is associated with prevalence and severity of peripheral artery disease: the San Diego population study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1386–1392.

- Creager MA, Matsushita K, Arya S, et al. Reducing nontraumatic lower-extremity amputations by 20% by 2030: time to get to our feet: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e875–e891.

- Hirsch AT, Allison MA, Gomes AS, et al. A call to action: women and peripheral artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:1449–1472.

- Pabon M, Cheng S, Altin SE, et al. Sex differences in peripheral artery disease. Circ Res. 2022;130:496–511.

- McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, et al. Sex differences in peripheral arterial disease: leg symptoms and physical functioning. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:222–228.

- Smolderen KG, Ujueta F, Buckley Behan D, et al. Understanding the Pain Experience and Treatment Considerations Along the Spectrum of Peripheral Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2025;18:3. https://doi.org/10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000135

- Shean KE, Soden PA, Schermerhorn ML, et al. Lifelong limb preservation: a patient-centered description of lower extremity arterial reconstruction outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2017;66:1117–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.02.043

- Smolderen KG, Alabi O, Collins TC, et al. American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. Advancing peripheral artery disease quality of care and outcomes through patient-reported health status assessment: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;146:e286–e297. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001105

- Smolderen KG, Samaan Z, Decker C, et al. American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Association between mental health burden, clinical presentation, and outcomes in individuals with symptomatic peripheral artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;148:1511–1528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001178

- Ney B, Lanzi S, Calanca L, Mazzolai L. Multimodal supervised exercise training is effective in improving long term walking performance in patients with symptomatic lower extremity peripheral artery disease. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2057. doi: 10.3390/jcm10102057

- McKenna K, Gallagher KA, Forbes PW, Ibeziako P. Ready, set, relax: biofeedback-assisted relaxation training (BART) in a pediatric psychiatry consultation service. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2014.06.003

Published on

May 7, 2025

PhD, MPH, RN, CDCES, FAHA, FPCNA, FAAN

Related Resources